There are No Silver Bullets— Only Science to Preparation to Implementation to Evaluation to Celebration

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction: Another Study on Disproportionality—Integrating the Four Studies Published This Month

Since beginning this series—about six weeks ago—on Disproportionate School Discipline Referrals and their effects on African-American and male students, and Students with Disabilities (SWD), four different national reports in the area have been published.

While each of them is important on their own, a side-by-side integration of the four tell a compelling story about how we have been addressing this problem (largely unsuccessfully), and what we now need to do.

While Parts I and II of this Blog series analyzed three of these reports, let me review the last one and then provide the integration.

_ _ _ _ _

On May 2, 2018, the AASA—the national School Superintendents Association published its 2018 AASA School Discipline Survey. This survey included responses from 950 school leaders in 47 states, and it specifically investigated the impact of the 2014 “Dear Colleague Letter on the Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline” issued jointly by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

CLICK HERE for 2018 AASA Survey

CLICK HERE for 2014 “Dear Colleague” Letter

_ _ _ _ _

To provide an historical context: The “Dear Colleague” Letter began with the following:

The U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice (Departments) are issuing this guidance to assist public elementary and secondary schools in meeting their obligations under Federal law to administer student discipline without discriminating on the basis of race, color, or national origin. The Departments recognize the commitment and effort of educators across the United States to provide their students with an excellent education. The Departments believe that guidance on how to identify, avoid, and remedy discriminatory discipline will assist schools in providing all students with equal educational opportunities

_ _ _ _ _

The Letter went on to provide an extensive description of the characteristics of effective school discipline approaches that would moderate disproportionality, but it did state that:

Regardless of the program adopted, Federal law prohibits public school districts from discriminating in the administration of student discipline based on certain personal characteristics. The Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division (DOJ) is responsible for enforcing Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title IV), 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c et seq., which prohibits discrimination in public elementary and secondary schools based on race, color, or national origin, among other bases. The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and the DOJ have responsibility for enforcing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d et seq., and its implementing regulations, 34 C.F.R. Part 100, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or national origin by recipients of Federal financial assistance. Specifically, OCR enforces Title VI with respect to schools and other recipients of Federal financial assistance from the Department of Education.

The Departments initiate investigations of student discipline policies and practices at particular schools based on complaints the Departments receive from students, parents, community members, and others about possible racial discrimination in student discipline. The Departments also may initiate investigations based on public reports of racial disparities in student discipline combined with other information, or as part of their regular compliance monitoring activities

_ _ _ _ _

Given this context, the primary results of the 2018 AASA School Discipline Survey were:

Only 16% of the district leaders surveyed said their district modified their school discipline policies and practices due to Letter.

Of these 16%, 44% reported positive effects relative to their modifications, 25% reported negative effects, and 12% reported mixed effects.

_ _ _ _ _

Of the “negative effect” respondents, their biggest concerns were:

Teachers’ inability to remove aggressive students from their classrooms, which led to a meaningful loss of instructional time for other students.

A decrease in staff morale of for personnel who were unable to change students’ bad behavior or were spending considerable time in trying to manage it.

The lack of student accountability for their inappropriate behavior empowered them to misbehave since they no longer were sent home.

_ _ _ _ _

Other Results:

Urban and large districts were more likely to adopt new discipline policies and practices because of the 2014 discipline guidance.

20% of district leaders confirmed that pressure from OCR, but not necessarily the guidance itself, led them to keep students in school who school staff would have preferred to remove.

District leaders say OCR’s method of investigating individual student complaints of discipline discrimination needs to be reformed.

Finally, a previous AASA survey, completed in 2013, found that 56% of the current respondents had recently changed their discipline policies. Thus, it is possible that—as many of the respondents had already changed their policies in 2013—they did not feel the need to change their policies again (or differently) in response to the 2014 Dear Colleague guidance.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Integrating the Four Disproportionality Studies

As discussed in the first two Blog in this series, the other three disproportionality-related studies included the following:

K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities (U.S. Government Accountability Office; April 4, 2018):

[CLICK HERE for Original GAO Study]

[Reported in Blog Part I: CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _

U.S. Office of Civil Rights 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection: School Climate and Safety (U.S. Department of Education; April 24, 2018):

[CLICK HERE for the CRDC Data-base]

[CLICK HERE for the CRDC Safety Briefing Report]

_ _ _ _ _

Disabling Punishment: The Need for Remedies to the Disparate Loss of Instruction Experienced by Black Students with Disabilities (The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project and The Houston Institute for Race and Justice; April 19, 2018):

[CLICK HERE for Resource]

[Both reported in Blog Part II: CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _

Integrating these and the AASA study above, the data reflect the following results:

Based on the CRDC data from the 2013-14 school year, black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) in K-12 public schools.

These disparities were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended.

By the 2015-16 school year, the CRDC data reveal that, while U.S. schools are suspending fewer students, African-American students continue to receive disproportionately more suspensions.

26% of Students with Disabilities (SWDs) received at least one suspension during the 2015-16 school year, even though they represented only 12% of all students enrolled.

While SWDs of all races received higher rates of discipline than non-disabled students, there were significant gaps between African-American SWDs and white SWDs. Specifically, in both the 2014-15 and 2015-16 school years, African-American SWDs lost roughly three times more instructional days due to disciplinary referrals, than their white SWD peers.

The 2015-16 suspension rates reflect the same gaps, for African-American and SWDs, as five years ago.

_ _ _ _ _

Flaws and Conclusions. Critically, an analysis of the state and district policy and practice approaches being used to address disproportionate discipline referrals over the past ten years (see Blog Part I) suggests the following flaws:

Flaw #1. Legislatures (and other “leaders”) are trying to change practices through policies.

Flaw #2. State Departments of Education (and other “leaders”) are promoting one-size-fits-all programs with “scientific” foundations that do not exist or are flawed

Flaw #3. Districts and schools are implementing disproportionality “solutions” (Frameworks) that target conceptual constructs rather than teaching social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Flaw #4. Districts and Schools are not recognizing that Classroom Management and Teacher Training, Supervision, and Evaluation are Keys to Decreasing Disproportionality.

Flaw #5. Schools and Staff are trying to motivate students to change their behavior when they have not learned, mastered, or cannot apply the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed to succeed.

Flaw #6. Districts, Schools, and Staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services, supports, and interventions needed by students.

_ _ _ _ _

Given all of the discussion to date, we suggest the following conclusions:

While bias, prejudice against, and sometimes fear of African-American students and Students with Disabilities are prevalent, the primary reasons why we are not decreasing disproportionate discipline referrals relates to gaps in deep knowledge and understanding, resources and strategies, training and mentoring, and consultation and accountability.

Indeed, during the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ interactions and reactions with African-American students, boys, and students with disabilities. . . reactions that, at times, are the reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals.

And, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, the involvement of law enforcement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

Instead, on one hand, we have been tinkering around the policy edges by simply deciding that specific students will not be suspended for their inappropriate behavior—without involving teachers and other staff in these decisions, increasing staff training and capacity, or providing additional staff and other intervention resources.

And then, on the other hand, we have been tinkering around the practice edges by endorsing and implementing frameworks and programs that do not focus on social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills; that are based more on testimonials, than sound research implemented across numerous diverse settings; and that allow schools and staff to select the strategies they want to implement, rather than providing an evidence-based blueprint of essential, multi-tiered science-to-practice supports, strategies, and interventions.

In some cases, the initial discipline data suggested that state, district, and school “tinkering” succeeded. But the more comprehensive data (as in the four studies above), now tell us that the problems remain, and that other, unintended problems may have additionally resulted.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Solving the Disproportionality Dilemma: Suggestions from the 2014 "Dear Colleague" Letter

The body of the 2014 “Dear Colleague” Letter focused primarily on identifying the federal laws relevant to disproportionality and equal access, and the right of the Departments of Justice and Education to investigate districts and schools to enforce these laws. The Letter provides a flow chart showing the decision-rules that the two Departments were using to determine whether a school’s discipline policies were discriminatory, and it even presented seven case study examples of school policies that would, indeed, be considered discriminatory.

The clear intent of the Letter was to “draw a legal line in the sand”—explicitly telling districts and schools that these two federal departments both intended to respond to reported complaints about discrimination, as well as initiate their own compliance reviews in this area.

Unfortunately, given its threatening tone and intent, it is very likely that many districts and schools never got around to reading the Appendix to the Letter. This is unfortunate, because the Appendix (“Recommendations for School Districts, Administrators, Teachers, and Staff”) is actually quite good.

Indeed, it provides a sound “first layer” of strategies that could help any district or school prevent and/or address current levels of discipline-related disproportionality.

Below, are the most essential strategies as quoted from this Appendix.

I. Climate and Prevention

(A) Safe, inclusive, and positive school climates that provide students with supports such as evidence-based tiered supports and social and emotional learning.

Develop and implement a comprehensive, school- and/or district-wide approach to classroom management and student behavior grounded in evidence-based educational practices that seeks to create a safe, inclusive, and positive educational environment.

Ensure that appropriate student behavior is positively reinforced. Such reinforcement could include school-wide tiered supports, including universal, targeted, and intensive supports, to align behavioral interventions to students’ behavioral needs.

Encourage students to accept responsibility for any misbehavior and acknowledge their responsibility to follow school rules.

Assist students in developing social and emotional competencies (e.g., self-management, resilience, self-awareness, responsible decision-making) that help them redirect their energy, avoid conflict, and refocus on learning.

Refer students with complex social, emotional, or behavioral needs for psychological testing and services, health services, or other educational services, where needed.

Ensure that there are sufficient school-based counselors, social workers, nurses, psychologists, and other mental health and supportive service providers to work with students and implement tiered supports. Involve these providers in addressing disciplinary incidents; preventing future disciplinary concerns; reintegrating students who are returning from suspensions, alternative disciplinary schools, or incarceration; and maintaining a safe, inclusive, and positive educational environment.

_ _ _ _ _

(B) Training and professional development for all school personnel

Provide all school personnel, including teachers, administrators, support personnel, and school resource officers, with ongoing, job-embedded professional development and training in evidence-based techniques on classroom management, conflict resolution, and de-escalation approaches that decrease classroom disruptions and utilize exclusionary disciplinary sanctions as a last resort.

Train all school personnel on the school’s written discipline policy and how to administer discipline fairly and equitably. Facilitate discussion for all school personnel of the school’s discipline policies and the faculty’s crucial role in creating a safe, inclusive, and positive educational environment.

Provide training to all school personnel on how to apply subjective criteria in making disciplinary decisions.

Provide cultural awareness training to all school personnel, including training on working with a racially and ethnically diverse student population and on the harms of employing or failing to counter racial and ethnic stereotypes.

Establish procedures to assess the effectiveness of professional development approaches in improving school discipline practice and staff knowledge and skills.

Establish procedures for school administrators to identify teachers who may be having difficulty managing classrooms effectively, preventing discipline problems from occurring, or making appropriate disciplinary referrals, and to provide those teachers with assistance and training.

Ensure that appropriate instruction is provided to any volunteer on a school’s campus regarding the school’s approach to classroom management and student behavior.

_ _ _ _ _

II. Clear, Appropriate, and Consistent Expectations and Consequences

(A) Nondiscriminatory, fair, and age-appropriate discipline policies

Ensure that school discipline policies specifically and positively state high expectations for student behavior, promote respect for others, and make clear that engaging in harassment and violence, among other problem behaviors, is unacceptable.

Ensure that discipline policies include a range of measures that students may take to improve their behavior prior to disciplinary action.

Develop or revise written discipline policies to clearly define offense categories and base disciplinary penalties on specific and objective criteria whenever possible. If certain offense categories have progressive sanctions, clearly set forth the range of sanctions for each infraction.

Ensure that the sanctions outlined by the school’s discipline policies are proportionate to the misconduct.

Review standards for disciplinary referrals and revise policies to include clear definitions of offenses and procedures for all school personnel to follow when making referrals.

Clearly designate who has the authority to identify discipline violations and/or assign penalties for misconduct.

Ensure that the school’s written discipline policy regarding referrals to disciplinary authorities or the imposition of sanctions distinguishes between those students who have violated the school’s discipline policy for the first time and those students who repeatedly commit a particular violation of the discipline policy.

Ensure that appropriate due process procedures are in place and applied equally to all students and include a clearly explained opportunity for the student to appeal the school’s disciplinary action.

_ _ _ _ _

(B) Communicating with and engaging school communities

Involve families, students, and school personnel in the development and implementation of discipline policies or codes of conduct and communicate those policies regularly and clearly.

Provide the discipline policies and student code of conduct to students in an easily understandable, age-appropriate format that makes clear the sanctions imposed for specific offenses, and periodically advise students of what conduct is expected of them.

Put protocols in place for when parents and guardians should be notified of incidents meriting disciplinary sanctions to ensure that they are appropriately informed.

Post all discipline-related materials on district and school websites.

Provide parents and guardians with copies of all discipline policies, including the discipline code, student code of conduct, appeals process, process for re-enrollment, where appropriate, and other related notices; and ensure that these written materials accurately reflect the key elements of the disciplinary approach, including appeals, alternative dispositions, time lines, and provisions for informal hearings.

Translate all discipline policies, including the discipline code and all important documents related to individual disciplinary actions, to ensure effective communication with students, parents, and guardians who are limited English proficient. Provide interpreters or other language assistance as needed by students and parents for all discipline-related meetings, particularly for expulsion hearings.

Establish a method for soliciting student, family, and community input regarding the school’s disciplinary approach and process, which may include establishing a committee(s) on general discipline policies made up of diverse participants, including, but not limited to students, administrators, teachers, parents, and guardians; and seek input from parents, guardians, and community leaders on discipline issues, including the written discipline policy and process.

_ _ _ _ _

(C) Emphasizing positive interventions over student removal

Ensure that the school’s written discipline policy emphasizes constructive interventions over tactics or disciplinary sanctions that remove students from regular academic instruction (e.g., office referral, suspension, expulsion, alternative placement, seclusion).

Ensure that the school’s written discipline policy explicitly limits the use of out-of-school suspensions, expulsions, and alternative placements to the most severe disciplinary infractions that threaten school safety or to those circumstances where mandated by Federal or State law.

Ensure that the school’s written discipline policy provides for individual tailored intensive services and supports for students reentering the classroom following a disciplinary sanction.

Ensure that the school’s written discipline policies provide for alternatives to in-school and out-of-school suspensions and other exclusionary practices (i.e., expulsions).

_ _ _ _ _

III. Equity and Continuous Improvement

(A) Monitoring and self-evaluation

Develop a policy requiring the regular evaluation of each school’s discipline policies and practices and other school-wide behavior management approaches to determine if they are affecting students of different racial and ethnic groups equally. Such a policy could include requiring the regular review of discipline reports containing information necessary to assess whether students with different personal characteristics (e.g., race, sex, disability, and English learner status) are disproportionately disciplined, whether certain types of disciplinary offenses are more commonly referred for disciplinary sanctions(s), whether specific teachers or administrators are more likely to refer specific groups of students for disciplinary sanctions, and any other indicators that may reveal disproportionate disciplinary practices.

Establish a means for monitoring that penalties imposed are consistent with those specified in the school’s discipline code.

Conduct a periodic review of a sample of discipline referrals and outcomes to ensure consistency in assignments.

_ _ _ _ _

(B) Data collection and responsive action

Collect and use multiple forms of data, including school climate surveys, incident data, and other measures as needed, to track progress in creating and maintaining a safe, inclusive and positive educational environment.

Collect complete information surrounding all discipline incidents, including office referrals and discipline incidents that do not result in sanctions. Relevant data elements include information related to the date, time, and location of the discipline incident; the offense type; whether an incident was reported to law enforcement; demographic and other information related to the perpetrator, victim, witness, referrer, and disciplinarian; and the penalty imposed. Ensure that there are administrative staff who understand how to analyze and interpret each school’s discipline data to confirm that data are accurately collected, reported, and used.

Create and review discipline reports to detect patterns that bear further investigation, assist in prioritizing resources, and evaluate whether a school’s discipline and behavior management goals are being reached.

If disparities in the administration of student discipline are identified, commit the school to a plan of action to determine what modifications to the school’s discipline approach would help it ameliorate the root cause(s) of these disparities.

Develop a discipline incident database that provides useful, valid, reliable, and timely discipline incident data.

Provide the school board and community stakeholders, consistent with applicable privacy laws and after removing students’ identifiable information, with disaggregated discipline information to ensure transparency and facilitate community discussion.

Make statistics publicly available on the main discipline indices disaggregated by school and race.

Maintain data for a sufficient period of time to yield timely, accurate, and complete statistical calculations.

In addition to the Federal civil rights laws, ensure that the school’s discipline policies and practices comply with applicable Federal, State, and local laws, such as IDEA and FERPA.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Solving the Disproportionality Dilemma: Our Suggestions

In order to fully operationalize the strategies above, districts and schools need to drill one more level down. They need to implement additional, multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies that prevent disproportionality by focusing on the implementation of (a) an effective school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management system for all students; complemented by (b) effective data-based, functional assessment, problem-solving approaches that determine the root causes of the persistent or significantly problematic behaviors of challenging students—then linking the assessment results to strategic and/or intensive interventions.

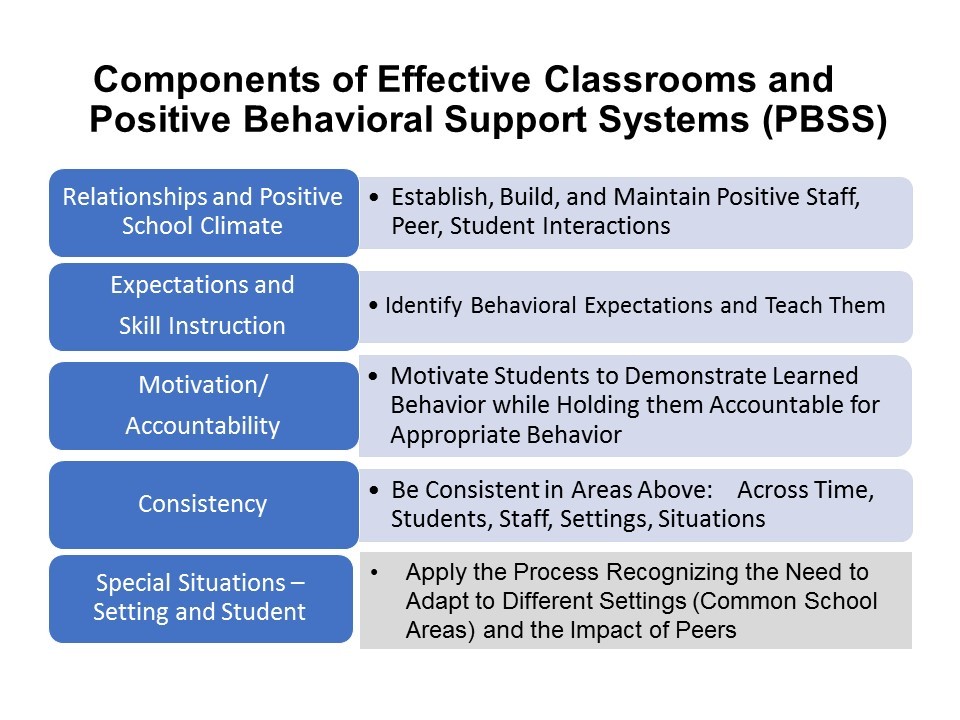

In Part II of this Blog series, we described the five science-to-practice components that interdependently organize this multi-tiered system. With an ultimate goal of having all students consistently demonstrate the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills that they need for school (and life) success, these five interdependent components are:

* Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

* Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

* Student Motivation and Accountability

* Consistency

* Implementation and Application Across All Settings and All Peer Groups

From: Knoff, H.M. (2014). School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support Implementation Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

CLICK HERE for more information.

_ _ _ _ _

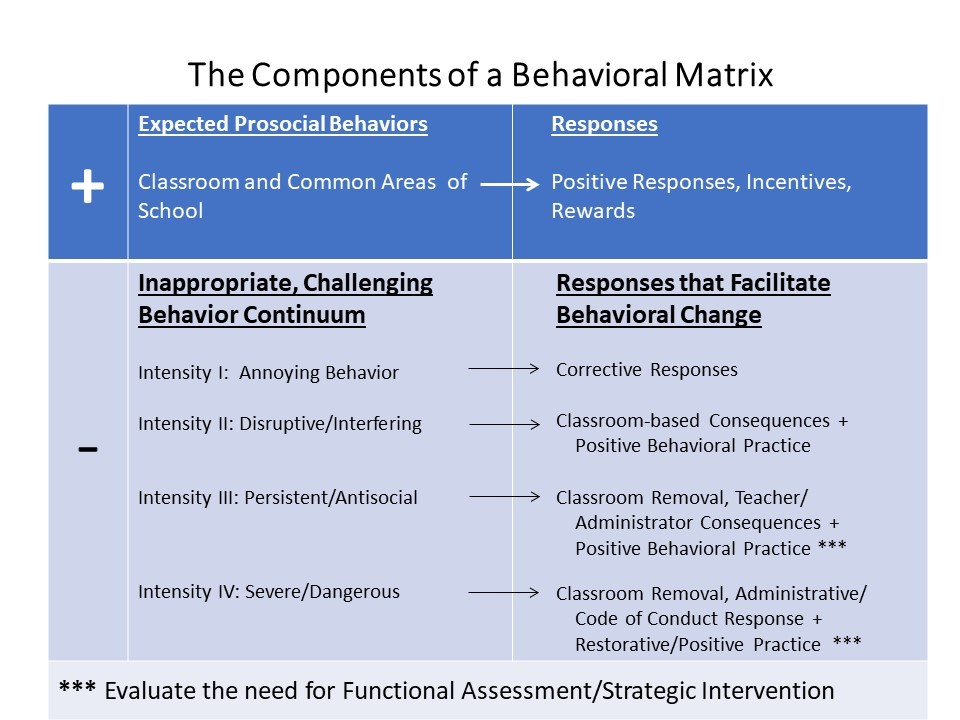

Part II went on to specifically focus on the Student Motivation and Accountability component by describing the development and use of a Behavioral Matrix—which outlines responses that help teachers, staff, and administrators motivate and reinforce appropriate student behavior, and decision-making guidelines to help staff respond to different intensity levels of inappropriate student behavior—with a goal of eliminating that behavior and replacing it with appropriate behavior (see Figure below).

When used with fidelity, the Behavioral Matrix not only changes how staff interact with their students, but it also consistently minimizes (if not eliminates) the disproportionality that occurs when teachers (and others) send African-American students and Students with Disabilities to the office for behavioral offenses that they handle in the classroom with Caucasian and other students.

The Behavioral Matrix also changes students’ behavior by increasing their self-awareness, ability to self-monitor and self-manage, and motivation to use their social and interpersonal decision-making skills. This decreases disproportionality because minority students and SWDs (a) demonstrate more appropriate prosocial behavior “the first time,” (b) correct their inappropriate classroom behavior more quickly and at a lower level of intensity when that occurs, and (c) respond to the administrative responses written into the “upper levels” of the Behavioral Matrix because they are held accountable for their behavior, or because its root causes are identified and addressed.

In this latter situation, the Behavioral Matrix process prompts staff to refer students to the school’s Student Assistance Team (or the equivalent) when disciplinary approaches are not changing student behavior. Here, a data-based functional assessment of a student’s behavior is completed to determine its social, emotional, behavioral, or situational root causes, and to identify the strategic or intensive services, supports, strategies, or interventions needed to address those causes and to change the student’s behavior.

[Read this entire discussion in Blog Part II: CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Highlighting the Importance of Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

While the Behavioral Matrix (see Figure above) clearly identifies the behavioral expectations in a school’s classrooms and across its common areas. . .

. . . if students are not behaviorally taught these expectations, then there is no reason to expect them to exhibit them.

While all students need this instruction, when the data from a school or district indicates a significant level of disproportionality, it is important to determine if the instruction needs to be modified or adapted for select minority students and/or SWDs.

For example, these students may need smaller group or modified instruction, instruction that provides more positive practice repetitions, more culturally-sensitive or culturally-relevant instruction, or instruction that includes specific accommodations to help the students learn.

The “bottom line” is that the instruction must be pedagogically sound, it must include modifications as necessary, and it must extend from preschool through high school. In addition, the classroom and building expectations must be operationalized as discrete social, emotional, and behavioral skills, and they need to be explicitly taught as discrete, observable, and measurable skills. And these skills need to reflect what we needs students to do, rather than what we want students to stop, avoid, or not do.”

Thus, it is not instructionally helpful to teach or talk to students in constructs—telling them that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each of these constructs involve a wide range of behaviors, and students may not know which behaviors are needed for what situations.

Instead, we need to teach students discrete skills—for example, how to listen, follow directions, ask for help, stay in emotional control, be aware of their feelings, agree to disagree with a peer, etc.

And, relative to the teaching process, we need to use science-to-practice methods that are grounded in social learning theory. Specifically, we need to teach students targeted social, emotional, and behavior skills by task analyzing the skills into specific steps (or scripts), demonstrating (or modeling) the steps to them, giving students opportunities to practice (role play) with explicit (performance) feedback, and then helping them to apply (or transfer) their new skills to “real-world” situations.

_ _ _ _ _

We have summarized these science-to-practice methods in a free technical assistance paper that uses The Stop & Think Social Skills Program as a prototypical example. The Stop & Think Social Skills Program is an evidence-based program through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), it is one of the most behavioral social skills programs available, and it is one of the top social skills programs available in the country.

The technical assistance paper, The Stop & Think Social Skills Program: Exploring Its Research Base and Rationale, is available here:

[For a free copy of the paper, CLICK HERE]

Briefly, the paper discusses eight scientific foundations of a sound social skills program—using examples from the Stop & Think Social Skills Program to demonstrate how to apply science into practice.

The following Principles were discussed:

Principle 1. Social skills programs teach sensible and pragmatic classroom-centered skills needed by today's students in the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping areas.

Principle 2. Social skills programs teach sensible and pragmatic classroom and common school area routines needed by today’s students to “navigate” successfully within these settings.

Principle 3. Social skills programs teach their skills in an organized and progressive, yet flexible, “scope and sequence” using research-based instructional approaches.

Principle 4. Social skills programs teach specific social skills using a universal language and specific skill scripts that guide step-by-step implementation. The instructional process facilitates the conditioning, reconditioning, and motivation of students so that they actually demonstrate prosocial choices and behaviors.

Principle 5. As previously discussed (see Principle 3), an effective social skills program results in students demonstrating specific behavioral skills—for example, how to Listen, Follow Directions, Ask for Help, Ignore Distractions, Respond to Teasing, etc. . . . as well as how to control their emotions.

Principle 6. Social skills programs teach their specific social skills using sound, scientifically-based pedagogical practices.

Principle 7. Social skills programs teach their specific skills using approaches and practices that are sensitive to students’ gender and sexual identity, socio-economic status, geographic variations, and multi-national/multi-cultural differences.

Principle 8. Social skills training, by itself, will not result in needed (or desired) school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management outcomes. Social skills training must be connected to four related components that work, systemically and interdependently, to attain these school, setting, and student outcomes.

_ _ _ _ _

These principles need to be applied to any social-emotional or social skills training program. There are a great number of programs “on the market” that the publishers or developers say are “research-based.” If our students (a) need to learn (and they do—from preschool through high school) social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills, and if these skills (b) are essential to decreasing or eliminating students’ inappropriate school and classroom behavior—which then eliminates the need for (disproportionate) discipline referrals, then (c) it is incumbent on educators, schools, and districts to ensure that they are selecting and implementing scientifically-sound programs that have the highest probability of success.

The principles above provide the evaluative “scorecard” needed for an independent, objective evaluation of any social skills program. Please read and use the free technical assistance papers. There are too many schools across the country that are implementing scientifically unsound social, emotional, and behavioral instruction approaches and then—when they are unsuccessful—they attribute students’ continuing inappropriate behavior to the students and their “resistance” to intervention. . . when the real reason for the lack of success is the selection of the program itself.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

While disproportionality is often seen as a complex issue, it is less complex when the preventative goals (i.e., self-management) are clear, when sound research-to-practice components (i.e., the five interdependent components described above) guide the multi-tiered process, when training and resources are effectively applied to the components, and when functional assessments linked to strategic or intensive interventions are used when students are not responding to a multi-layered progressive discipline blueprint (i.e., the Behavioral Matrix).

If we have learned one thing over the past ten or more years, it is that policy changes alone will not decrease the disproportionate discipline referrals of African-American, male, and disabled students.

At the same time, there are successful evidence-based approaches. It’s just that they take training, resources, commitment, consistency, and time to work.

Not that schools and districts have been avoiding these approaches. . . but where would our schools be today if they began implementing the components and strategies discussed in these three Blogs (there are others) ten years ago?

Would this have taken a “leap of faith?” Of course. . . . everything does. But the schools that have worked with us—and sustained their practices—are better off because of it.

Indeed. . . when you have the outcome data from schools that “took the leap” from across the country. . . the next leap is smaller, and the potential rewards are self-evident.

_ _ _ _ _

I appreciate your interest and attention to the thoughts that I share every few weeks. I always look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail. And I hope that I am providing enough information for you to implement some of my ideas with fidelity and success.

If I can ever help you in any of the areas discussed in this Series or other blogs, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

As we get close to Memorial Day, please accept my best wishes for a safe holiday weekend and end to your school year.

Best,

Howie