Why Schools Need to Re-Think, Re-Evaluate, Re-Load, and Re-Boot

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

All students need to learn and demonstrate—at an appropriate developmental level—effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills. In the classroom, these skills are essential to maximizing their academic engagement and achievement, as well as their ability to collaborate and learn in cooperative and project-based learning groups.

The “Good News” is that this is increasingly recognized in our educational communities.

Indeed, based on McGraw-Hill’s just-published Education 2018 Social and Emotional Learning Report with its survey of over 1,000 administrators, teachers, and parents, all three groups said that they believe that social and emotional learning is just as important as academic learning. More specifically, social and emotional learning was endorsed by 96% of administrators, 93% of teachers, and 81% of parents.

The Report also noted that:

- Nearly two-thirds of the educators surveyed said their school is in the process of implementing a school-wide strategic SEL plan.

- Three-quarters of teachers surveyed say they are teaching SEL in their classrooms, and 74% of teachers say they are devoting more time to teaching SEL today than five years ago.

- Teachers and administrators said that social and emotional learning programs would positively impact school safety (76% and 66%, respectively), lack of student motivation and engagement (75% and 66%), and school climate (71% and 69%).

- However, just 22% of the educators said that they feel “very prepared” to teach SEL, and 51% said the level of SEL professional development at their school is not sufficient.

- Among the skills that the administrators and teachers ranked as “very important” for students were: Self-management (95% and 93%), Relationship skills (93% for both groups), Responsible decision-making (92% for both groups), Self-awareness (90% for both groups), and Social awareness (88% and 89%)

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to the last bullet above, it is important to note that the cited skills are essential in school. . . but also to students’ when they enter the post-graduation workplace.

Indeed, an AACU Employer Survey & Economic Trend Research report, referenced in the September 5, 2018 issue of Education Week, identified the following top characteristics that employers seek of new hires:

- Able to effectively communicate orally

- Critical thinking/analytical reasoning

- Ethical judgment and decision-making

- Able to work effectively in teams

- Able to work independently (Prioritize and Manage Time)

- Self-motivated, shows initiative, proactive: Ideas/Solutions

- Able to communicate effectively in writing

- Can apply knowledge/skills to real-world settings

Embedded within many of these characteristics are the prosocial skills referenced above. But in order to demonstrate these characteristics and skills, they need to be explicitly taught to students. . . from preschool through high school. . . as part of a systematic, scaffolded, articulated Health, Mental Health, and Wellness “curriculum.”

And, as part of the instructional process, students need to learn, master, and be able to apply these skills in a timely way to different situations.

To accomplish all of this, students need to learn and demonstrate:

- Self-control—when experiencing emotional conditions;

- Cognitive, or attributional, control—so that their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and expectations support and motivate prosocial behavior; and the

- Verbal, non-verbal, and physical behaviors needed to “get the job done.”

This is the science that results in students’ social, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral self-management and self-efficacy.

And these are the outcomes that every Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) school-based initiative and/or program in this country should target for all students.

_ _ _ _ _

But these initiatives or programs also need to recognize that not all students learn the same way, and that social, emotional, and behavior instruction needs to be adapted for students (a) from different cultural, racial, language, socio-economic, or family constellation backgrounds; (b) with different gender or psychosexual orientations; or (c) with one or more of the thirteen different disabilities recognized in federal law (i.e., IDEA).

And these initiatives or programs especially need to consciously identify and integrate the multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, and interventions required by students who are at-risk, underachieving, underperforming, unresponsive, and unsuccessful. . . in addition to the students who are demonstrating frequent or intense social, emotional, or behavioral challenges.

_ _ _ _ _

Where Does CASEL’s Framework Fit?

Critically, the multi-tiered research-to-practice instruction-to-intervention paradigm described above is not advocated, or even discussed, by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)—the most-dominant SEL voice in the country.

In fact, in addition to its global, difficult-to-assess outcome constructs (see below), CASEL’s framework has numerous shortcomings as CASEL is explicitly or implicitly on-record for:

Saying that districts and schools should have broad discretion in deciding what their SEL initiative will target and look like.

[This runs the risk that schools will implement unproven or the easiest-to-employ practices that are wasteful, ineffective, or counterproductive.]

_ _ _ _ _

Missing the importance of adapting SEL initiatives for students from different cultural, racial, language, socio-economic, or family constellation backgrounds; with different gender or psychosexual orientations; or with one or more disabilities.

[This may result in maintaining or increasing the SEL skill gaps between these students and others who may already have these essential skills.]

_ _ _ _ _

Missing the need for multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, and interventions for at-risk, underachieving, underperforming, unresponsive, and unsuccessful students, as well as those with significant social, emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health challenges.

[This potentially denies these students the opportunities to access the SEL instruction and, thus, to successfully learn and master the embedded skills.]

_ _ _ _ _

Largely publishing school and district SEL descriptive “testimonials” (to demonstrate that SEL and its framework is effective).

[These descriptive case studies report “outcomes” that are not based on random selection and control group comparisons, . . . their “evaluations” do not use objective data collection and sound statistical analysis techniques. . . and the “conclusions” that connect any favorable outcomes directly to the SEL program are inappropriate because the method and statistics do not demonstrate a “cause and effect” relationship.

_ _ _ _ _

Conclusion. Thus, as discussed in Part I of this Blog (see below), while CASEL may be largely responsible for the political and public relations-driven advancements of SEL, its research is weak and its pronouncements about SEL’s real contribution to the classroom may be overstated.

As noted above, CASEL’s “implementation” frameworks similarly has gaps and weaknesses. This framework has largely ignored, missed, or avoided a multi-tiered psychological foundation regarding students’ social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health, and it has failed to consistently utilize sound, objective, and defensible research and science-to-practice processes.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Reviewing Part I of this Blog Series on SEL

In Part I of this Blog, we discussed the following:

- The current media train of Social-Emotional Learning, how virtually all district leaders nationwide are “investing in SEL products,” and how most of the “press” is “positive press” because “Why would a school or district send out a press release that its SEL program has failed?”

[Parenthetically, U.S. News and World Report once again promoted SEL and CASEL (in a “human interest” story that was devoid of any hard, objective, research-based data) this past month.]

- The number of districts and schools that are implementing or purchasing “SEL programs and curricula” without independently and objectively evaluating (a) their research to determine if they are “ready” for field-based implementation; (b) whether they “fit” the demographics, students, and needs of their schools; and (c) whether they have a high probability of positively impacting the social, emotional, and behavioral student outcomes that they seek.

- How SEL’s recent popularity (and legitimacy—at least, in the media) is the result of a multi-year effort by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) to court and leverage foundations, politicians, well-regarded educators, and other powerful national figures to “independently” support its “movement.”

[CASEL’s website acknowledges that one of its goals is to establish a “national movement” supporting it version of SEL.]

- How many of the SEL “successes” touted in the media (and in some journals) are scientifically unsound, and how they confuse correlational (or contributory) outcomes for causal outcomes—assuming the latter by concluding that their SEL activities caused the student and other outcomes they report.

- How the three foundational SEL research studies, published by CASEL principals, have significant methodological and empirical flaws, and the difficulties in translating meta-analytic studies to effective field-based practice.

- How so many things have been reframed to take advantage of the SEL movement, and how SEL has become incredibly profitable for some publishers and vendors—leading to “marketing campaigns” that mask the questionable quality of some programs and curricula.

_ _ _ _ _

Agenda for this Blog Part II. In today’s discussion, we will analyze (a) CASEL’s foundational beliefs; (b) concerns with CASEL’s SEL student-focused outcomes; and (c) a more defensible science-to-practice approach to implementing valid SEL strategies.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaws in CASEL’s SEL Foundational Beliefs

CASEL defines Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) as:

The process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.

To guide implementation, CASEL provides a “framework” with five core competencies at the center (see below), and concentric layers of classroom, school, and home/community implementation. But, as alluded to above, CASEL’s has not wanted to “package” its work into a “one size fits all” model or set of strategies.

Instead, CASEL states that:

Research has shown that social and emotional development can be fostered, and social and emotional skills, attitudes, and behaviors can be taught using a variety of approaches:

* Free-standing lessons designed to enhance students’ social and emotional competence explicitly.

* Teaching practices such as cooperative learning and project-based learning, which promote SEL.

* Integration of SEL and academic curriculum such as language arts, math, social studies, or health.

* Organizational strategies that promote SEL as a schoolwide initiative that creates a climate and culture conducive to learning.

_ _ _ _ _

As such, CASEL says that every district and school should create its own version of SEL using “a strategic, systemic approach that involves everyone, from district and school leaders to community partners to family members, working together to ensure students receive the support they need.”

This “strategic, systemic approach” is guided by CASEL’s “School Theory of Action framework”—that actually is no different than any sound strategic planning approach applied to school and schooling:

- Develop a vision that prioritizes academic, social, and emotional learning.

- Conduct an SEL-related resources and needs assessment to inform goals for schoolwide SEL.

- Design and implement effective professional learning programs to build internal capacity for academic, social, and emotional learning.

- Adopt and implement evidence-based programs for academic, social, and emotional learning across all grades.

- Integrate SEL at all three levels of school functioning (curriculum and instruction, schoolwide practices and policies, family and community partnerships).

- Establish processes to continuously improve academic, social, and emotional learning through inquiry and data collection.

_ _ _ _ _

Critique

All of this sounds well and good. On the one hand, there is little on the surface to disagree with.

On the other hand, virtually all districts do strategic planning. And a list of “possible SEL activities” does not guide schools in the decision-making processes needed to determinewhich SEL activities will result in the most effective and efficient student outcomes.

Thus, the descriptions above (taken directly from the CASEL website) reinforce my assertion that,

“SEL is whatever a district or school decides it is.”

Beyond this, while CASEL’s outlined strategic planning process has the necessary steps, there are far too many examples where districts and schools have not effectively used these steps to address their students’ academic needs—never mind their social, emotional, or behavioral needs.

So why would we expect districts and schools to be more strategically successful when it comes to social and emotional learning?

The ultimate point here. . . is that ten districts or schools could use the CASEL guidance above—and the support materials from its website—and end up with ten different ways “to do” SEL . . . with virtually no assurance that any of them will successfully attain any positive, sustained changes in students’ social, emotional, and/or behavioral proficiency.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaws in CASEL’s Targeted Outcomes. . . And How They are Evaluated

CASEL has been very concerned, over the past number of years, about the quality of SEL assessment and evaluation tools in the field. These assessment tools typically measure the efficacy of specific SEL curricula or programs relative to student outcomes, while the evaluation tools typically measure the efficacy of multifaceted, systemic SEL initiatives.

CASEL concerns were described in a just-released CASEL document on SEL Competency Assessments:

The field of SEL competency assessment is growing rapidly, and a lot of promising research and development is underway. However, there is less consistency across frameworks and less clarity about terminology and developmental progressions than in more established fields.

Also, few SEL assessments have gone through the validation process typical of most large-scale academic assessments. . . It is also important to consider that most SEL assessments were not specifically developed for the purpose of comparing schools, and little research exists to determine whether currently available assessments have the precision necessary to make such comparisons.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, while this statement documents CASEL’s concerns that few assessment and evaluation tools have been validated to measure the effectiveness of SEL programs or initiatives, CASEL has nonetheless “accepted” the integrity of the assessment tools in over 200 research studies that it used in the three meta-analytic studies that are most-often referenced to validate SEL.

The significant flaws in these meta-analytic studies—Payton (2008), Durlak (2011), and Taylor (2017)—were critically reviewed in Part I of this Blog Series.

[CLICK HERE for Part I]

All of this leads to a critical question: If weak evaluation measures and approaches result in questionable research results, how can CASEL use these research results to support its meta-analytic statements that “SEL works”?

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to CASEL’s targeted SEL student outcomes, these are similarly flawed.

The most critical flaw is that CASEL’s outcomes are largely constructs, and not specific behaviors . . . and constructs cannot be reliably or validly measured because they are not discretely observable.

Below are the constructs that CASEL specifically defines as its primary SEL outcomes:

SELF AWARENESS

- Labeling one’s feelings

- Relating feelings and thoughts to behavior

- Accurate self-assessment of strengths/challenges

- Self-efficacy

- Optimism

SELF MANAGEMENT

- Regulating one’s emotions

- Managing stress

- Self-control

- Self-motivation

- Setting and achieving goals

SOCIAL AWARENESS

- Perspective-taking

- Empathy

- Appreciating diversity

- Understanding social and ethical norms for behavior

- Recognizing family, school and community supports

RELATIONSHIP SKILLS

- Building relationships with diverse individuals/groups

- Communicating clearly

- Working cooperatively

- Resolving conflicts

- Seeking help

RESPONSIBLE DECISION MAKING

- Considering the well-being of self and others

- Recognizing one’s responsibility to behave ethically

- Basing decisions on safety, social and ethical considerations

- Evaluating realistic consequences of various actions

- Making constructive, safe choices about self, relationships and school

Once again, as is evident from this list, few (if any) of these SEL “outcomes” are directly observable, measurable, or behaviorally-specific. In addition, at face value, none of these constructs can be specifically taught until they are behaviorally operationalized.

Said a different way: If you want to teach social-emotional learning skills, you need to teach specific interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills.

If you want to demonstrate that an SEL program or initiative is successful, you have to measure the social, emotional, and behavioral competence and self-management skills of the students involved.

_ _ _ _ _

The Need to Teach Skills

The Stop & Think Social Skills Program was identified in the early 2000s as an evidence-based program by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and listed on its Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (SAMHSA; NREPP).

Historically, the program (as a major component of its school improvement “umbrella” Project ACHIEVE) was also listed as a “Promising Practice” by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and it was identified as a CASEL “Key Select Program.”

Using the Stop & Think Program as an exemplar, the differences between an SEL program anchored by constructs versus anchored by skills is apparent.

For example, twenty of the prototypical skills taught in the Stop & Think Social Skills Program are:

SAMPLE CORE SKILLS

- Listening

- Following Directions

- Asking for Help

- Ignoring Distractions

- Dealing to Teasing

- Contributing to Discussions/Answering Classroom Questions

- Waiting for an Adult’s Attention- How to Interrupt

- Dealing with Losing

- Apologizing

- Dealing with Consequences

SAMPLE ADVANCED SKILLS

- Deciding What to Do

- Asking for Permission

- Joining an Activity

- Giving/Accepting a Compliment

- Dealing with Accusations

- Understanding Your/Others’ Feelings

- Avoiding Trouble

- Dealing with Anger

- Dealing with Being Rejected or Left Out

- Dealing with Peer Pressure

_ _ _ _ _

SAMPLE CLASSROOM and BUILDING ROUTINE SKILLS

- Entering class

- Bringing the right materials to class

- Hanging coats and backpacks

- Lining up to leave school/The Dismissal skill

- Walking in line

- Bathroom behavior

- Walking safely in the hall

- Getting on the bus

- Riding on the bus

- Contributing to discussions

- Answering questions during lessons

- Completing seatwork or independent assignments

- Knowing when to tell an adult about a school safety issue

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to social, emotional, and behavioral competence and student self-management, these skills are taught using the following science-to-practice elements:

- Using cognitive-behavioral scripts so that students learn and master the specific internal (cognitive) steps and the external observable (behavioral) actions needed to execute each skill;

For example, the adolescent script for Dealing with Teasing is:

1. Take deep breaths and count to five.

2. Think about your good choices. You can:

a. Ignore the teasing.

b. Ask the person to stop in a nice way.

c. Walk away or back away.

d. Find an adult for help.

3. Choose and Act Out your best choice.

_ _ _ _ _

- By having students positively practice the different skills in instructional role-plays to ensure that they can eventually perform the scripts and behaviors independently at a level of automaticity;

_ _ _ _ _

- By teaching students how to control their negative thoughts and emotions, and then applying these self-management strategies to specific skills during the role-plays (so that they can eventually demonstrate their skills “under conditions of emotionality); and

_ _ _ _ _

- Using a Teach, Apply, Infuse pedagogical/teaching process (where specific social skills are typically taught within a scaffolded, two-week instructional cycle) so that students have systematic learning experiences that result in true competence and self-management.

[CLICK HERE for a previous Blog describing the Stop & Think Social Skills teaching process more completely]

[CLICK HERE for a free Technical Assistance document (see below) on The Stop & Think Social Skills Program: Exploring its Research Base and Rationale]

_ _ _ _ _

Tying the Knot

When students are able to control their emotions, think clearly through the social demands of different interpersonal situations, internally plan their responses using sequential steps, and then behaviorally execute and evaluate their actions. . . they are demonstrating social, emotional, and behavioral competence and self-management.

But. . . like a basketball or soccer team, an orchestra or chorus, a theatre or drama troupe. . . these skills need to be taught, practiced, mastered, and demonstrated—under conditions of emotionality—at a level of automaticity.

Embedded in these processes, certainly, are CASEL’s five foundational “pillars” (i.e., self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making).

But CASEL provides no explicit science-to-practice guidance on how to translate its constructs into the cognitive-behavioral skills and scripts needed for student success. Moreover, there is so much variability among the programs in CASEL’s Program Guide that there is no assurance that any program will have a high probability of success.

Beyond this, as discussed in the next section below, CASEL has not identified a valid scientific model (its “framework” does not qualify here) wherein an SEL program will be successful.

Finally, and once again, CASEL does not address the fact that different at-risk, underachieving, underperforming, unresponsive, and unsuccessful students need strategic or intensive multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, and interventions in order to attain social, emotional, and behavioral competence.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

An Evidence-based, Field-tested, Science-to-Practice SEL (Alternative) Model

Project ACHIEVE is a comprehensive preschool through high school continuous improvement and school effectiveness program that has been implemented in urban, suburban, and rural districts across the country since 1990. One of Project ACHIEVE’s seven interdependent components is its Social and Emotional Learning/Positive Behavioral Support System (SEL/PBSS) component which includes The Stop & Think Social Skills Program. Another is its academic and behavioral multi-tiered service and support (MTSS) component. Project ACHIEVE, and its SEL/PBSS and MTSS components, has been recognized as an evidence-based program as described earlier in this Blog.

Relative to the current discussion, an effective multi-tiered SEL program should be based on a valid, field-tested science-to-practice model that has been implemented in multiple settings, with a diverse range of students and staff, and under a variety of challenges and conditions.

This perfectly describes Project ACHIEVE with its 35-year history of implementation in every state in the country, including thirteen years as the PBIS, MTSS, and school improvement model for the Arkansas Department of Education’s State Improvement/Personnel Development Grant.

Critically, a model involves an explicit set of strategically scaffolded and sequenced actions, approaches, activities, and strategies that are needed for student, staff, and school success. While the sequence may be adapted to meet the strengths and resources, weaknesses and limitations, barriers and threats, and unique needs of a school or district, the model identifies what elements are prerequisite, essential, and non-negotiable—relative to the desired outcomes, and what elements can be substituted, modified, or adapted.

In contrast, a framework is a list of actions, approaches, activities, and strategies that a school or district may choose to implement, but they typically are not scaffolded or sequenced.

When schools or districts implement a framework, they are largely “choosing from the available menu.” Thus, if they only want to have “dessert” (for example, choosing the easiest or most popular items in the framework), that is up to them. In the final analysis, though, their choices may not lead to the outcomes that they need—even though they are “pleased” with what they have implemented.

Another limitation of a framework involves the challenge of evaluating and determining the efficacy of the framework.

Indeed, if five schools in the same district use the same framework, but choose different activities or strategies to implement from the framework’s menu, the effectiveness of framework cannot be appropriately evaluated. This is because the evaluation needs to focus on how the specific activities or strategies contributed to each school’s outcomes. Here, you have five different assortments of activities or strategies. . . you are measuring “apples, oranges, bananas, pineapples, and kiwi fruit.”

This does not occur with Project ACHIEVE because, as noted above, Project ACHIEVE coordinates the activities and strategies within it seven interdependent components in planned, proven, strategic, and sequenced ways.

_ _ _ _ _

Project ACHIEVE’s SEL/PBSS Model

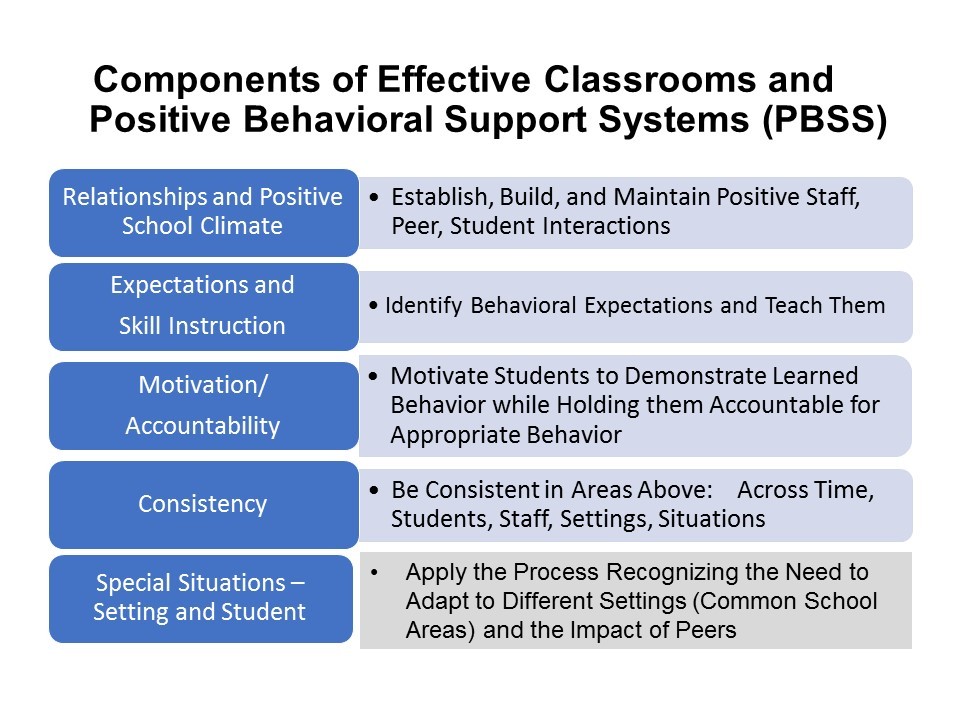

There are five critical elements in Project ACHIEVE’s SEL/PBSS system that interdependently facilitate school discipline, classroom management, and students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management (see the figure below):

- Positive School and Classroom Climate, and Staff and Peer Relationships

- Explicit Prosocial Behavioral Expectations in the classrooms and common school areas and Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skill Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Consistency relative to the implementation of all of the above components

- The Application of the above to all school settings, peer interactions (including those that prevent teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression), and individual students’ specific conditions and needs

CLICK HERE for more information the Free Study Guide that accompanies this PBSS model.

Activities and strategies within these elements are systematically implemented across the four-year multi-tiered blueprint that (a) begins with an on-site Plan-for-Planning meeting (that includes the completion of a needs assessment, resource analysis, and strategic action plan); (b) continues by building on the effective practices and resources of the school or district; (c) involves reaching a consensus on the multi-tiered procedures—focusing not just on prevention, but also on the challenging students already identified and in need of immediate services—that all district schools will use; and (d) immediately builds in both short- and long-term evaluations of student, staff, and school outcomes to ensure that successes are sustained, and mid-course corrections are quickly implemented.

Some of the activities across these five elements include:

- Schools align their organizational and committee structure with the characteristics of effective schools, and looks at their Mission Statements and committee contributions to those missions.

- Committees and School Improvement Teams write and approve their School Improvement Plans, integrating start-up activities for Year 1.

- Building committees meet on a monthly basis, with quarterly evaluations to determine progress toward School Improvement Plan goals and outcomes.

- Schools complete and "roll-out" their Behavioral Matrices, the student accountability document that sets the behavioral standards for the building.

- Staff are taught and begin to implement the Stop & Think Social Skills Program (or an equivalent SEL program). Mental health specialists bring the Stop & Think Parenting Program (or the equivalent) out to parents and the community.

- The Multi-Tiered Student Assistance Team (SAT; Pre-referral/Early Intervention Team) is trained on the SAT's Data-based Problem-Solving process, and begin case study practice to build proficiency.

- The School Discipline Committee learns and begins to use Special Situation Analyses, as relevant, to improve behavior in common areas of the schools and as related to Teasing, Taunting, Bullying, Harassment, Hazing, and Fighting.

- Staff learn and implement the Educative Time-Out process.

- Staff learn and begin to use the SAT Data-based Problem-Solving process, and Grade-level SAT teams and meetings are established.

- A formal Articulation Process occurs at the end of the school year to transfer the student, staff, and school "lessons learned" to the new school year.

Critically, Project ACHIEVE’s multi-tiered SEL/MTSS system integrates (a) the psychology of child and adolescent learning, development, social, and normal and abnormal behavior with (b) the psychology of group and organizational behavior as embedded in implementation science.

From a student perspective—especially given its primary social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health self-management goals, Project ACHIEVE’s model and psychological foundation means that it addresses the following areas using integrated, science-to-practice approaches:

- School safety and prevention,

- Positive school culture and classroom climate,

- Classroom discipline and management,

- Student engagement and self-management,

- Social Skills training and teaching 21st Century SEL/Soft Skills

- Productive student interactions in cooperative and project-based groups,

- Student trauma and trauma-sensitive practices,

- Teasing and bullying,

- Harassment and physical aggression,

- Chronic student absences and school/class tardiness,

- Office discipline referrals and suspensions/expulsions,

- Disproportionality and retiring zero tolerance policies, and

- Preventing and responding to students’ mental health status and needs.

Functionally, this alleviates the need for separate (sometimes, competing) initiatives, programs, or strategies. This makes planning, training, and implementation more effective and efficient, and it increases the probability of student, staff, and school success. Indeed, when districts and schools try to address the different areas above using different programs—all of which are ultimately implemented by classroom teachers, they realize that they do not have the time, resources, and expertise to succeed. In addition, the programs are often met with staff resistance that translates into a lack of implementation fidelity, and other unintended negative results.

_ _ _ _ _

For more information on Project ACHIEVE’s SEL/PBSS/MTSS model, strategies, and successes, please see a recent, earlier Blog:

Elementary School Principal’s Biggest Concern: Addressing Students’ Behavior and Emotional Problems. The Solution? Project ACHIEVE’s Multi-Tiered, Evidence-Based Roadmap to Success (July 7, 2018)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

The primary goal of this two-part Blog Series was to help districts and schools that are “looking for SEL in all the wrong places,” because they are placing too much trust in CASEL (and others’) public relations-driven SEL movement.

Indeed, too many districts and schools have already chosen incomplete, ineffective, and inconsequential (if not counterproductive) SEL strategies and approaches that are wasting classroom time, squandering schools’ precious resources, and undermining districts’ professional development decisions.

It’s time to take a Time-Out.

District and school leaders need to “take a breather” to look at what they are doing, planning, or considering within their SEL initiatives.

There is no pressure to implement anything right now.

In fact, at this point in the school year, most districts and schools should be strategically building their “SEL infrastructure” for implementation during the next school year.

And there still are many months available to build the right infrastructure . . . that will lead to quality implementation, and sustainable student, staff, and school results.

For when the wrong SEL programs or approaches are implemented, unintended results occur. Indeed, an SEL “failure” not only negatively impacts student success now, but it potentially undermines student and staff confidence—creating resistance to the next SEL initiative in the future.

Thus, today’s SEL failures may have a generational impact on tomorrow’s potential successes. Today’s SEL failures may lower or close tomorrow’s “window of change” for a district or school.

There are sound, field-tested, evidence-based SEL models. Typically, they incorporate many of the constructs and global approaches advocated by CASEL, but they prevent or eliminate many of the CASEL flaws discussed in this two-part Blog.

Districts and schools need to strategically build their “SEL infrastructures” with these models. SEL is a noble and needed addition to our school and schooling process. It can directly address students’ social, emotional, behavioral, and mental health needs—from prevention to strategic intervention to intensive need/student crisis management.

As noted in the Introduction, all students need to learn, master, and apply effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control and coping skills.

Let’s do it once. Let’s do it right. And let’s do it so that we can connect our student outcomes directly to our staff and school actions.

_ _ _ _ _

The Coming Federal School Climate Transformation Grant

At some point during the coming months, the U.S. Department of Education will announce the availability of the second School Climate Transformation Grant. The first Grant (June, 2014) resulted in awards to over 70 school districts nationwide for five years. Depending on the size of the district/school, the total Grant Awards ranged from $1 million to $4.5 million.

The coming Grant will focus on virtually all of the areas discussed in this two-part Blog series.

If you are interested in exploring the possibility of applying for this Grant, and including Project ACHIEVE’s SEL/PBSS/MTSS model as the foundation of your implementation, please contact me immediately.

For the first Grant, I helped 15 school districts write their grant proposals and two of these proposals were successful (in Michigan and Kentucky). I can write virtually the entire grant proposal for you, and guide you through the submission process.

Best,