Underachieving, Unresponsive, Unsuccessful, Disabled, and Failing Readers

Diagnostic Assessment Must Link to Intervention: If We Don’t Know “Why,” We Can’t Know “What” (Part II)

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Last month, I was asked to lead an Invited Workshop on “Academic Interventions for Struggling Students” at the annual convention of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) in Baltimore. Most of my focus was on the millions of children and adolescents nationwide who are struggling—if not failing—in reading and literacy.

While this was my third consecutive year to give this NASP convention presentation, I prepared the same way I always prepare: Making believe that I had never given this presentation before. That is, I re-reviewed the research, re-googled to find new perspectives, and re-thought my past approaches to the topic.

But. . . for all the “new” research and perspectives in reading instruction and intervention, not much has changed. To summarize the “state of the field”—and to revisit some of the themes from Part I of this Blog Series—the following points are evident:

- Too many students—especially those living in poverty—enter school with fewer early literacy experiences (at home and/or because they did not attend preschool) and fewer prerequisite literacy skills (e.g., phonemic awareness and receptive/expressive language). . . and some never catch up.

_ _ _ _ _

- Too many students are not getting sound, evidence-based, and differentiated core instruction in reading. . . and this necessitates reading interventions that would not be necessary if these students had originally received effective instruction.

I call these students “Instructional Casualties,” and yes, the statement above is circular.

Critically, most of these students can learn to read, they just are not getting the opportunities (through effective instruction) to learn to read.

_ _ _ _ _

- Too many teachers, especially at the Elementary school level, are developing literacy lessons alone, in PLCs, or from the internet, and too many schools are purchasing reading series that do not use the established cognitive science underlying effective literacy instruction.

When these reading lessons are taught in the absence of a well-sequenced literacy scope and sequence, and/or when they are delivered inconsistently by teachers at the same grade level, students do not learn or become proficient readers immediately or over time.

While most published reading series typically provide the scope and sequence roadmaps that result in more consistent instruction, these curricula often focus more on the organization and delivery of their lessons, and less on the criteria of learning and mastery, how to sensitively evaluate for learning and mastery, and what to do when learning and mastery does not occur. Thus, delivery is valued more than student learning outcomes.

Critically, when instruction does not focus on producing student skill and content mastery, teachers often are satisfied with delivering the curriculum, rather than educating proficient readers.

When students fail here, they are considered “Curricular Casualties.” As above, most of these students can learn to read, they just are not getting the opportunities (due to ineffective curricula) to learn to read.

_ _ _ _ _

- When students demonstrate persistent or significant reading struggles, too many schools continue to use an archaic “response-to-intervention” framework, and they do not effectively utilize a data-based problem-solving process that links the functional assessment of students’ literacy skills and deficits to multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, and interventions.

[CLICK HERE for our free monograph, A Multi-Tiered Service & Support Implementation Blueprint for School & Districts: Revisiting the Science to Improve the Practice]

_ _ _ _ _

- Students continue to be identified (or not identified) as having learning disabilities in reading using, for example, discrepancy or patterns of strength and weakness formulas that have never been validated.

_ _ _ _

- Many students found “eligible” for special education services as students with “reading disabilities,” do not have disabilities.

These students are typically Instructional Casualties, Curricular Casualties, Early (or No) Intervention Integrity Casualties, or they are “qualified” as “students with disabilities” by Special Education Eligibility Teams because their schools have no other way to get them more intensive (and needed) interventions.

_ _ _ _ _

- For most students who have legitimate reading disabilities, they are still more—relative to pedagogy, instruction, learning, and mastery—like their typical peers than unlike them.

_ _ _ _ _

- The historical lack of an “aptitude by treatment” interaction persists.

That is, there are no valid or established diagnostic reading deficiency patterns—psycho-educationally, neuro-linguistically, or neuropsychologically—that automatically link to specific skill-focused interventions or curriculum-focused intervention programs/packages.

This means that most reading interventions need to be conceptualized as “controlled science experiments” that (a) are initially implemented in a “small-scale” way; (b) have clear short- and long-term criteria defining their success; (c) use formative and summative assessments that are sensitive to these criteria; and that (d) do not “scale-up” until the objective data validate their efficacy.

_ _ _ _ _

- Finally, when educators search for “evidence-based” literacy interventions, they are “rewarded” with a “scavenger hunt in purgatory.”

The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) and other U.S. Department of Education-funded National Technical Assistance Centers have identified precious few literacy interventions that successfully remediate student deficits in the five recognized areas of reading.

Moreover, the different Practice Guides produced by the WWC are OK, but they don’t reveal any dramatic intervention suggestions for anyone who is knowledgeable in this area.

_ _ _ _ _

A Brief Review of Part I

In Part I of this Blog Series, we discussed the “new and current” rush of policy, publication, media, and legal attention to the quality of literacy instruction—and student outcomes—in our nation’s schools.

While triggered by the most-recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results, the impact of this persistent problem area has been recently reinforced by:

- A February 20, 2020 legal settlement whereby the state of California agreed to provide $53 million for early literacy instruction to resolve a 2017 lawsuit asserting that petitioning students’ constitutional rights were violated when schools failed to teach them to read.

- An influx of state legislatures that are passing laws requiring pre-service and classroom teachers to be taught—and to demonstrate their proficiency in—the science of reading.

- Two recent national surveys that revealed how many school principals—especially in schools serving more students of color—felt that they were not fully supporting students with disabilities, and that they felt unprepared to meet these students’ needs.

The Part I Blog next cited a recent (December 4, 2019) series of articles in Education Week, “Getting Reading Right,” that documented these and other problems in literacy training and instruction.

Implicitly, these articles emphasized that the current national discussion and all of the policy, practice, legislative, and training/professional development efforts to date are missing three critical factors:

- We are not conceptualizing literacy instruction and students’ reading proficiency within a systemic, ecological, multi-factored, and multi-tiered continuum that is built on evidence-based blueprints.

- We are developing and implementing policies, procedures, processes, and practices in disorganized, segmented, and disparate ways such that “whole has holes, and the parts never add up to a whole.”

- We are not effectively using the psychoeducational research relative to child development, learning and cognition, psychometrics and assessment, and data-based decision-making and evaluation.

The rest of this Part I Blog presented six essential blueprints that must be interdependently considered when “piecing together” a sound multi-tiered system of literacy instruction and supports.

These blueprints included the following:

- Blueprint 1: The Principles Underlying Effective Educational Policy

- Blueprint 2: A Psychoeducational Science-to-Practice Blueprint for Effective Literacy Instruction and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

- Blueprint 3: Understanding the Instructional Environment and Its Contribution to Student Reading Proficiency

- Blueprint 4. The Data-based Problem-Solving Blueprint for Struggling and Failing Readers

- Blueprint 5. The Seven High-Hit Reasons Why Students Struggling or Fail in Reading

- Blueprint 6: The Multi-tiered Positive Academic Supports and Services Continuum

In Part II of this Blog Series, we will discuss the multi-tiered questions (from Blueprint 4) needed to address the needs of struggling readers and students with reading disabilities, and the state of literacy intervention (linking Blueprint 5 and Blueprint 6).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Literacy Problem Identification and Critical Analysis Questions

In Part I, we outlined the four data-based problem-solving components within our multi-tiered systems of support. We also noted that, while the data-based problem-solving process analyzes the three components of the Instructional Environment (the Teacher-Instructional, Curriculum, and Student components, respectfully), it also ecologically analyzes Classroom and Peer, School and District, and Home and Community factors.

The four data-based problem-solving blueprint steps are:

- Problem Identification

- Functional, Diagnostic, or Root Cause Problem Analysis

- Services, Supports, Strategies, Interventions, or Programs

- Progress Monitoring/Formative and Summative Outcomes-Based Evaluation

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to Problem Identification, one of the first steps is a comprehensive interview with a struggling student’s current and past teacher(s), parents/guardians, and others (e.g., literacy coaches or intervention specialists) who have worked with the student.

We have developed a Problem Identification Interview protocol to guide this process. It can be found in our comprehensive monograph:

A Multi-Tiered Service and Support Implementation Guidebook for Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap

[CLICK HERE to Review (and potentially purchase) this Best-Selling publication. Use Code 15%OFF through April 10th for 15% Off!!!]

_ _ _ _ _

Another essential Problem Identification activity, when students are demonstrating significant or prolonged reading struggles, is to determine what content and skills they have learned, mastered, and are able to independently apply in the five areas of literacy (phonemic awareness, phonetic decoding, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension). This is accomplished by integrating the data from classroom performance and assessments, diagnostic assessments, interim and progress monitoring assessments, and high stakes proficiency assessments.

When students’ current mastery levels are graphed or “plotted”—with these data—across a sound grade-level-anchored literacy scope and sequence, the differences between their current functioning and their grade-level placements identify the “gap” between where they are and where they should be.

For example, if a student is in the middle of fifth grade but is functioning at the beginning third grade level in decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, then that student is approximately two skill years behind grade-level expectations.

Functionally, when given beginning of third grade reading passages, this student will be reading and understanding the vocabulary and comprehension questions in that passage at a 90 percent or above criterion level (at least at the 50th percentile). When given beginning of fourth grade or fifth grade, respectively, passages to read, the same student will show progressively less skill proficiency. . . for example, at the 25th percentile for the fourth grade material, and at the 10th percentile for the fifth grade material.

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to Problem Analysis, the primary goal is to complete a root cause analysis of a student’s past and present Instructional Environments (i.e., the Teacher-Instructional, Curriculum, and Student components, respectfully), and ecological analyses of the Classroom and Peer, School and District, and Home and Community components in a student’s past and present “literacy life.”

In most cases, root cause analyses of the Instruction Environment result in causal explanations. . . that identify the goals of the intervention process.

For example, if a teacher is not effectively teaching the student literacy skills, or is not implementing a classroom modification with fidelity, the interventions should focus on changing the teacher’s instructional interactions which should, concomitantly, improve the student’s learning and mastery.

In most cases, ecological analyses of the other components result in correlational, contributory, or contextual explanations. . . that identify supportive goals for the intervention process.

For example, if a student struggles to learn in a school averaging 25 students for each teacher, or comes from a low socio-economic status home that can’t many books. . . the intervention is not to change the student-to-teacher ratio (especially when most other students are progressing, and district budgets are uncompromising), or to provide books for the home (especially when other students experiencing similar economic conditions are learning to read).

The first scenario’s intervention might include (a) providing the student preferential seating to minimize the impact of the large (but not unprecedented) number of students in the classroom; (b) ensuring that the teacher is periodically using small group, differentiated instruction; and/or (c) teaching the student attention-control strategies such that s/he focuses more on the instruction, and less on the number of students in the room.

The second scenario’s intervention might include (a) teachers’ previewing each unit (in English—as well as in other courses that depend on independent reading) with the student to ensure that s/he has the prerequisite literacy skills, content, or experiential knowledge—and closing any gaps through remediation as needed; (b) providing tutoring for the student to close larger or more prominent gaps; and/or (c) giving the student additional “free reading” time at school, while encouraging him/her to use the school library or computer-based support programs.

The point here is: Most Classroom and Peer, School and District, and Home and Community correlational effects are addressed through interventions addressing one or more Teacher-Instructional, Curriculum, and/or Student factors.

_ _ _ _ _

To briefly expand: The Instructional Environment root cause analysis focuses on evaluating a student’s longitudinal history of literacy learning and mastery from preschool to the present. The goal is to determine why the student is (has) experiencing(ed) underachievement, poor achievement, slow achievement, or no achievement in (as relevant) the five areas of literacy.

When completing this root cause analysis, there are a series of standard questions that frame the assessment for the Instructional Environment components, examples of these diagnostic/problem analysis questions include the following:

Questions Regarding Past and Present Teacher Characteristics/Conditions (written in present tense):

1. Does the instructional environment support the learning/educational process?

2. Is the teacher being instructionally effective with the referred student, and is the instruction programmed for student success?

3. Is the teacher adapting the curriculum such that there is an appropriate student-curriculum match?

_ _ _ _ _

Questions Regarding Past and Present Curricular Characteristics/Conditions (written in present tense):

1. Does the curriculum, related to the “problem at-hand” specify the particular objectives and skills that the student is expected to master for each skill, performance benchmark, and/or instructional unit?

2. Does the curriculum task analyze specific skills, when appropriate, such that sequential and mastery-oriented learning results for all students?

3. Does the curriculum provide a range of levels to accommodate the different cognitive and language levels that might exist within an integrated classroom?

_ _ _ _ _

Questions Regarding Past and Present Student Characteristics/Conditions (written in present tense):

1. Does the student have the prerequisite skills for the required/desired tasks?

2. Does the student have the prior learning strategies to facilitate the advanced learning desired?

3. Does the student have the self-competency, cognitive/metacognitive, motivational, social/interactive, and other learning-supporting skills needed to be successfully involved in the desired task?

_ _ _ _ _

Once again, all of the Instructional Environment Root Cause Analysis questions can be found in our comprehensive monograph:

A Multi-Tiered Service and Support Implementation Guidebook for Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap

[CLICK HERE to Review (and potentially purchase) this Best-Selling publication. Use Code 15%OFF through April 10th for 15% Off!!!]

_ _ _ _ _

Linking the Seven High-Hit Reasons Why Students Struggle in Reading with Intervention Actions

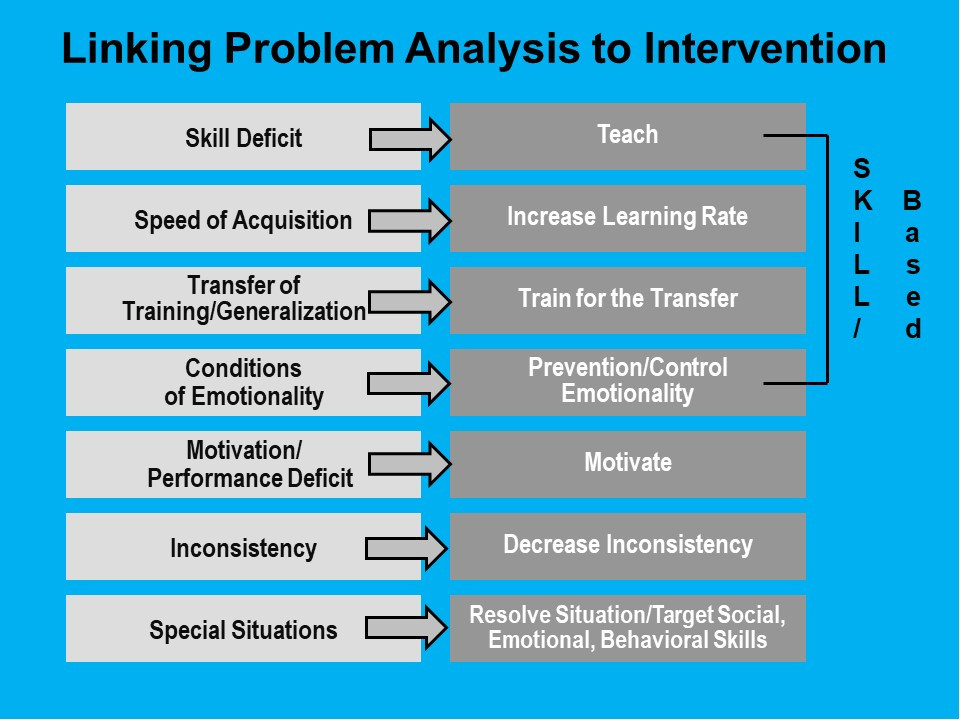

In Part I of this Blog Series, we identified the seven high-hit student-centered reasons why students struggle in reading.

These were:

- High Hit #1: Skill Deficits. The student has skill deficits in critical areas of reading. She or he has either not been exposed to effective reading curricula or instruction, or she or he is not learning successfully.

- High Hit #2: Speed of Acquisition. The student is learning, but his/her speed of learning and mastery is slower than other students—either relative to instruction in-the-moment, or instruction over the long-term.

- High Hit #3: Generalization. The student is learning discreet, specific, or isolated skills, but she or he is not blending, integrating, transferring, applying, or generalizing these skills such that—ultimately—she or he is able to decode, read fluently, understand vocabulary, and/or derive meaning and comprehension from text.

- High Hit #4: Conditions of Attribution or Emotionality. The student does not believe that she or he can successfully learn to read, or she or he is experiencing a high enough level of emotionality around some or many parts of the reading (or assessment) process, and this is undermining his or her progress and proficiency.

- High Hit #5: Motivation. The student is not motivated to learn to read. The student has the capacity to learn, or has learned literacy skills in the past, but (now) is not choosing to learn.

- High Hit #6: Inconsistency. The student has or is experiencing (typically) instructional, curricular, or motivational inconsistency that has or is undermining the literacy learning and mastery process.

- High Hit #7: Special Situations. Some special, significant, intense, unique, or individualized situation or circumstance is present that is interfering with the students’ learning.

These situations may require (a) different instructional approaches to reading and/or intensive interventions (e.g., dyslexia); (b) the use of technology-based assistive supports (e.g., students with traumatic brain injured or cerebral palsy); or (c) the recognition that certain reading skills may never be learned but that, through compensatory strategies, literacy (i.e., the comprehension of text) can.

_ _ _ _ _

While some students have a combination of these high-hit reasons, the primary intervention approaches that link to these high-hit reasons are depicted in the Figure below.

These links are:

- High Hit #1: Skill Deficits. Interventions here must involve teaching the specific literacy skills that the student has not been taught, has not been taught effectively, or has not learned and mastered. Among the primary intervention questions are: (a) how and where the student will learn these unlearned skills; (b) who will provide the instruction; and (c) what instructional intensity will be needed (e.g., how many days per week, and minutes per day).

- High Hit #2: Speed of Acquisition. Assessments in this area must determine if the student is learning as fast as s/he is able—given his/her cognitive ability and/or learning capacity.

For example, some students can only make, for example, eight months of academic progress for every ten months in school. They cannot learn any faster. Indeed, any attempts to “help” them learn more quickly will not only fail, but may introduce a level of frustration that will actually impair their learning and learning speed.

The “intervention” for these students is to continue to teach them at their instructional/mastery level, and let them continue to progress at their own rate.

Other students in this high-hit area will respond to interventions that will help increase their learning speed. Depending on the root cause assessment results, these interventions most often involve skill remediation, learning approach accommodations, or curricular modifications (see below).

- High Hit #3: Generalization. Interventions here assist students, who are learning discreet, specific, or isolated skills, to blend, integrate, transfer, apply, or generalize these skills such that—ultimately—they able to decode, read fluently, understand vocabulary, and/or derive meaning and comprehension from text.

- High Hit #4: Conditions of Attribution or Emotionality. Interventions here focus on decreasing or eliminating students’ negative beliefs, expectations, or attributions, and/or the stress or emotionality associated with all or part of the reading process. This helps students believe they can successfully (learn to) read, and/or “frees” them up so they can learn and read without any emotional interference.

- High Hit #5: Motivation. Interventions here directly address the reason(s) why a student is not motivated to learn to read, or to use or apply literacy skills that have already been learned and mastered. There are a number of long-standing and very effective motivational interventions for students. The question is which one has the highest probability of success given the student’s history, attributions, and preference for certain incentives and/or consequences.

- High Hit #6: Inconsistency. Interventions here must be connected with the root cause and data-based functional assessment as this is typically a very complex area of concern. Briefly, though, interventions here work to (a) decrease or eliminate the instructional, curricular, or other inconsistencies identified, (b) re-establish a positive learning trajectory, while overcoming the skill and/or motivational impact and “history” of the past inconsistency, and (c) fade the interventions over time so that students progress over time without the need for external services or supports.

- High Hit #7: Special Situations. Interventions here are typically the most multi-faceted and/or complex. Depending on the results of the analyses, interventions here may require (a) different instructional approaches to reading and/or intensive interventions (e.g., dyslexia); (b) the use of technology-based assistive supports (e.g., students with traumatic brain injured or cerebral palsy); or (c) the recognition that certain reading skills may never be learned but that, through compensatory strategies, literacy (i.e., the comprehension of text) can.

For some students, as alluded to above, there are no interventions to “fix” their literacy skill gaps or disabilities. They can be literate, however. That is, they can learn to use compensatory strategies and/or technology-based assistive supports such that they can comprehend and derive full meaning from text.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

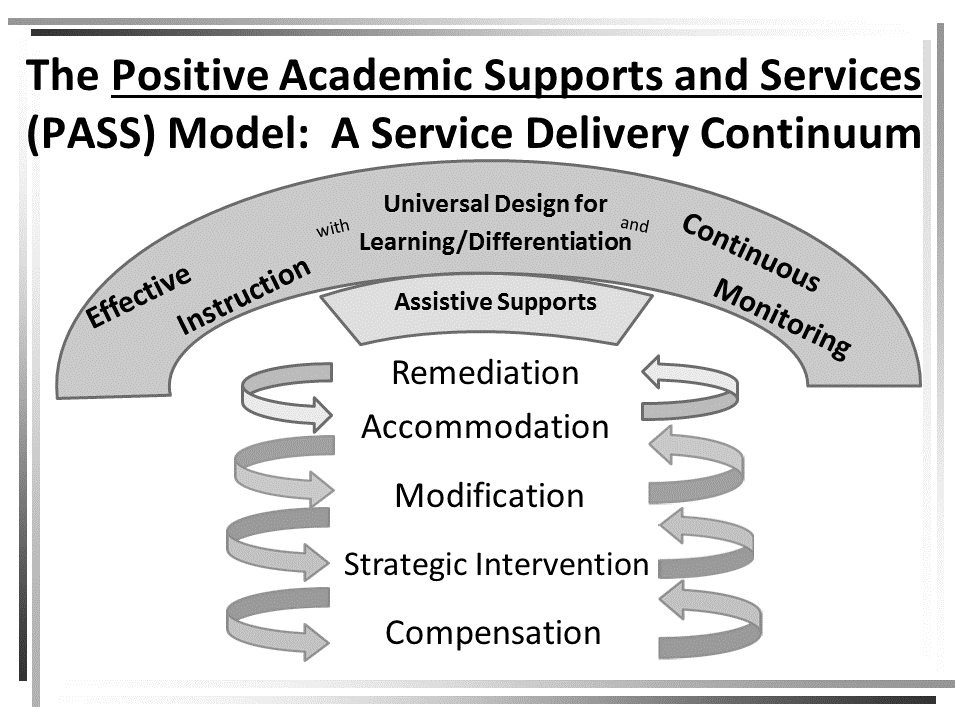

Blueprint 6: The Positive Academic Supports and Services (PASS) Continuum

As initially discussed in Part I of this Blog Series, grounded by effective, differentiated classroom instruction with well-designed progress monitoring and evaluation, the PASS continuum identifies services, supports, strategies, interventions, and programs—at different, student-needed levels of intensity—to address the root causes when students are struggling or failing to master different facets of literacy.

The PASS continuum consists of the following (see also the Figure below):

- Assistive Supports

- Remediation

- Accommodation

- Curricular Modification

- Targeted Intervention

- Compensation

The instruction- and intervention-related components are briefly described below.

Assistive Supports involve specialized equipment, technologies, medical/physical devices, and other resources that help students, especially those with significant disabilities, to learn and function—for example, physically, behaviorally, academically, and in all areas of communication. Assistive supports can be used anywhere along the PASS continuum.

Remediation involves strategies that teach students specific, usually prerequisite, skills to help them master broader curricular, scope and sequence, or benchmark objectives.

Accommodations change conditions that support student learning—such as the classroom setting or set-up, how and where instruction is presented, the length of instruction, the length or timeframe for assignments, or how students are expected to respond to questions or complete assignments. Accommodations can range from the informal ones implemented by a classroom teacher, to the formal accommodations required by and specified on a 504 Plan (named for the federal statute that covers these services).

Modifications involve changes in curricular content—its scope, depth, breadth, or complexity.

_ _ _ _ _

Remediations, accommodations, and modifications typically are implemented in general education classrooms by general education teachers, although they may involve consultations with other colleagues or specialists to facilitate effective implementation. At times, these strategies may be implemented in “pull-out,” “pull-in,” or co-taught instructional skill groups so that larger groups of students with the same needs can be helped.

If target students do not respond to the strategically-chosen approaches within these three areas, or if their needs are more significant or complex, approaches from the next two PASS areas may be needed:

Strategic Interventions focus on changing students’ specific academic skills or strategies, their motivation, or their ability to comprehend, apply, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate academic content and material. Strategic Interventions typically involve multidisciplinary assessments, as well as formal Academic Intervention or Individualized Education plans (AIPs or IEPs).

Compensatory Approaches help students to compensate for disabilities that cannot be changed or overcome (e.g., being deaf, blind, or having physical or central nervous system/neurological disabilities). Often combined with assistive supports, compensatory approaches help students to accomplish learning outcomes, even though they cannot learn or demonstrate specific skills within those outcomes. For example, for students who will never learn to decode sounds and words due to neurological dysfunctions, the compensatory use of audio or web-based instruction and (electronic) books can still help them to access information from text and become knowledgeable and literate. Both assistive supports and compensatory approaches are “positive academic supports” that typically are provided through IEPs.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, there are numerous components and strategies embedded in each of the areas above. Only through a comprehensive professional development experience—that includes using real case studies to demonstrate how to link assessment to specific multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, and interventions—can school personnel truly learn and build their sustained skill and capacity to address the needs of struggling students.

For districts and schools interested in discussing this professional development, please contact me at any time: knoffprojectachieve@earthlink.net.

Beyond this, while there is a sequential nature to the components within the PASS continuum, it is a strategic and fluid—not a lock-step—blueprint. That is, the supports and services are utilized based on students’ needs and the intensity of these needs. For example, if reliable and valid assessments indicate that a student needs immediate accommodations to be successful in the classroom, then there is no need to implement remediations or modifications just to “prove” that they were not successful. In addition, there are times when students will receive different supports or services on the continuum simultaneously. For example, some students will need both modifications and assistive supports in order to be successful. Thus, the supports and services within the PASS are strategically applied to individual students.

Beyond this, while it is most advantageous to deliver needed supports and services within the general education classroom (i.e., the least restrictive environment), other instructional options could include co-teaching (e.g., by general and special education teachers in a general education classroom), pull-in services (e.g., by instructional support or special education teachers in a general education classroom), short-term pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support teachers focusing on specific academic skills and outcomes), or more intensive pull-out services (e.g., by instructional support or special education teachers). These staff and setting decisions are based on the intensity of students’ skill-specific needs, their response to previous instructional or intervention supports and services, and the level of instructional or intervention expertise needed.

Ultimately, the intervention goal here is to provide students with early, intensive, and successful supports and services that are identified through the data-based problem-solving process, and implemented with needed integrity and intensity.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Brief Note on Interventions

I have done extensive research on different interventions at different grade levels for the five areas of literacy. While descriptions of these interventions are beyond the scope of this Blog Series, there are a number of principles that are important to follow.

These principles include:

- Diagnostic assessments and root cause analyses are the most effective ways to determine why students are presenting with different problems in literacy. When poor teacher/instructional processes or poor curriculum design and student matching are the predominant root causes, students may be struggling, but it is often not because they cannot learn.

When student characteristics or factors are predominant, then more student-focused interventions likely are needed.

_ _ _ _ _

- The historical lack of an “aptitude by treatment” interaction persists.

That is, there are no valid or established diagnostic reading deficiency patterns—psycho-educationally, neuro-linguistically, or neuropsychologically—that automatically link to specific skill-focused interventions or curriculum-focused intervention programs/packages.

This means that most reading interventions need to be conceptualized as “controlled science experiments” that (a) are initially implemented in a “small-scale” way; (b) have clear short- and long-term criteria defining their success; (c) use formative and summative assessments that are sensitive to these criteria; and that (d) do not “scale-up” until the objective data validate their efficacy.

_ _ _ _ _

- Depending on the root cause analysis results, some students need skill-focused interventions—that focus on improving students’ literacy though the mastery of specific skills (e.g., how to decode specific phonemes, what specific words mean in different contexts or applications, how to answer specific types of comprehension questions, how to diagram the plot of a complex novel).

Other students need curriculum-focused interventions—that address students’ literacy gaps through an alternative or strategically-designed curriculum (e.g., Direct Instruction, Read Naturally, Leveled Literacy Instruction).

Still other students can benefit from computer-assisted instruction/intervention (e.g., Lexia, Passport Reading, Read 180).

Finally, some students need more intensive interventions—like Reading Recovery or the Orton-Gillingham approaches.

_ _ _ _ _

- The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) and other U.S. Department of Education-funded National Technical Assistance Centers have identified precious few literacy interventions that successfully remediate student deficits in the five recognized areas of reading.

Moreover, the different Practice Guides produced by the WWC are OK, but they don’t reveal any dramatic intervention suggestions for anyone who is knowledgeable in this area.

_ _ _ _ _

- Finally, there are some helpful intervention websites already developed. See, for example:

www.arstudentsuccess.org (Then link to the Literacy Intervention Matrix)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

Across the two Blogs in this Series, we discussed six essential interdependent blueprints that must be considered when “piecing together” a sound multi-tiered system of literacy instruction and supports.

These blueprints included the following:

- Blueprint 1: The Principles Underlying Effective Educational Policy

- Blueprint 2: A Psychoeducational Science-to-Practice Blueprint for Effective Literacy Instruction and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The seven flaws and ten scientifically-based practices that create an effective, comprehensive multi-tiered system of supports for literacy.

- Blueprint 3: Understanding the Instructional Environment and Its Contribution to Student Reading Proficiency

* Teacher/Instructional Factors

* Curriculum and Support Factors

* Student Learning and Mastery Factors

- Blueprint 4. The Data-based Problem-Solving Blueprint for Struggling and Failing Readers

- Blueprint 5. The Seven High-Hit Reasons Why Students Struggling or Fail in Reading

- Blueprint 6: The Multi-tiered Positive Academic Supports and Services Continuum

In this Part II, we went into considerable detail relative to Blueprints 4, 5, and 6.

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that Part II of this Blog Series has expanded on the most effective ways to conceptualize literacy instruction in our schools, and to address students who are underachieving, unresponsive, unsuccessful, disabled, and failing.

Clearly, this is a complex area of education.

But that’s the point. Too many are over-simplifying this complexity, and the result has been the continued failure of thousands of students who are graduating (or dropping out of) high school as functional illiterates.

I appreciate, as always, the time that you invest in reading these Blogs, and your dedication to your students, your colleagues, and the educational process.

Please feel free to send me your thoughts and questions.

And please know that—even during this time when many schools are closing due to the coronavirus pandemic—I am continuing to work with schools and districts across the country remotely and through video conference calls.

I would love to work with your school or district. Contact me at any time.

Best,