A New Federal Report Confirms that State Departments of Education are Trying, but Not Succeeding. . .

Twelve Essential School Improvement Questions Needed to Jump-Start the Process

Dear Colleague,

OK. . . full disclosure.

I consult all over the country helping districts and schools to successfully implement school improvement, multi-tiered services, positive behavioral support and school discipline systems, and interventions for academically struggling and behaviorally challenging students.

But I was also asked- - over 12 years ago- - to bring my evidence-based school improvement program and my years of experience to work at a state department of education level to help scale these approaches across a diverse state.

And so, while employed at the department of education level for a dozen years, I was simultaneously consulting in scores of other states at the preschool through high school (including alternative high school and residential treatment center) levels.

In contrasting the success of the school improvement initiatives that I partnered on- - at the department of education level versus at the consultation level- - I find, to a large degree, that I failed at the department of education level. . . while having very good success in my schools out-of-state.

Moreover, at the department of education level, I own my failures on behalf of the students, staff, schools, and districts where I worked. For example:

- I failed to keep up with the politics that put a revolving door at the top administrative echelons of the department of education.

- I failed to maintain positive and ongoing relationships with colleagues even though they were driven more by power, ambition, misplaced trust, insecurity, gaps in technical skill, or their own personal or professional agendas than by serving our students and schools.

- I failed because I believed that the science and practice of successful schools, and the reality that change occurs progressively over time would capture colleagues’ hearts, minds, commitments, and actions.

- I failed because “straight talk” is not always valued from an employee- - even though it is expected from an outside consultant.

- And, I failed to overcome the powerful influence of the federal government and its funded agendas that drove the state’s agenda and its practices.

But, even in the midst of these failures, it is interesting that many of my shortcomings at the department of education level were less apparent in the other states where I work. . . and this has allowed us to be successful there.

A New Federal Brief: “It Takes more than Money and Effort to Improve Under-performing Schools”

Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES) published an Evaluation Brief titled, State Capacity to Support School Turnaround.

The Brief’s purpose was to evaluate the impact of the $97.4 billion devoted to education (school improvement- - including the School Improvement Grant program- - was one of six funded areas) through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), and the $5.1 billion in additional Race-to-the-Top funds between 2009 and 2011, including $4.4 billion through ARRA.

The Brief investigated states’ capacity to support school turnaround as of Spring 2012 and Spring 2013 by looking at their expertise in supporting school turnaround processes in contrast to their commitments in this area. Based on interviews with administrators from 49 states and the District of Columbia, the Brief cited the following Key Findings:

- More than 80% of states made turning around low-performing schools a high priority, but at least 50% found it very difficult to turn around low-performing schools.

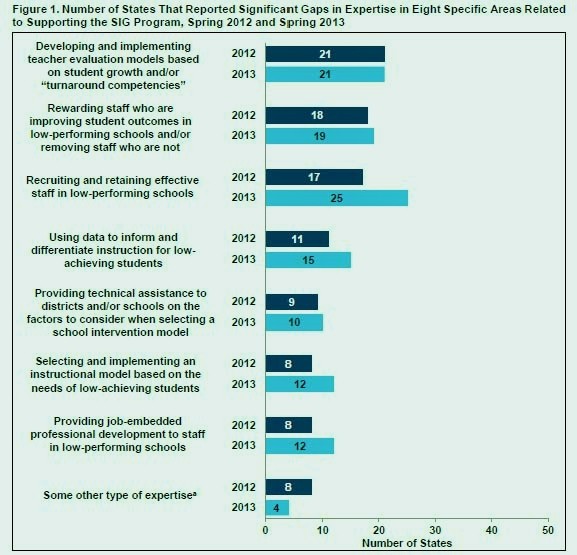

- 38 states (76%) reported significant gaps in expertise for supporting school turnaround in 2012, and that number increased to 40 (80%) in 2013.

- More than 85% of states reported using strategies to enhance their capacity to support school turnaround, with the use of outside resources decreasing over time and the use of internal organizational or administrative structures increasing over time.

Relative to the Brief’s second Key Finding above, the figure below shows the areas of expertise that the study investigated.

The Problem here is that in all of the areas evaluated, the Brief’s authors (a) did not assess what specifically was being implemented, and thus (b) it is impossible to determine what, causally, impacted specific student outcomes.

For example, what teacher evaluation and professional development models were evaluated? What instructional model, differentiated instruction approaches, and student outcome data were evaluated? And what teacher recruitment and retention criteria were used? And, for each of these, what were the functional components and activities implemented that directly affected student outcomes?

To again be honest: While it may appear that our state departments of education do not have a clue, the reality is that many states have made some progress in the areas covered by the Brief. For example, effective classroom instruction has been better defined and evaluated through systems like Danielson’s Framework for Teaching. And, new sets of academic standards (like the Common Core or other state-specific approaches) are refocusing teachers on how to design deeper modules and lessons, supported by more effective differentiated instruction.

BUT. . . there also are many areas where departments of education are conducting social experiments on students, staff, and schools. And, the reality is that when you go into the typical classroom in America (at any grade level), you rarely see the “bottom-up” evidence of our departments’ “top-down” efforts.

And then there is the “emperor’s clothes” effect. Who in their right mind thinks that a district superintendent is going demonstrate the “success” of a state initiative by bringing their state commissioner of education into a classroom to show him or her their unmotivated students and ineffective teachers? [Maybe our commissioners need to spend a week as “undercover bosses”?]

_ _ _ _ _

The Brief’s third Key Finding above was based on the states’ reports of their work with federally-supported centers or labs, universities, distinguished educators, other external organizations, and regional or country agencies. Here, between 2012 and 2013, the states reported using these outside resources less while increasing their internal capacity more. In fact, 46 states reported having some type of state-level structure in place for the 2012-2013 school year in contrast with just 25 states reporting such structures in 2007-2008.

The Problem here, however, is that most of structures created by the states related to establishing monitoring and reporting requirements, having contracts with external consultants, and creating state-level turn-around offices.

It is telling that the Report calls these “structures” because without the specific curricular, teacher/instructional, and student services, supports, programs, and interventions that directly relate to students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral success, these structures are just bureaucratic monoliths.

This is like constructing the outside structure of an office building without completing the inside rooms, wiring in electricity and other utilities, and moving in furniture and other amenities.

The Twelve Essential School Improvement Questions

So. . . what are the questions that all schools and districts need to ask (and answer now and over time) so that their structures are focused on supporting student learning, mastery, and “real-world” utility? We suggest the following for every school in a district:

The Student Learning and Mastery Questions

- Does every instructional staff person know the current functional skill level (mastery) of every student in the areas of literacy, math, oral expression, and written expression?

- Does every lesson, unit, class, and course identify the expected knowledge and understanding outcomes, and skill and application competence expected of students?

- Do all teachers and students know what the outcomes and competencies in #2 above look like, and how they will be accurately evaluated relative to formative learning and summative mastery?

- Does each lesson, unit, class, and course identify the prerequisite knowledge/content and skill/application competencies needed to effectively teach (and have students learn) its expected outcomes?

The Curriculum and Instruction Questions

- Do teachers have the curricular materials (direct and supplemental, course syllabi, class lessons) to effectively teach and differentiate?

- Are teachers working in cross/trans-curricular ways and teams so that they are consistently teaching and reinforcing common literacy, math, oral expression, and written expression skills?

- Can teachers differentiate instruction given the number of different skill levels of students in their classrooms?

- Do teachers understand and demonstrate the components of effective, differentiated instruction and universal designs for learning, and can they provide (or guide) classroom-based remediation, assistive supports, accommodations, and modifications when needed.

The Student-Staff Interaction Questions

- Do students take responsibility for their academic and social interactions and progress and that of their peers?

- Are students and staff taught and reinforced for their skill in the areas of organization, time and stress management, and ways to prioritize their learning and social, emotional, and behavioral actions and activities?

- Are students and staff taught and reinforced for interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention/resolution, and emotional coping skills?

- Are students and staff receiving the services, supports, strategies, and programs they need to be academically and interpersonally successful?

How do you Answer the Twelve Essential Questions ?

It would be nice to think that schools and districts have the data management systems, the ongoing evaluation processes, and the summer planning time to access and organize all of the data and information that can reliably and validly answer these questions. But, it is likely- - given the global nature of the top-down national and state guidance received over the past decade of “school reform”- - that these questions are new and (perhaps) intimidating.

And so, from a district perspective, here are some recommendations on how to start tackling these questions:

Recommendation 1. Identify the questions where you do have the data and information. Then, answer those questions, and organize your answers into an Action Plan that focuses- - during this coming school year- - on maintaining and strengthening your assets and successes, while addressing and eliminating your weaknesses and limitations. This Action Plan could become part of your district’s Strategic or annual Improvement Plan.

Critically, you should follow this suggestion even if you only have the data and information for specific grade levels, specific academic areas (e.g., literacy, math, science), and/or specific schools. If this is the case, then your Action Plan should identify the steps needed so that every school and all staff in your district will have the data to answer all of these questions in a timely way.

Recommendation 2. Identify the questions where data is missing or nonexistent. Then, decide which questions are the most important to answer during the coming school year. To do this, you will need to identify (a) for which questions is the relevant data and information easiest to collect and analyze, or (b) which questions are the biggest priorities relative to student outcomes.

For the Student Learning and Mastery Questions, understand that Question #1 is separate from Questions #2, 3, and 4- - which probably need to be answered together.

For the Curriculum and Instruction Questions, understand that Question #5 is a resource question; Question #6 is a planning and execution question; Question #7 is a data-based status question; and Question #7 is a teacher evaluation/professional development question.

Finally, for the Student-Staff Interaction Questions, understand that the district will need to prioritize and determine which question(s) here is(are) the most important to answer in the coming school year.

Significantly, from a strategic planning perspective, each district will need to decide how many questions to tackle in the coming year. This number will depend on the size and resources in the district, as well as the number of questions where data are missing. Regardless of the number of questions chosen, the goals, activities, timelines, and people involved in collecting the necessary data to answer the questions should be reflected, once again, in the district’s Strategic or annual Improvement Plan.

Recommendation 3. For all twelve of these questions- - regardless of the presence or absence of data- - the district may want to conduct one or more audits to more comprehensively assess its current status, needs, and directions. Among the possible audits are the following:

A Strategic Planning, District Leadership, Organizational Stability, and Systems-level Data Management Audit

A Recruitment, Retention, Professional Development, Coaching, Supervision, and Staff Evaluation Audit

An Academic Curriculum, Curricular Alignment, Effective Instruction, Progress Monitoring, Formative and Summative Assessment, and Classroom-based Academic Intervention and Support Audit

A Social, Emotional, and Behavioral/Health, Mental Health, and Wellness Instruction, Progress Monitoring, Formative and Summative Assessment, and Classroom-based Intervention Audit

A Multi-tiered Problem Solving, Consultation, and Instructional/Intervention Services, Supports, Strategies, and Programs Audit

A High Stakes Proficiency and College and Career Readiness Audit

Once again, it is unlikely that a district can accomplish all of these audits in one school year. Given this, districts will need to prioritize these audits, and create action plans so that they can be systematically, effectively, and collaboratively achieved. By embedding the Twelve Essential Questions into these audits, districts should be well on their way toward sustained school improvements that result in meaningful and functional student outcomes. Moreover, with good planning, these outcomes should more than satisfy any outcomes required at the state or federal level.

Summary

This most-recent IES Brief is consistent with and reinforces a plethora of federal studies and reports over the past two to three years that have concluded that the top-down school improvement approaches mandated or advocated by the federal, and many state, departments of education have not succeeded. Moreover, these reports suggest that the process is complex, money is not the sole solution, and a “one-size-fits-all” perspective does not work.

These reports also suggest that we are wasting time, effort, resources, and attention on global school improvement approaches, that have not been adequately field-tested, and that do not have the implementation specificity needed for success.

And because of this, we continue to lose students, staff, schools, and communities who are "turned off" to some the approaches that actually could work.

I believe that school improvement approaches must move to a more molecular level. We have got to ask the right questions, collect analyze the right data, and plan and execute in strategic and sustained ways. To do this, we need to look at the essential interdependent elements of school success- - the students, the curriculum, and the instruction. Moreover, we have got to work together- - effectively and efficiently- - to establish and institutionalize effective system, school, staff, and student approaches- -even if they involve sophisticated strategies and multiple layers.

Finally, we cannot be swayed by messages- - or messengers - - who want to oversimplify "school improvement" to the degree that success can never be attained. Critically, this will require more honesty, transparency, and candor from everyone. Indeed, we should not find out that 76% to 80% of our state departments of education report significant gaps in their school improvement expertise three years and more than $100 billion after the fact !!!

I hope that some of the ideas above resonate with you. Please accept my best wishes as many of you wind down your school years. If I can help your school(s) or district in any of the school improvement areas noted above, please do not hesitate to contact me. I appreciate the services and supports that you provide to all of your students.

Best,

Howie