Manipulating Policy, Buying Programs, and Following Federally-Funded Technical Assistance Centers Do Not Work

Why be Surprised. . . about Why We Aren’t Succeeding?

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

On April 4th, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities.

[CLICK HERE for Original Document.]

The Executive Study identified the rationale for the study reported in this document:

GAO was asked to review the use of discipline in schools. To provide insight into these issues, this report examines (1) patterns in disciplinary actions among public schools, (2) challenges selected school districts reported with student behavior and how they are approaching school discipline, and (3) actions Education and Justice have taken to identify and address disparities or discrimination in school discipline.

GAO analyzed discipline data from nearly all public schools for school year 2013-14 from Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection; interviewed federal and state officials, as well as officials from a total of 5 districts and 19 schools in California, Georgia, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Texas. We selected these districts based on disparities in suspensions for Black students, boys, or students with disabilities, and diversity in size and location.

The Executive Study then summarized the results:

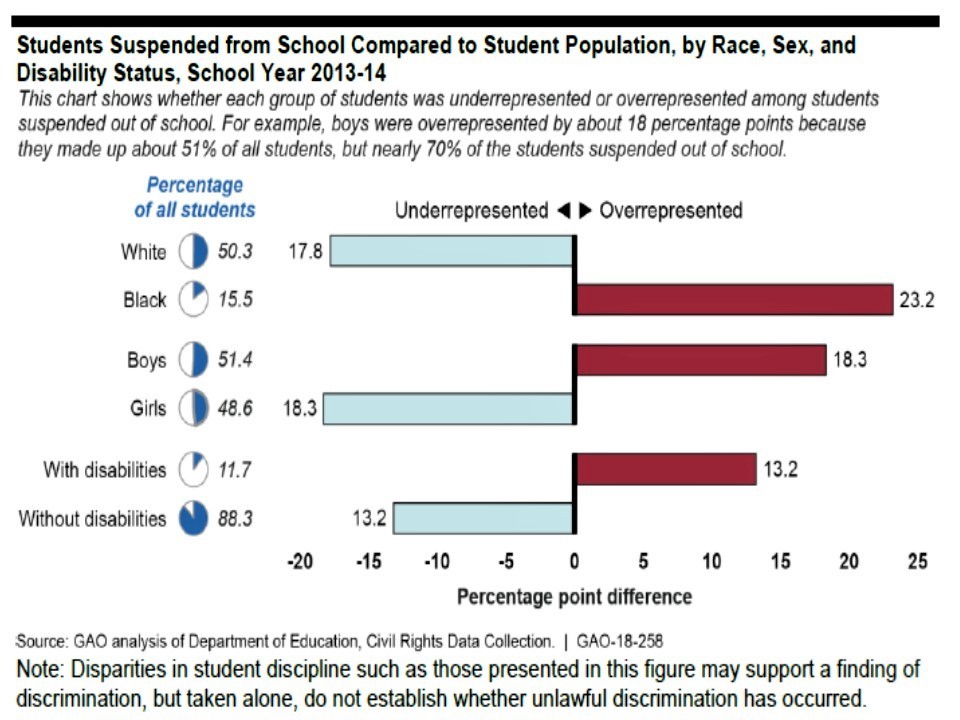

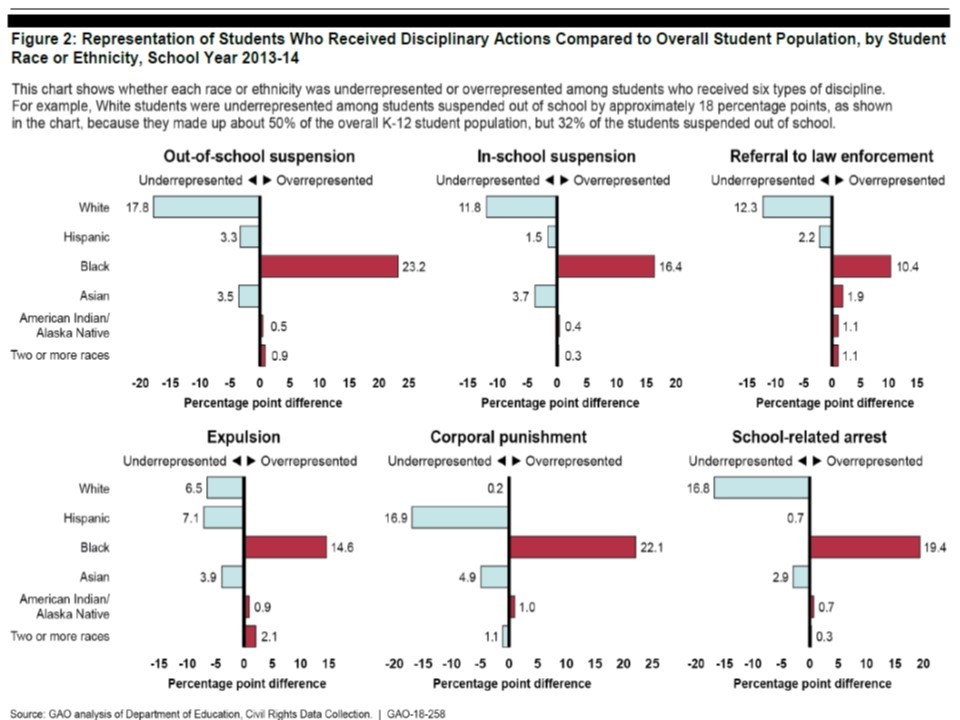

Black students, boys, and students with disabilities were disproportionately disciplined (e.g., suspensions and expulsions) in K-12 public schools, according to GAO’s analysis of Department of Education national civil rights data for school year 2013-14, the most recent available. These disparities were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended. For example, Black students accounted for 15.5% of all public school students, but represented about 39% of students suspended from school—an overrepresentation of about 23 percentage points (see Figures below).

Officials GAO interviewed in all five school districts in the five states GAO visited reported various challenges with addressing student behavior, and said they were considering new approaches to school discipline. They described a range of issues, some complex—such as the effects of poverty and mental health issues. For example, officials in four school districts described a growing trend of behavioral challenges related to mental health and trauma. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution for the issues that influence student behavior, officials from all five school districts GAO visited were implementing alternatives to disciplinary actions that remove children from the classroom, such as initiatives that promote positive behavioral expectations for students.

On the one hand: When you discuss this issue with educators working in the field, no one is surprised that so many of the national “efforts” to decrease disproportionate discipline referrals, suspensions, and expulsions over the past five-plus years have not worked.

That is because most previous and current efforts have avoided the underlying student- and staff-focused reasons for disproportionate referrals and actions.

Indeed, Representative Bobby Scott of Virginia (one of two U.S. Representatives who requested the GAO analysis) said, "The analysis shows that students of color suffer harsher discipline for lesser offenses than their white peers and that racial bias is a driver of discipline disparities."

This was true before, and it continues to be true today.

And it is not that bias and prejudice against, and sometimes fear of, African-American students are not some of the issues at-hand. But the primary reasons why we are not progressing in this area involve knowledge and training, resources and strategies, and consultation and accountability.

Indeed, during the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ interactions and reactions with African-American students, boys, and students with disabilities. . . reactions that, at times, are the reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals (when compared with the other groups in the Figures above).

And, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement involvement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

Instead, we have been tinkering around the edges—and in some cases, we have made the systemic problem worse.

_ _ _ _ _

On the other hand: While the GAO Report confirms that little has changed relative to disproportionality, it does not analyze the effectiveness of what the federal government has been doing through its national Technical Assistance Centers (TACs), over the past five-plus years, to change this state of affairs.

My point is that millions of our federal tax dollars have been invested in TACs over many years (for example, the national PBIS TA Center has been run by the same national directors out of the University of Oregon since 1997). . . and it does not appear that they have they accomplished their missions relative to the issues in and around disproportionality.

Instead, in Appendix III, the GAO Report cites all of these national TA Centers as “Key Federal Resources Related to Student Behavior and School Discipline.”

Are you kidding me?

While African-American students, boys, and students with disability are being held “accountable” for their classroom behavior, who is holding these TA Centers—disproportionately awarded to Universities and directed by University Professors— accountable?

And let’s not forget that most of these Universities receive a percentage of these grants (sometimes as high as 28% of the award) for “Indirect Costs” that typically help run, for example, their University Research Offices (so that they can secure more grants).

Moreover, let’s not forget that most of the University Grant Directors are researchers who, when they are testing their programs and strategies in the schools, often (a) select settings that have the highest probability of success, and (b) implement in “experimentally-pure” conditions that control the “real-life” variables that most practitioners face daily.

Thus, even when their programs and strategies have been “validated” (and the professors have written their publications and received their merit raises), they do not succeed under “real-world” conditions, because they have never been tested in those conditions.

_ _ _ _ _

For the record, the TA Centers cited in the GAO Report are:

U.S. Department of Education

National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments

National Student Attendance, Engagement, and Success Center

National Technical Assistance Center for the Education of Neglected or Delinquent Children and Youth

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports Technical Assistance Center

_ _ _ _ _

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Center for School Mental Health

National Center for Trauma-Informed Care and Alternatives to Seclusion and Restraint

National Child Traumatic Stress Network

National Resource Center for Mental Health Promotion and Youth Violence Prevention

Now Is the Time Technical Assistance Center

_ _ _ _ _

U.S. Department of Justice

School-Justice Partnership National Resource Center

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) National Training and Technical Assistance Center

_ _ _ _ _

My point here is NOT to cast dispersions.

My point is to caution educators in the field that we need to interview, question, and evaluate the field-based sensitivity, practicality, and functional outcomes of the work being done by these TA Centers. . . before we accept that they know what they are doing. . . and before we embrace and implement their approaches. . . relative to disproportionality, or anything else.

And, let’s remember: Many state departments of education, districts, and schools have implemented TA Center frameworks, programs, and strategies because these programs are free (even though they still use our federal tax dollars).

So, even though many of these frameworks and programs have not worked—across the vast majority of the districts and schools where they have been implemented—they have been widely distributed because school funding is so tight.

And in many cases when they did not work, they have exacerbated the original problems, and made students and staff more resistant to the next framework, program, or intervention.

And so, educators beware. Avoid the principle, “If it’s free, it’s for me.” Because there are no “free intervention lunches” in schools. If the framework or program does not work, there is a cost. . . and, sometimes, a heavy cost on students, staff, and schools.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Why the Disproportionality Outcomes Haven’t Changed

This is the first of a multi-Blog series addressing disproportionality within the prevention, strategic intervention, and intensive need/crisis management perspective of school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management.

During this series, we will address why current disproportionality efforts have not worked (this Blog’s primary focus), why specific approaches have not worked, the psychoeducational science underlying effective practice, and how to implement that practice.

For today, let’s review why most of the disproportionality “efforts” to date have not worked by exploring six primary flaws:

Flaw #1. Legislatures (and other “leaders”) are trying to change practices through policies.

Flaw #2. State Departments of Education (and other “leaders”) are promoting one-size-fits-all programs with “scientific” foundations that do not exist or are flawed.

Flaw #3. Districts and schools are implementing disproportionality “solutions” (Frameworks) that target conceptual constructs rather than teaching social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Flaw #4. Districts and Schools are not recognizing that Classroom Management and Teacher Training, Supervision, and Evaluation are Keys to Decreasing Disproportionality.

Flaw #5. Schools and Staff are trying to motivate students to change their behavior when they have not learned, mastered, or cannot apply the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed to succeed.

Flaw #6. Districts, Schools, and Staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services, supports, and interventions needed by students.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #1. Legislatures, State Departments of Education, and/or Superintendents (or other School Administrators) have changed policies that eliminate, for example, office discipline referrals (ODRs) or school suspensions for certain offenses for certain students, sometimes at certain ages.

These policy changes often have occurred without the input of instructional staff, without notice or preparation, without additional staff training or resources, and without field-testing for their effects and possible unintended consequences.

In many cases, these mandates have decreased the number of ODRs and school suspensions, but they have not changed either the disproportionality or some students’ inappropriate behaviors. In fact, in some settings, student behavior has gotten worse (because student consequences and accountability has been diminished), staff morale has plummeted, and classroom climate has been compromised.

[See my previous BLOG: From One Extreme to the Other: Changing School Policy from “Zero Tolerance” to “Total Tolerance Will Not Work. Decreasing Disproportionate Discipline Referrals and Suspensions Requires Changing Student and Staff Behavior. . . CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #2. State Departments of Education (and others) have promoted and/or districts and schools have purchased one-size-fits-all programs that have been not been independently and objectively implemented, evaluated, and proven effective in diverse school settings.

While we have already discussed this relative to many of the U.S. Department of Education-funded national TA Centers (see above), this situation has similarly occurred as publishers who also offer professional development, consulting conglomerates and “non-profit” foundations, and other independent consultants have flooded the “disproportionality market” with their theories, “scientifically-based research,” marketing and testimonials, and “foolproof” strategies.

[See my previous BLOG: Effective School-Wide Discipline Approaches: Avoiding Educational Bandwagons that Promise the Moon, Frustrate Staff, and Potentially Harm Students. . . CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _

To be sure, there are some great strategies and interventions out there.

But districts and schools need to separate the wheat from the chaff by independently evaluating (a) the science underlying the practices that are embedded in a “recommended” program; and then (b) whether the approaches that are scientifically-sound are relevant, applicable, and can be successfully applied and implemented with their students, staff, and schools.

[See my previous BLOG: “Scientifically based” versus “Evidence-based” versus “Research-based”: Why You Need to Know the History and Questions Behind these Terms. . . CLICK HERE]

_ _ _ _ _

In order to discriminate the wheat from the chaff, educators need to understand the differences between four sets of research-to-practice constructs:

* Frameworks versus Evidence-based Blueprints

* Correlational Programs versus Causal Practices

* Conscientious versus Convenience Research

* Meta-Analytic versus Method-Based Results

These are discussed below.

_ _ _ _ _

Frameworks versus Evidence-based Blueprints

“A framework is a menu where schools choose what they want to implement. An evidence-based blueprint is a roadmap where schools know where they are going and how they are going to get there.” (Knoff)

A framework is a menu of strategies and approaches where schools choose what they want to do, when, and with whom. Significantly, most schools make their menu choices based on the “low lying fruit”—what they “think” (but have not analyzed or confirmed) is the “problem,” what is easiest to solve or implement, or what they have resources for.

Frameworks rarely require an accurate assessment of the underlying reasons for the problems targeted, they use incomplete data-based problem-solving, and they do not implement strategies in the context of strategic planning. Often, framework interventions are not sustained over time, they do not solve the “real” problems, and they make the “true” problems worse or more resistant to change.

Two frameworks, sometimes used to address disproportionality, are Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS).

In contrast, an evidence-based blueprint is based on field-tested and validated science-to-practice principles and procedures. These blueprints are usually multi-tiered, they identify prerequisite conditions and needed resources, and they provide an implementation sequence where the essential components and strategies are specified. These blueprints most often rely on established, scientifically-based practices that are strategically integrated and implemented such that the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Districts and schools should choose valid and applicable evidence-based blueprints over frameworks.

_ _ _ _ _

Correlational Programs versus Causal Practices

“Correlational programs contribute to success. Causal programs make sure that success occurs.” (Knoff)

When new programs with multiple components, facets, and activities appear to be successful in a school that already has other initiatives, resources, and strategies, the most that anyone can conclude is that the new program may have contributed to the resulting success, but it could not have caused the success.

That is, unless the impact of the new program can be methodologically and empirically isolated from all of the other pre-existing initiatives, causality cannot be objectively proven.

And thus, in the complex real world of schools, most programs cannot claim the successes that they do.

Given the success scenario above, it is also possible that the program might not have contributed anything to the apparent successes. (This means that the other initiatives were the primary contributors.)

And, it is possible that the new program might have negatively impacted the successes. (This means that the pre-existing initiatives over-compensated for the new program’s failings.)

Finally, even when a new program contributes to a school’s success, it is virtually impossible to isolate and determine which of its many components, facets, and activities were most responsible.

_ _ _ _ _

This is not to discourage districts and schools from implementing integrated programs.

This is to warn districts and schools from accepting a program’s marketing or testimonial claims that it was causally responsible for cited student, staff, and school outcomes.

Said a different way: Because specific practices can be implemented in more methodologically-controlled and evaluated in more empirically-sound ways, it is more defensible to conclude that their results caused the successes that they report.

Once again, districts and schools are better served when they choose and implement evidence-based blueprints that consist of strategically-sequenced practices.

_ _ _ _ _

Conscientious versus Convenience Research

“Convenience research makes things easy for the researcher. Conscientious research makes things right.” (Knoff)

Educators at all levels (state, district, and school) need to be sound research consumers—independently evaluating programs, blueprints, and practices prior to selection and implementation.

This, once again, is discussed in my previous Blog:

“Scientifically based” versus “Evidence-based” versus “Research-based”—Why You Need to Know the History and Questions Behind these Terms”

Indeed, when considering a program, state, district, and school leaders need to use (or contract with) professionals who are well-trained and expert in research design and statistical analysis—asking them to review the studies that program developers cite as evidence that their approach “worked.”

More specifically, these professionals should analyze the quality and generalizability of each study’s (a) student and staff participants; (b) research design and data collection methods; (c) statistical analyses and results; and (d) conclusions and implications.

Too often, the studies cited by program developers have been designed and implemented by convenience—rather than through conscientious planning, execution, and analysis.

Convenience studies cannot be used to validate a program or practice. Moreover, if the data from any study are not reliable and/or valid, then any program-related claims of success and efficacy are null and void.

_ _ _ _ _

Meta-Analytic versus Single-Study Research

“Meta-analytic research identifies what to do. Single-study research identifies how to do it.” (Knoff)

In their quest for scientifically-based strategies, approaches, practices, or interventions, districts and schools need to discriminate between meta-analytic studies and single-study research.

Briefly, a meta-analytic study uses a statistical procedure that combines the effect sizes from many different single research studies that have investigated the same (or a common) strategy, approach, practice, or intervention. This procedure results in a pooled effect size that provides a more reliable and valid “picture” of the strategy or intervention’s usefulness or impact, because it involves more subjects, more implementation trials and sites, and (usually) more geographic and demographic diversity. Typically, an effect size of 0.40 is used as the “cut-score” where effect sizes above 0.40 reflect a “meaningful” impact.

While meta-analytic results are powerful, districts and schools must still determine whether the individual studies in a meta-analysis all used the same implementation methods and steps—before adopting and implementing a specific approach. This is because most meta-analytic studies include single studies that use somewhat different methods and steps even though their approaches are broadly similar.

Thus, in order for a meta-analytic result to be useful, educators need to know exactly what specific methods and steps must be implemented to replicate the results in their district or schools.

For example, according to John Hattie’s meta-analytic research, the factor that most strongly relates to student achievement is “collective teacher efficacy.” But “collective teacher efficacy” is a construct that involves many different teacher interactions and behaviors.

If a district or school wants to improve its “collective teacher efficacy,” it will need to review the individual studies that were statistically analyzed together, and identify the teacher interactions and behaviors that were most-responsible for the strong effect size result.

_ _ _ _ _

A single-study result is generated from one (hopefully) well-designed, executed, and analyzed study of a specific strategy, approach, practice, or intervention.

In contrast to meta-analytic studies, well-designed single-study research typically has a clearly-described method and steps that can be directly (perhaps, with minor modifications) implementation by a district or school.

_ _ _ _ _

Once again, districts and schools need to have their best-trained professionals evaluating both meta-analytic and single-study publications. But once the “best” studies have been identified, the differences between these two research approaches—as discussed above—must be recognized and understood.

This is particularly important in this “Era of Hattie.”

John Hattie has made an unbelievable series of contributions to our understanding of student achievement—through his meta-analytic research. But too many districts and schools are taking his results “at face value,” assuming that they know how to implement the strategies and approaches that are embedded in many of his broad-based factors.

And critically, Hattie has not specifically analyzed the research related to disproportionality, although some may try to apply some of his meta-analytic results to this area.

We have discussed the meta-analytic versus single-study research issue more completely in a previous Blog, Hattie’s Meta-Analysis Madness: The Method is Missing! Why Hattie’s Research is a Start-Point, but NOT the End-Game for Effective Schools.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #3. Districts and schools are implementing disproportionality “solutions” (Frameworks) that target conceptual constructs rather than teaching social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

“You can’t teach a construct, you have to teach behaviors and skills.” (Knoff)

As some schools try to combat disproportionality by improving student behavior (which is a good idea), some are using programs that focus on students’ character or their social-emotional learning—rather than practices that focus on behaviors and skills.

Take character education programs.

In general, the vast majority of character education programs are not evidence-based, and they do not help schools to attain the outcomes that they most want—a decrease in inappropriate student behavior, and an increase in appropriate, prosocial student behavior.

This is because most character education programs only (a) increase students’ awareness of appropriate and inappropriate behavior (see Flaw #4 below); and (b) they often only talk about behavior (through stories, discussions, and group work).

That is, most character education programs do not behaviorally teach behavior (like the plays that a basketball team performs on the court, or the scenes that a theatre group performs on stage) using a sound scientifically-based pedagogical approach.

Indeed, to be successful, Behavioral Instruction must include the following:

* Teach the steps/scripts and behaviors for the skills;

* Model or demonstrate the scripts and the behaviors;

* Have the students Role-Play or practice (with explicit, critical feedback) the scripts and the behaviors;

* Transfer the practice of the behaviors (with continued supervision and feedback) into progressively more challenging real-life simulations, settings, and situations;

* Use teachable, real-life moments to infuse the behaviors into real-life settings and situations; and

* Continue the practice and infusion until the behaviors are conditioned, automatic, and at a social, emotional, and behavioral level of self-management.

_ _ _ _ _

But another critical reason that programs focusing on character and social-emotional learning do not change student behavior is that they focus their “instruction” on global constructs or character traits—once again, rather than behavior.

For example, a popular character education program, Character Counts, teaches six pillars of character: Trustworthiness, Respect, Responsibility, Fairness, Caring, and Citizenship.

The point here is that: None of these constructs can be taught.

In order to teach these constructs, teachers would have to agree on the specific behaviors inherent in each construct, match it to the age and developmental level of their

Said a different way: Teachers cannot teach Trustworthiness; they need to teach the specific behaviors that represent the construct of Trustworthiness. Teachers cannot teach Respect; they need to teach the behaviors of Respect. etc. . . . etc.

Beyond this, from an instructional perspective, you can have all of the Classroom Meetings and Monthly Celebration Assemblies that you want.

Talk does not change behavior. Only behavioral instruction changes behavior.

When Character Counts (and other character education programs) “work”—they are actually only working with the students who already had the social skills. For the students who are disproportionately sent to the Office for discipline, they do not have the skills.

That’s why they need social, emotional, and behavioral skill instruction, and why Character Counts will not work with them.

For more information in this area, feel free to read our previous Blog:

When Character Education Programs Do Not Work: Creating “Awareness” Does NOT CHANGE “Behavior” . . . TEACHING Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skills Requires Behavioral Instruction

_ _ _ _ _

Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)—advocated and led by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)—also talks in constructs, and not behaviors.

Indeed, below are the constructs that CASEL specifically targets as its primary SEL outcomes:

SELF AWARENESS

* Labeling one’s feelings

* Relating feelings and thoughts to behavior

* Accurate self-assessment of strengths/challenges

* Self-efficacy

* Optimism

_ _ _ _ _

SELF MANAGEMENT

* Regulating one’s emotions

* Managing stress

* Self-control

* Self-motivation

* Setting and achieving goals

_ _ _ _ _

SOCIAL AWARENESS

* Perspective-taking

* Empathy

* Appreciating diversity

* Understanding social and ethical norms for behavior

* Recognizing family, school and community supports

_ _ _ _ _

RELATIONSHIP SKILLS

* Building relationships with diverse individuals/groups

* Communicating clearly

* Working cooperatively

* Resolving conflicts

* Seeking help

_ _ _ _ _

RESPONSIBLE DECISION MAKING

* Considering the well-being of self and others

* Recognizing one’s responsibility to behave ethically

* Basing decisions on safety, social and ethical considerations

* Evaluating realistic consequences of various actions

* Making constructive, safe choices about self, relationships and school

_ _ _ _ _

As is evident from this list, none of these SEL outcomes are directly observable, measurable, or behaviorally-specific.

Thus, like a character education program, districts and schools will need to operationalize and create approaches to teach the behaviors that they want to target within each of the constructs above.

This creates the potential that schools and teachers will not use the Behavioral Instruction steps outlined above, that the instruction will be inconsistent across teachers—even at the same grade-levels, and that students will not learn the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed.

_ _ _ _ _

But CASEL has also publicly stated that (a) SEL is a framework (see Flaw #2); (b) it will not advocate a specific model with implementation blueprints, components, activities, and steps; and (c) districts and schools will need to figure out how they are going to help students increase their capacities in the construct areas above.

Given this, for any “successful” SEL districts or schools, we cannot automatically say that their success was due to SEL, nor can we conclude that SEL is a successful approach. This is because most schools will be implementing different SEL activities, and their results are correlational and not causal.

Moreover, until we know what a “successful” school did—relative to its specific “SEL” (a) goals, outcomes, and criteria of success; (b) methods, strategies, training, and implementation; (c) evaluation, measurement, and statistical analyses—we will not be able to transfer and replicate their “success” to another school.

Parenthetically, CASEL has historically gone from a small research group based in Chicago, to a political-powered movement in the U.S. Congress--especially courtesy of funding from the NoVo Foundation—led by Warren Buffett’s daughter and son-in-law.

Districts and schools need to be mindful of this political influence, and focus on the science-to-practice components needed by all social, emotional, and behavioral approaches in order to have student-centered success.

This science-to-practice perspective is what has been missing from the approaches trying to positively impact the students who have been disproportionately referred and suspended for disciplinary offenses.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #4. Districts and Schools are not recognizing that Classroom Management and Teacher Training, Supervision, and Evaluation are Keys to Decreasing Disproportionality

In January 2014, the National Council on Teacher Quality published Training our Future Teachers: Classroom Management.

After an extensive review of the classroom management research, five strategies were identified as ones that university programs should focus on during teacher training:

* Rules: Establish and teach classroom rules to communicate expectations for behavior.

* Routines: Build structure and establish routines to help guide students in a wide variety of situations.

* Praise: Reinforce positive behavior using praise and other means.

* Misbehavior: Consistently impose consequences for misbehavior.

* Engagement: Foster and maintain student engagement by teaching interesting lessons that include opportunities for active student participation.

_ _ _ _ _

The study went on to examine the professional sequences within 122 teacher preparation programs, including their lecture schedules, teacher candidate assignments, practice opportunities, observation and feedback instruments, and textbooks.

The Report then concluded:

* Most programs can correctly claim to cover classroom management, with only a tiny fraction (

* Most teacher preparation programs do not draw from research when deciding which classroom management strategies are most likely to be effective and therefore taught and practiced. Especially out of favor seem to be strategies that impose consistent consequences for misbehavior, foster student engagement, and—most markedly—use praise and other means to reinforce positive behavior. Half of all programs ask candidates to develop their own “personal philosophy of classroom management,” as if this were a matter of personal preference.

* Instruction is generally divorced from practice (and vice versa) in most programs, with little evidence that what gets taught gets practiced. Only one-third of programs require the practice of classroom management skills as they are learned. This disconnect extends to the student teaching experience.

* Contrary to the claims of some teacher educators, effective training in classroom management cannot be embedded throughout teacher preparation programs. Our intensive analysis of programs in which classroom management is addressed in multiple courses reveals far too great a degree of incoherence in what teacher candidates learn and what they are expected to do in PK-12 classroom settings. Embedding training everywhere is a recipe for having effective training nowhere.

_ _ _ _ _

In our experience, virtually nothing has changed in the four years since the publication of this Report, and most districts and schools are not providing the new-teacher training, supervision, and support—specifically in classroom management—that is needed by their new classroom teacher recruits. That is, districts still favor professional development in curriculum development and academic instruction and intervention in their teacher induction programs over comprehensive training and evaluation in classroom management.

Moreover, while classroom management is embedded in many of the evaluation systems for all teachers (e.g., Danielson), many districts have either taken these items out of these evaluation systems, or they differentially weight these items below those items focusing, once again, on academic instruction and student learning outcomes.

_ _ _ _ _

The point here is that one of the root causes of disproportionality is poor classroom management. In order to comprehensively address this problem, districts and schools (and teacher training programs) are going to have to systematically increase and improve their basic classroom management training, mentoring, supervision, evaluation, and teacher accountability systems.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #5. Schools and Staff are trying to motivate students to change their behavior when they have not learned, mastered, or cannot apply the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed to succeed.

“You can’t motivate a student out of a skill deficit.” (Knoff)

One of the biggest national “pushes” to address Disproportionality over the past few years has been “Restorative Practices.” But it is hard to know what “Restorative Practices” are—as they are a collection of strategies—and there is no sound science-to-practice research that has validated how these strategies should be integrated, sequenced, or evaluated.

Moreover, the Restorative Practice “push” has fostered a “cottage industry” of organizations and vendors who similarly have not independently or objectively validated their approaches using sound research.

In the words of an Issue Brief (“Restorative Practices: Approaches at the Intersection of School Discipline and School Mental Health”) published by the Now Is the Time Technical Assistance Center, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration:

Restorative practices, a diverse and multitiered set of classroom and school-based strategies (all bolded words are my emphasis) that emphasize the importance of the relational needs of the community in fostering student accountability for behavior, have piqued the interest of educators and school-based Mental health providers alike. Interest across child-serving personnel has been stoked by emerging evidence that restorative practices reduce exclusionary discipline practices while also improving students’ social and emotional well-being and school connectedness.

Large-scale, rigorous research on the effects of restorative practices on school-related outcomes is underway and results are forthcoming. In the meantime, promising results are being reported from school districts across the United States.

Restorative practices are founded upon the conceptthat both individuals and relationships must heal afterharm occurs in the school community. With rootsin indigenous and Mennonite cultures, restorativepractices uphold the concept that humans are socialand communal and need to learn and grow throughrelationship and community. The philosophy (not science; my addition) behindrestorative practices acknowledges that children andyoung people who are involved in bullying, violence,and school disruptions are themselves feelingunsafe and in need of an opportunity to reattachand re-engage.

Restorative practices are based on the premise that individuals and/or groups in conflict benefit from working together to find resolutions and repair the resultant damage caused to their relationship.Restorative practices focus on the relationshipbetween the perpetrator of the “crime” (i.e., incidentrequiring disciplinary response) and members of theschool community, including victims, bystanders, andtheir families. Restorative practices are designedto open up dialogue, give everyone an opportunityto be heard, and allow those impacted by harm todetermine resolutions collaboratively.

Several types of Restorative Practices exist,including: restorative justice, communityconferencing, community services, peer juries, circle processes, conflict prevention and resolution programs informal restorative practices, and social-emotionallearning. Although Restorative Practices are diverse in nature, they are all designed for the same set of purposes: to repair relationships and trust, as opposed to distribute retribution or punishment; to improve of all parties in conflict resolution using fair practices; and to improve the social fabric of the school by sharing views and experiences and developing empathy for others in the school community.

_ _ _ _ _

Thus, while Restorative Practices are being advocated, once again, by a federally-funded national Technical Assistance Center, this official Issue Brief appears to be emphasizing that (a) these practices have not yet been validated; (b) no empirically-validated decision-making process has been established to determine which practices are most successful under specific circumstances; and (c) any use of these practices is premature.

In addition, according to the Issue Brief:

* Restorative practices are based more on philosophy than evidence-based practice.

* As with any framework, when a district or school claims that “Restorative Practices” have worked, we need to know exactly what approaches they used, and even then, they have to demonstrate that these approaches caused (as opposed to contributed) to the perceived success.

* Restorative practices depend on the students involved wanting to “work together to find resolutions and repair the resultant damage caused to their relationship.” In our experience, some victims (both the aggressors and the victims) do not believe or want a resolution.

* Restorative practices are not preventative. That is, they occur after an inappropriate behavior, disciplinary offense, or anti-social action has occurred.

* Finally, Restorative Practice are consequential in nature, and they are focused on holding students accountable for their inappropriate behavior. If students have not learned and mastered the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and/or emotional control and coping skill gaps that have caused the inappropriate behavior, no amount of restoration is going to prevent future inappropriate behavior from re-occurring.

We have discussed many of these issues in a previous Blog:

Restorative Practices and Reducing Suspensions: The Numbers Just Don’t Add Up

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Flaw #6. Districts, Schools, and Staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services, supports, and interventions needed by students.

As noted earlier in this discussion, disproportionate disciplinary referrals and actions (like suspensions) for minority (largely, African-American) students and students with disabilities occur due to a combination of (a) district policy and procedures; (b) teacher and administrator interactions, reactions, and decisions; and (c) student behavior.

In the latter area, administrators and staff need to discriminate between inappropriate student behavior that is disciplinary in nature versus due to psychoeducational factors. While this is not always easy, and both elements could be present, this discrimination is critical to coming up with a plan to change students’ inappropriate behavior—the ultimate goal of any action or response.

Quite simply, a discipline problem typically occurs where a student can demonstrate appropriate behavior but chooses not to.

In other words, the student is somehow internally motivated (e.g., due to needs related to attention, control, revenge, anger) to “make a bad choice,” or is externally motivated (e.g., by peer pressure or reinforcement, to escape from failure or frustration) to make the same bad choice.

From a cognitive-behavioral psychology perspective, teachers or administrators are “banking” on the fact that their disciplinary consequences are powerful enough to motivate a student to “make a good choice” the next time, and that the resulting positive rewards will maintain the appropriate behavior.

Thus, disciplinary actions need to have flexible and available consequences that are meaningful and powerful enough to motivate behavioral change.

At the same time, school principals still need to have “administrative actions” available when student behavior is grossly antisocial or dangerous. Critically, these administrative actions rarely motivate students to change their behavior.

_ _ _ _ _

In contrast, a psychoeducational problem typically occurs when a student has not learned or learned to apply interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention or resolution, or emotional control and coping skills. These are skill deficits, and they require skill instruction to facilitate change.

In fact, for some students, some of these skill deficits are related to fairly significant social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health issues . . . issues that require strategic or intensive intervention—including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Critically, you can’t motivate a student out of a skill deficit. That is, no amount of consequences or administrative actions will change skill these deficits—they require instruction and/or psychological intervention.

_ _ _ _ _

In order to discriminate between disciplinary- and psychoeducationally-based behavioral problems, administrators may need to ask relevant members of their Student Assistance Team (or the equivalent) to complete functional, behavioral, and/or psychological assessments. Based on the assessment results, the Team can then recommend, and facilitate the implementation of, teacher and classroom-based behavioral interventions, and student-centered social, emotional, and/or behavioral interventions.

In order to accomplish this, every district should have a comprehensive multi-tiered system of supports that includes the professional development needed by all teachers and administrators (e.g., in classroom management, engagement and de-escalation techniques, classroom-based behavioral interventions). This multi-tiered system also should include related services professionals (e.g., counselors, school psychologists, social workers) who have the behavioral assessment and strategic interventions skills (and time) to address students’ more intensive or complex psychoeducational needs.

But the reality is that most districts and schools do not have these systems or professionals in place.

And, at times, the systems are being guided by national models that have significant flaws. These flaws, and effective practice alternatives, have been previously discussed in the following Blogs:

Improving Student Outcomes When Your State Department of Education Has Adopted the Failed National MTSS and PBIS Frameworks: Effective and Defensible Multi-Tiered and Positive Behavioral Support Approaches that State Departments of Education Will Approve and Fund (Part I of II)

_ _ _ _ _

Improving Student Outcomes When Your State Department of Education Has Adopted the Failed National MTSS and PBIS Frameworks: Effective Research-to-Practice Multi-Tiered Approaches that Facilitate All Students' Success (Part II of II)

_ _ _ _ _

The Endrew F. Decision Re-Defines a “Free Appropriate Public Education" (FAPE) for Students with Disabilities: A Multi-Tiered School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management Model to Guide Your FAPE (and even Disproportionality) Decisions (Part III)

_ _ _ _ _

If we are going to successfully address the issue of Disproportionality in our schools, it will be through the strength of our comprehensive, multi-tiered systems of services, supports, strategies, and interventions.

Clearly, policy-level changes and mandates have not solved this problem. It is now time to apply evidence-based practices that will not only solve the problem, but make students, staff, and schools more productive, safe, and successful.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

The recent U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities, clearly demonstrates that disproportionality in our schools continues to exist—even in the face of policy changes at the state and district levels, and program adoptions at the district and school levels.

While this Report provides considerable data, it does not analyze the effectiveness of what the federal government has been doing through its national Technical Assistance Centers (TACs), over the past five-plus years, to change this state of affairs.

In fact, despite the fact that many of the TAC frameworks and program recommendations are flawed, the Report actually cites them as available resources for states, districts, and schools.

We have been unsuccessful in addressing the issue of disproportionality in our schools because most previous and current efforts have avoided analyzing the underlying student- and staff-focused reasons for this problem.

In fact, during the past ten-plus years of trying to systemically decrease disproportionality in schools, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, and we have not linked these root causes to strategically-applied multi-tiered science-to-practice strategies and interventions that are effectively and equitably used by teachers and administrators.

Moreover, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of staff members’ interactions and reactions with African-American students, boys, and students with disabilities. . . reactions that, at times, are the reasons for some disproportionate Office Discipline Referrals (when compared with the other groups in the Figures above).

And, we have not comprehensively and objectively identified and addressed the root causes of administrators’ disproportionate decisions with these students as they relate to suspensions, expulsions, law enforcement involvement, and referrals to alternative school programs.

This first Blog in this series addressed why current disproportionality efforts have not worked and why specific approaches have not worked. The next Blog will address the psychoeducational science underlying effective practice and how to implement that practice.

_ _ _ _ _

I appreciate everything that you do to support our students and colleagues in the field. My Blog analyses and comments are not designed or motivated to emphasize what is not working in our field. Instead, they are designed to critique why some things are not working, and to provide field-tested, science-to-practice alternatives.

Relative to these alternatives:

Additional research and practice support in the areas discussed in this Blog can be found on my brand-new website where all of my electronic books have been updated to reflect the new Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and the newest research and practices in our field.

Meanwhile, I always look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any of the multi-tiered areas discussed in this message, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

As the “testing season” continues in most of our schools nationwide, please accept my best wishes.

Best,