What State Departments of Education Need to Learn If Using PBIS to “Solve” This Problem

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

The number of seclusions and restraints in our nation’s schools—whether involving general education students or students with disabilities (who are disproportionately represented in these events)—is a national tragedy and embarrassment. This problem must be solved.

But the resolution must be multi-layered. While, top-down, it may require federal and/or state legislation, it eventually must be, bottom-up, functionally addressed in our schools as part of an effective multi-tiered system of supports and interventions.

And if Congress or state legislatures get involved, they must have accurately, differentiated, and well-analyzed data. This is because much of the current data have gaps, do not differentiate different student groups in meaningful ways, and have not been analyzed to determine the root causes of the behavioral situations that result in student seclusions and restraints.

The need for accurate, differentiated, and well-analyzed data is particularly important at the present time. Indeed, in mid-January (2019), the U.S. Department of Education’s Offices for Civil Rights (OCR) and Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) announced an initiative to “address the inappropriate use of restraint and seclusion” on students with disabilities. OCR and OSERS plans to attend to three specific areas: (a) Increasing the number of compliance reviews in districts across the country; (b) Disseminating more legal and intervention resources focused on prevention and alternative responses; and (c) Improving the integrity of incident reporting and data collection.

Then, on February 27, 2019, an education subcommittee of the House of Representatives conducted a hearing where the number of seclusions and restraints across the country was updated, possible alternative approaches were outlined, and the role of the federal government in decreasing seclusions and restraints was discussed.

During this hearing, the U.S. Department of Education once again promoted George Sugai’s testimony. Sugai has been the Co-Director of the National Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) Technical Assistance (TA) Center since its inception in 1997. This, and others’ testimony during this meeting, once again reinforced the point above—that comprehensive analyses of the root causes of the seclusion and restraint dilemma in our schools are not being presented to policymakers. In fact, in some cases, Congress only hears what the U.S. Department of Education (and other federal agencies) want it to hear.

Indeed, over the years, he (or his Co-Director colleague) are present any time Congress has a hearing on a significant social, emotional, behavioral, disciplinary, or related school crisis hearing. This allows the U.S. Department of Education (and specifically, its Office of Special Education Programs—OSEP) to use its “bully pulpit” to singularly advocate their PBIS framework—a framework that has not been successful, and that has significant science-to-practice gaps.

This last statement has been documented in numerous past Blogs:

October 7, 2017 Improving Student Outcomes When Your State Department of Education Has Adopted the Failed National MTSS and PBIS Frameworks: Effective and Defensible Multi-Tiered and Positive Behavioral Support Approaches that State Departments of Education Will Approve and Fund (Part I of II)

_ _ _ _ _

October 21, 2017 Improving Student Outcomes When Your State Department of Education Has Adopted the Failed National MTSS and PBIS Frameworks: Effective Research-to-Practice Multi-Tiered Approaches that Facilitate All Students' Success (Part II of II)

_ _ _ _ _

February 16, 2019 Redesigning Multi-Tiered Services in Schools: Redefining the Tiers and the Difference between Services and Interventions

_ _ _ _ _

Following up on the February education subcommittee hearing, it is expected that Congressional Democrats will soon introduce legislation to ban the use of isolation and seclusion in schools, and to put major restrictions on physical restraints.

This two-part Blog series was written to try to get a more accurate picture of the current status of why seclusions and restraints occur in schools, and to present a “roadmap” of how to functionally and successfully begin to address the issues.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Review of Part I of this Two-Part Series

In Part I of this Blog, the following areas were discussed:

- The definitions of seclusion and restraints

- The historical and current incident levels of these actions in schools

- The U.S. Department of Education’s formal attention to this issue since 2009

- The U.S. Department of Education’s faulty advocacy of the PBIS framework as a solution to this problem

[CLICK HERE for Part I]

Here is a brief recap.

_ _ _ _ _

The Definition and Current Incident Levels of Seclusion and Restraint

The Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) is an ongoing U.S. Office of Civil Rights survey involving all public schools and school districts in the United States. Initiated in 1968, the CRDC measures student access to courses, programs, staff, and other resources and issues that impact education equity and opportunity for students across the country.

In the May, 2012 U.S. Department of Education’s Restraint and Seclusion: Resource Document, the following CRDC definitions were documented:

The CRDC defines seclusion as:

The involuntary confinement of a student alone in a room or area from which the student is physically prevented from leaving. It does not include a timeout, which is a behavior management technique that is part of an approved program, involves the monitored separation of the student in a non-locked setting, and is implemented for the purpose of calming.

The CRDC defines physical restraint as:

A personal restriction that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a student to move his or her torso, arms, legs, or head freely. The term physical restraint does not include a physical escort.

Physical escort means a temporary touching or holding of the hand, wrist, arm, shoulder, or back for the purpose of inducing a student who is acting out to walk to a safe location.

_ _ _ _ _

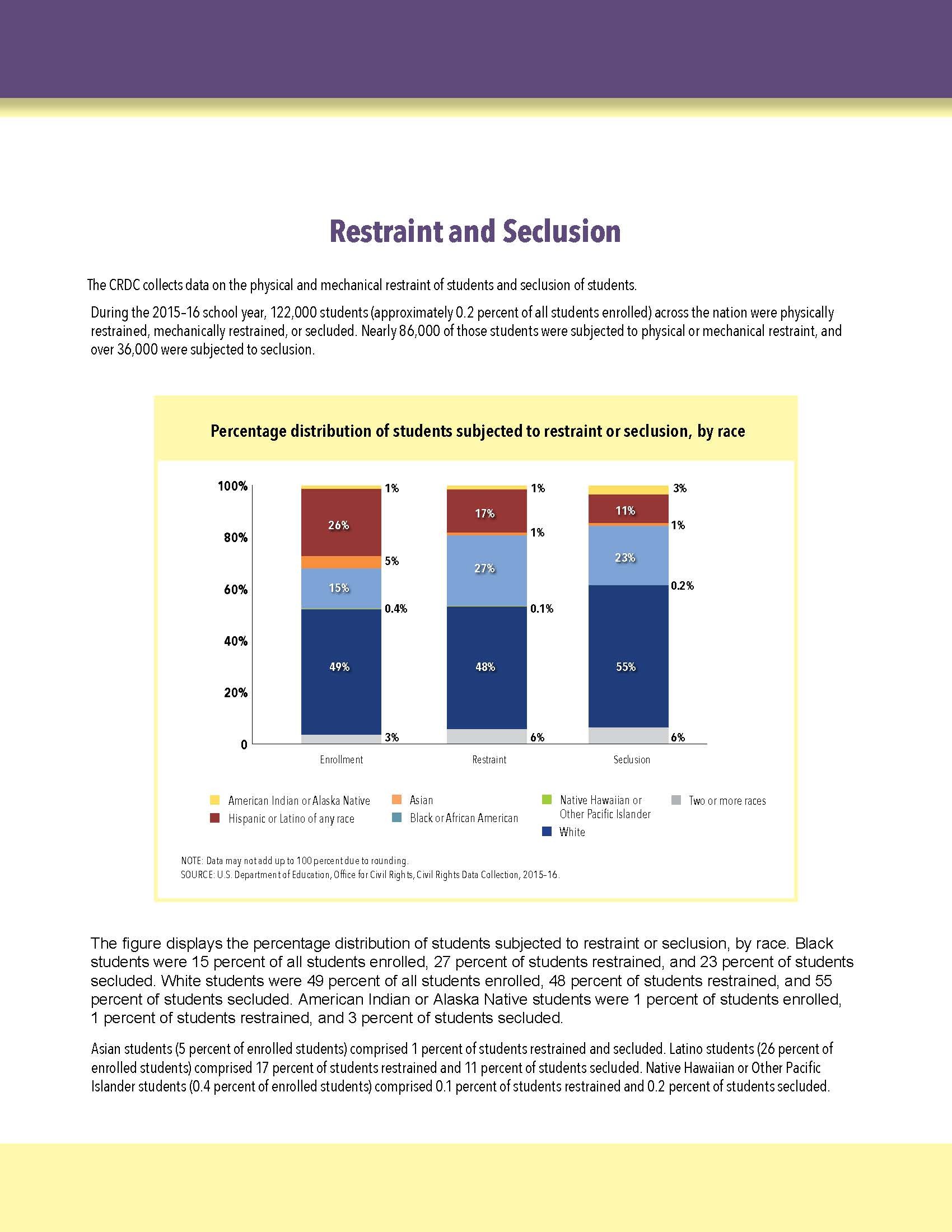

On April 24, 2018, the CRDC released its Report for the 2015-2016 school year. The Report summarized the experiences of more than 50.6 million students at over 96,000 public schools across the country, and it included the following seclusion and restraint data.

During the 2015-2016 school year:

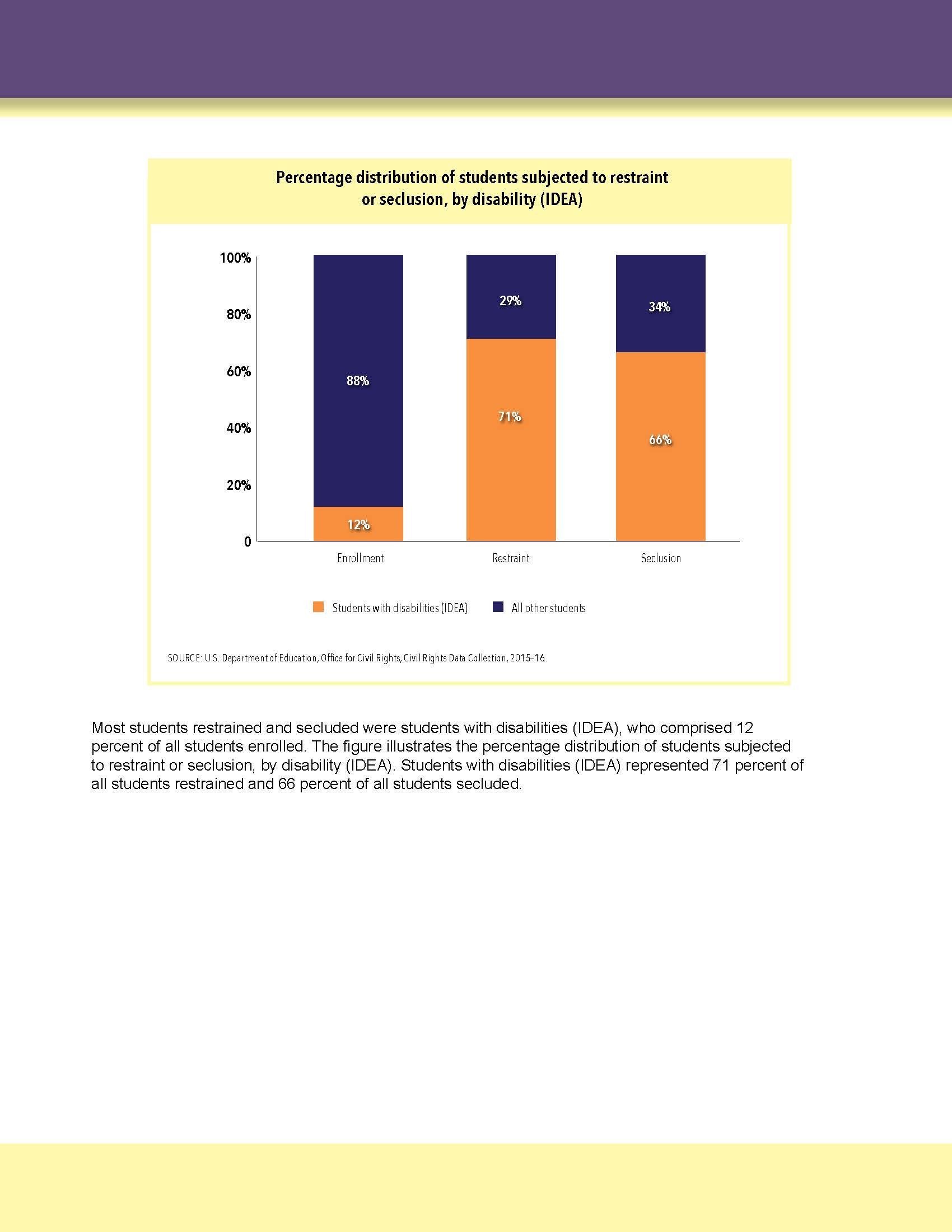

- Over 84,000 students covered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act were restrained or secluded in 2015-16 (69% of the more than 122,000 students restrained or secluded nationally).

- 23,760 students with disabilities were secluded (66% of the 36,000+ seclusions for all students across the country).

- 61,060 students with disabilities were restrained (71% of the 86,000+ restraints for all students across the country).

- 1.3 of every 100 students with disabilities nationally was restrained or secluded.

Below are two figures that show these important data.

_ _ _ _ _ _

The U.S. Department of Education and the PBIS Framework

Part I of this two-part Blog also provided an historical account of how the U.S. Department of Education—especially during the Arne Duncan years—explicitly singled out the National PBIS TA Center’s PBIS framework. This started in the first months of the Obama presidency (February, 2009) as the Administration dedicated $117 billion to education as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). In announcing the funding to the educational community, Secretary Duncan singled out the PBIS framework as available for ARRA funding.

A few months later, after the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report (May 19, 2009) which was directly addressed by Secretary Duncan in a July 31, 2009 letter to the Chief State School Officers across the county. Once again, Duncan singled out the PBIS framework, saying:

My home State of Illinois has what I believe to be one good approach, including both a strong focus upon Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) as well as State regulations that limit the use of seclusion and restraint under most circumstances. . .

. . . The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provides significant one-time resources that districts can use to implement a school-wide system of PBIS. Districts could, consistent with program requirements, use funds provided for the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and State and local funds to provide professional development, develop data systems, and offer coaching to establish and sustain these programs. The Department’s Office of Special Education Programs funds the Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, with a Web site where additional information and technical assistance on PBIS can be obtained free of charge.

The continuation of this “PBIS advocacy” was documented up to the present time in Part I of this Blog. In addition, the reasons why this advocacy is inappropriate (politically) and unfounded (from a science-to-practice perspective) also were discussed.

In the end, we concluded Part I warning:

Districts and schools to be cautious—if not wary—about the U.S. Department of Education’s (and, perhaps, their State Department of Education’s) advocacy of the PBIS (Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports) Framework as a viable one to help them decrease seclusions and restraints with the most behaviorally-challenging students.

In this Part II of the series, we will discuss:

- My involvement, as an Expert Witness, in a number of federal court cases involving excessive numbers of seclusions and/or restraints of student with disabilities— especially those who demonstrate the most challenging behaviors. Here, we will discuss the common characteristics of these cases from a legal and student perspective.

- What state departments of education are providing (and not providing) relative to training professionals in their states in the interventions that will decrease or eliminate the need for student seclusions and restraints, and where the PBIS framework fits in

- What analyses and specific interventions state departments of education need to provide to close the PBIS framework’s gaps so that school personnel can be more successful with behaviorally challenging students

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

When Departments of Education Use PBIS to Decrease School Seclusions and Restraints

One of my many professional “hats” involves my work as an Expert Witness across the county in federal and state court, and due process hearings. Over the years, I have testified innumerable times in court cases related to the educational and special education rights of students; corporal punishment and effective interventions for students with social, emotional, and behavioral challenges; and school seclusions and restraints. While I often work to advocate for students and their parents, I have accepted cases where I am defending districts and even state departments of education.

Critically, I only take cases that I believe in. . . cases where I hopefully can make both a personal impact (for my clients), and a systemic impact at a broader level.

Over the years, I have been an Expert Witness on a number of cases—in vastly different states—where students with disabilities have been secluded, restrained, and corporally punished. Many of these cases involved students with significantly complex disabilities and/or with significant behavioral challenges that the schools were not addressing through intervention.

Many of these cases also have direct implications to the training being provided by state departments of education (SDoEs) across the country. As I have noted in the past, what SDoEs do in areas related to students with behavioral challenges is always interesting to me as I worked for the Arkansas Department of Education for 13 years helping to oversee the training exactly in this area.

Given my past experiences, I have analyzed state-level seclusion and restraint data—over the past 30 years, but even more recently over the last five school years as these data have become more readily available, so that I can confidently make the recommendations in this Blog.

Specifically at issue are schools that are secluding and/or restraining students with disabilities at an excessive level (sometime, many times per week). Some of these students are being put in isolation rooms. And many of these students are not receiving the strategic and/or intensive interventions to address the root causes of the students’ challenging behaviors, thereby resulting in the need to reactively seclude or restraint these students.

Critically, if a school were to think (inappropriately) that a seclusion or restraint is a strategic intervention—in and of itself, then the intervention goal should be to change the student’s behavior such that no future seclusions or restraints are needed.

At this point, one would have to ask,

“How many seclusions or restraints provide enough data to tell the school that this ‘intervention’ is not working and should be stopped— triggering the need for new analyses and (hopefully) different and more successful interventions.”

_ _ _ _ _

From a legal perspective, virtually all of the federal court cases that I have assisted with in this area have involved violations of:

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004)

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973

- Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

- The Elementary and Secondary Education (ESEA/ESSA, 2015)

While many are familiar with IDEA and ESEA/ESSA, let me provide a brief overview of the other two federal laws and the elements that are most often cited in seclusion and restraint cases.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 protects the rights of individuals with disabilities in programs and activities that receive federal financial assistance, including federal funds. More specifically, this regulation requires a school district to provide a “free appropriate public education” (FAPE) to each qualified person with a disability who is in the school district’s jurisdiction, regardless of the nature or severity of the person’s disability.

Section 504 states:

[N]o otherwise qualified individual with a disability . . . shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance" [29 U.S.C. § 794(a)]. Moreover, the Rehabilitation Act regulations hold that educational programs that receive federal funds "shall provide a free and appropriate public education to each qualified handicapped person who is in the recipient's jurisdiction, regardless of the nature or severity of the person's handicap" [34 C.F.R. § 104.33(a)], and that public entities are required to make reasonable modifications in policies, practices, or procedures when they are needed to avoid discrimination on the basis of a disability [28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(7)].

_ _ _ _ _

Title II of the American with Disabilities Act

Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) states that "no qualified individual with a disability shall, by reason of such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities of a public entity or be subject to discrimination by any entity" [42 U.S.C. § 12131/§ 12132; 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(a)].

The regulations implementing this law also require that a "public entity shall administer services, programs, and activities in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs of qualified individuals with a disability" [28 C.F.R. § 35.130(d)]; and that public entities must modify their practices, policies, and procedures as necessary to avoid discriminating against individuals with disabilities [28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(7)].

According to the ADA, a public entity discriminates on the basis of disability when it, among other actions:

- Denies a qualified individual with a disability the opportunity to participate in or benefit from a benefit or service;

- Affords a qualified individual with a disability an opportunity to participate in or benefit from a benefit or service that is not equal to that afforded others;

- Provides a qualified individual with a disability with a benefit or service that is not as effective in affording equal opportunity to obtain the same result, to gain the same benefit, or to reach the same level of achievement as that provided to others; or

- Otherwise limits a qualified individual with a disability in the enjoyment of any right, privilege, advantage, or opportunity enjoyed by others receiving the benefit or service

- Uses criteria or methods of administration that have the effect of discriminating against students with disabilities

_ _ _ _ _

My purpose in this Blog is not to re-defend past cases. Instead, I want to make three points that are based on publicly available data—drawn largely from the state department of education level.

- SDoEs are not fully analyzing their state’s seclusion and restraint data such that they understand the functional nature of the problem, and how and why the numbers are changing over time.

- SDoEs often focus predominantly on the incident numbers. They typically do not collect data that would help functionally identify the root causes of the student behaviors that are prompting the need for seclusions and restraints.

- Many SDoEs are doing a lot of PBIS framework-driven training. This training rarely (if at all) is aligned with the information and root cause analyses noted as needed in the two bullets above. Moreover, the training rarely (if at all) is coherent, comprehensive, or scientifically-based. The training misses many of the social, emotional, and behavioral interventions that, once again, can help prevent the need for crisis-oriented seclusions and restraints.

Ultimately, my recommendation to all states using the PBIS framework to guide the professional development that they hope will help their districts and schools to avoid the need for student seclusions and restraints is to:

Scrap the framework and rebuild the professional development with a truly defensible science-to-practice model. When SDoEs use the PBIS framework—from the National PBIS TA Center—they are using a framework (as previously document) that has no science-to-practice validity in this area.

The fact that I have been an Expert Witness in so many of these cases nationwide, in states where the SDoEs are using the PBIS framework, suggests (at the very least) that the framework has not successfully addressed the types of serious student behaviors that districts then are responding to with seclusions and restraints.

From my perspective, SDoEs who find themselves at this point should not engage in a “remodeling project” that “tinkers around the edges.” They need to level the entire system, and re-build it from the ground up.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Section I: Analyzing States’ Seclusion and Restraint Data

When I am an Expert in a federal court case focused on one or more student seclusions and restraints, I always look at the publicly available state data. As discussed in Part I of this Blog series, most states began to collect this data during the 2012-2013 school year. While this means that there are no (or virtually no) national data before 2012, we at least have five years of longitudinal data available from most states—although the 2015-2016 state data are not yet posted on the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) website (as of this writing) for analysis.

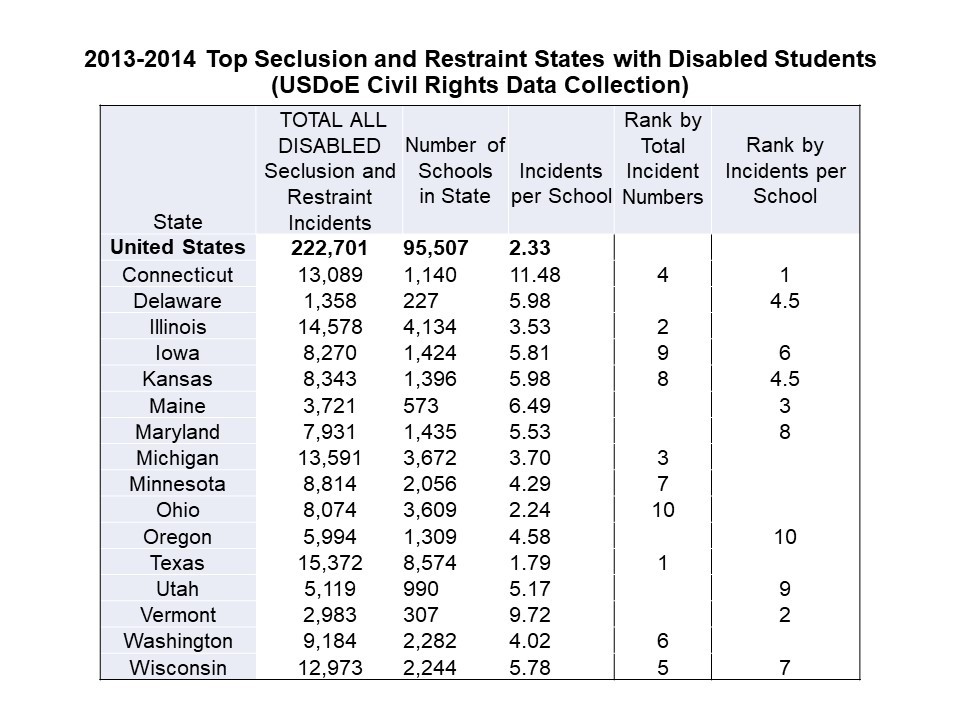

Nonetheless, in order to get a sense of different states' seclusion and restraint incident levels for students with disabilities, we analyzed the 2013-2014 school year data. To do this, we pooled seclusions and restraints for all students with disabilities—that is, those receiving services as students with disabilities under both IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. We then analyzed the data to identify (a) the “Top Ten” states that were secluding or restraining students with disabilities in sheer absolute numbers, and (b) the “Top Ten” states that were secluding or restraining students with disabilities per school in the state. While there are other ways to analyze these data, we thought that these would satisfactorily make our points.

Below is a table with the results of our analyses.

From a state-by-state perspective (once the 2015-2016 data are available), it will be interesting to see if the number of seclusions and restraints have increased or descreased during the five years that these data have been kept.

But for right now from a PBIS perspective, it is interesting to see Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, and Oregon on the list above. From my (and other national leaders') perspective(s), these are states with the some of the most well-established state PBIS networks in the country. The PBIS National TA Center has been jointly housed for many years at the University of Oregon and the University of Connecticut. And National PBIS leaders are often drawn from the state PBIS centers in Illinois, Maryland, and Michigan. While there certainly are state-specific issues always present, one would think that these well-established PBIS state programs would be so well-established in the schools in their respective states that these states would not be on the list above.

But another layer of analysis is needed.

_ _ _ _ _

Disaggregating the Data by Disability

In order to fully understand the data above, they need to be disaggregated across the thirteen disability areas identified in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004).

That is, for students being served by IDEA, seclusion and restraint data need to be disaggregated and analyzed by the following disability areas:

- Specific Learning Disability

- Speech or Language Impairment

- Multiple Disabilities

- Hearing Impairment

- Orthopedic/Physical Impairment

- Visual Impairment

- Deaf-Blindness

- Traumatic Brain Injury

_ _ _ _ _

- Other Health Impairment

- Intellectual Disability

- Developmental Delay

- Emotional Disturbance

- Autism

The reason for the line between the groups above is that, based on our analyses of multiple states, the students with disabilities in the lower group receive far more seclusions and restraints than the students in the upper group.

Clinically, this is not a surprising result in that the students in the lower group most often present with the most significantly challenging behaviors that those in the upper group. But even here, in most of the states in our analysis, students with Autism and Emotional Disturbances received significantly more seclusions and restraints than even the other three students with disability in the lower group.

At the same time, in our experience in most states, students identified with Developmental Delays: (a) are identified in preschool as part of IDEA’s child find and early intervention requirements; (b) have significant behavioral concerns; and (c) often are “re-labeled” as either Autistic, Emotionally Disturbed, or Other Health Impaired at some point in elementary school.

And, consistent with OSEP and IDEA, most (but not all) students with Other Health Impairments typically have attention deficit disorders, and many of these students often are unmedicated consistent with parent wishes. These students are often well-represented within the group of students receiving only Section 504 services or accommodations.

_ _ _ _ _

The implications? Regardless of our analyses, each individual state must analyze its own annual seclusion and restraint data by specific disability area. This needs to be correlated (see the two sections below) with the specific intervention training that is occurring statewide for students in the "high-hit" seclusion and restraint disability groups. Ultimately, in order to change the incident levels of seclusions and restraints with behaviorally challenging students, professional development—at the SDoE and district levels—most probably needs to focus on the social, emotional, and behavioral issues that are common to students with autism, emotional disturbances, developmental delays, and other health impairments (see, once again, Sections II and III below).

But the fact remains that many SDoEs are trying to address the seclusion and restraint dilemma using the National PBIS TA Center’s framework. And the data suggest that this is not working.

And so, the story continues.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Section II: Analyzing the Root Causes of the Behaviors Triggering Seclusions and Restraints

In a past life, I was the PBIS lead and primary contact in the Arkansas Department of Education for 13 years. Given this, I am fully aware of the intricacies within the National PBIS TA Center’s blueprint for Tier II, Tier III, and PBIS/School-based Mental Health intervention training.

And the intensive training needed to address the social, emotional, and behavioral root causes that result in schools needing to seclude and/or restrain students with autism, emotional disturbances, developmental delays, and other health impairments is wholly insufficient.

In short, most SDoEs do not have, and are not enacting, a systematic strategic plan to specifically and effectively address the assessment-to-intervention professional development needs of its districts and schools relative to their most behaviorally-challenging students.

Indeed, many SDoEs have never conducted an analysis of the students with autism, developmental delays, emotional disturbances, and other health impairments who are being frequently secluded or restrained to determine:

- The underlying reasons for their many behavioral challenges;

- The interventions needed by these students, and the interventions that are actually being delivered;

- What successful schools are doing, during significant behaviorally-challenging situations, to resolve these situations without the need for seclusions or restraints; and

- What schools are not doing, during similar challenging situations, that are resulting in seclusions or restraints.

Only with this information can a SDoE truly and strategically plan for the professional development and on-site technical assistance needs of their schools and students.

_ _ _ _ _

Root Cause Examples of Students’ Challenging Behavior

Relative to assessing the root causes of students’ challenging behavior, practitioners need to begin by understanding three principles:

- Principle 1. The assessment and intervention focus for all students is on their specific social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills.

Even though some students need interventions that decrease or eliminate inappropriate or maladaptive social-emotional behaviors, a comprehensive intervention program concurrently plans for prosocial, emotional control, and replacement behaviors.

- Principle 2. Given #1, assessments should not result simply in diagnostically labeling a student. If this occurs, anyways, interventions cannot be chosen based on these labels.

If a school was developing individual intervention plans for five autistic students, they would need to know (a) what specific social, emotional, and behavioral deficits the five students exhibit; (b) what replacement behaviors are warranted; (c) the root causes of the self-management gaps; and (d) which individual interventions, in the context of the root causes and from a science-to-practice perspective, will help the students close the gaps and attain the replacement behaviors.

These will differ for each of the students (regardless of the “common” label). . . hence, the reason for the individual root cause analyses and intervention plans.

- Principle 3. A formal Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) is not always appropriate as the “root” of the root cause analysis.

FBAs should be conducted only when they can validly answer the specific diagnostic questions that are present for a case. FBAs typically answer questions that relate to a student’s motivation in choosing to demonstrate an inappropriate behavior. If the student does not have the skills to demonstrate the desired, appropriate behavior, an FBA will not be accurate. And if the student’s behavior is biologically-based, the same is true.

I see far too many FBAs conducted with autistic students when some (sometimes, most) of their behavior is biologically-based. When behavior is biologically-based, there typically is no motivational function to the behavior. Thus, once again, any FBA “results” are often inaccurate, and there has been no productive “return” on the time invested in completing the FBA.

_ _ _ _ _

Beyond these Principles, some of the primary reasons why students demonstrate social, emotional, or behavioral problems in the classroom include:

- There are (known or undiagnosed) biological, physiological, biochemical, neurological, or other physically- or medically-related conditions or factors that are unknown, undiagnosed, untreated, or unaccounted for.

- They do not have positive relationships with teachers and/or peers in the school, and/or the school or classroom climate is so negative (or negative for them) that it is toxic.

- They are either academically frustrated (thus, they emotionally act out) or academically unsuccessful (thus, they are behaviorally motivated to escape further failure and frustration).

- Their teachers do not have effective classroom management skills, and/or the teachers at their grade or instructional levels do not have consistent classroom management approaches.

- They have not learned how to demonstrate and apply effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and/or emotional coping skills to specific (school-based or home-based) situations in their lives.

- They do not have the skills or motivation to work with peers—for example, in the cooperative or project-based learning groups that are more prevalent in today’s classrooms.

- Meaningful incentives (to motivate appropriate behavior) or consequences (to discourage future inappropriate behavior) are not (consistently) present.

- They are not held accountable for appropriate behavior by, for example, requiring them (a) to apologize for and correct the results of their inappropriate behavior; and (b) role play, practice, or demonstrate the appropriate behavior that they should have done originally.

- Their behavior is due to past inconsistency-- across people, settings, situations, or other circumstances. For example, when teachers’ classroom management is inconsistent, some students will manipulate different situations to see how much they can "get away with." Or, when peers reinforce inappropriate student behavior while the adults are reinforcing appropriate behavior, students will often behave inappropriately because they value their peers more than the adults in the school.

- They are experiencing extenuating, traumatic, or crisis-related circumstances outside of school, and they need emotional support (sometimes including mental health) to cope with these situations and be more successful at school.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, if we do not know and understand these root causes, we will never identify and implement the right interventions or solutions.

For students whose behavior escalates to the point that schools use seclusions and restraints, a big part of the root cause analysis should also focus on their emotional control and coping skills, and the situations that trigger the behavioral escalation. These assessments must be ecological in nature. They need to look not just at the student, but at how other people, task and situational demands, settings, and interactions are related to problem at-hand.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Section III: What Strategic or Intensive Interventions Can Replace the Need for Seclusions and Restraints

In my experience, SDoEs are doing a lot of PBIS training, but it often is occurring in the absence of the analyses discussed immediately above.

But, critically, most SDoEs’ PBIS training is missing the many strategic and intensive (“Tier II and Tier III” in the PBIS world) social, emotional, and behavioral interventions that, once again, could help prevent the need for crisis-oriented or reactive seclusions and restraints. In addition, it is missing the training in when and how to involve out-of-district community professionals who need to provide medical, clinical, and therapy-related supports to the most-challenging students.

More specifically, some of the interventions that SDoEs need to integrate into the professional development training programs in this area for their district colleagues include:

Emotional Control and Coping Interventions/Therapies

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation Therapy and Stress Management

- Emotional Self-Management (Self-awareness, Self-instruction, Self-monitoring, Self-evaluation, and Self-reinforcement) Training

- Emotional/Anger Control and Management Therapy

- Self-Talk and Attribution (Re)Training

- Thought Stopping approaches

- Systematic Desensitization

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

- Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)

- Structured Psychotherapy for Adolescents Responding to Chronic Stress (SPARCS)

- Trauma Systems Therapy (TST)

_ _ _ _ _

Motivational Interventions

- Positive Reinforcement, Schedules of Reinforcement, and Fading Techniques

- Differential Reinforcement of Alternative, Other, Low Rates, and Incompatible Behaviors

- Extinction/Planned Ignoring

- Response Cost/Bonus Response Cost

- Positive Practice and Restitutional Overcorrection

- Group Contingency (Independent, Dependent, Interdependent) Interventions

- Behavioral Contracting

- Educative Time-Out

- The Good Behavior Game

- Check-In/Check-Out

- Check and Connect

_ _ _ _ _

Skill Instruction Interventions

- Intensive Social Skills Training (Interpersonal, Social Problem-Solving, Conflict Prevention and Resolution, and Emotional Control and Coping skills)

- Cueing, Prompting, and Stimulus Control

- Attention-Control Training

_ _ _ _ _

At the same time, as noted above, many of these students need additional interventions that include medication, intensity community-based individual and family therapy, and specialized school settings—so that the right interventions can be implemented in the right ways.

This is why an ecological approach is necessary, and why the integration of school, family, and community services is essential.

_ _ _ _ _

Because of my ongoing work in the schools with high-needs students, I know that some students present with such significant, diverse, and historical needs that there are no silver bullets. However, in the absence of schools having the skills, resources, and capacity to select and implement many of the interventions above, we really do not know the levels of success that we might have with these students.

Let’s put the “horse before the cart.” Let’s get these interventions into the hands of the right school professionals, and let’s see what happens. We need to empower our colleagues with the tools to get the job done.

In the final analysis, I have never met anyone working in the schools who wants to seclude or restrain a student. This is not to excuse these incidents. . . it is to embark on a systematic plan to diminish them.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

In all of my years of interacting with OSEP, the National PBIS TA Center, state departments of education, and districts/schools using the PBIS framework, very few of the interventions identified in Section III have ever been systematically included (if at all) in their PBIS training programs, materials, or protocols. These omissions can now be added to the other significant issues that I have previously discussed relative to the PBIS framework (see the Blog citations in the Introduction of this message), and they reinforce the PBIS caution stated clearly in the first Blog in this two-part series.

Relative to any court case, there rarely are any real winners. Court cases involving students with disabilities do not occur unless (a) the students either are not receiving appropriate services, supports, and/or interventions; or (b) parents and school personnel are having serious disagreements and are at an impasse

Without being naïve, we need to design the multi-tiered systems that “work” even for students with the most significant social, emotional, and behavioral challenges. The national seclusion and restraint data are telling us that we are falling short.

And the same data are telling us that many SDoEs need to (re)look at their data, and (re)develop their plans to address the professional development, consultation, and technical assistance flaws in their current approaches to preventing and diminishing the need for seclusions and restraints—especially with students with disabilities.

Finally, I am hopeful that these re-conceptualizations will include a serious look at the poor science-to-practice track record of the PBIS framework, and a complete move away from this framework and its suggested practices.

_ _ _ _ _

As always, I appreciate your dedication in reading and thinking deeply about these messages. As always, I am trying not just to critique the current (and historical) state of our educational affairs across the country, but to suggest field-tested and proven “other ways” to help us get the student, staff, and school outcomes that we all want.

If any of you—with your school or district team—would like to talk with me by phone, Skype, Google Hangouts, etc. about any of these (or other school improvement, academics or student discipline, or multi-tiered services) issues or practices, all you need to do is contact me and get on my schedule. The first conference call is totally free.

Meanwhile, some of you are on Spring Break. . . and others have it coming up. I hope that you enjoy your time off. . . it is well-deserve.

Until the next Blog, be successful and well !!!

Best,