When Schools Struggle with Struggling Students: “We Didn’t Start the Fire”

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

The last two weeks have been a blur. Just over two weeks ago, I landed in Singapore to keynote at an International Conference with over 1,000 delegates from around the world.

Today, I am flying home after a consultation with a community high school district just south of Chicago that I have been working with for the past year. While we have been focusing on redesigning their multi-tiered system of supports, there have been many challenges. Among them:

- The District receives ninth grade students each year from up to ten different feeder districts that it has no instructional control over.

- Many of the students are from working class homes where they are living in poverty, where community violence is omni-present, and where mental health and social service supports are lacking.

- Many of the students enter the District without the academic prerequisites to succeed in ninth grade, and the District is identifying some students as students with disabilities (receiving either 504 Plans or IEPs) for the first time because their feeder districts are not identifying them through Child Find.

- One high school in the District is in almost a daily state of crisis—dealing especially with students who make threats on social media, and who then come to school—forcing the school to expend administrative and related service time (with staff counselors, social workers, school psychologists) on threat assessments, ranging from potential mass shootings to individual and copy-cat suicides.

The “good news” is that the District has leveraged federal, state, and other funds such that they have sufficient instructional, administrative, and related services (including counselors and social workers) personnel.

The “bad news” is that the multi-tiered system of supports in the District and its schools:

- Is not aligned, integrated, calibrated, or consistent;

- Is not grounded by a sound data-based problem-solving process;

- Is geared more to testing students so that deficiencies, disabilities, and clinical conditions can be “described and diagnosed”—rather than to the functional assessment of students so that the root causes of their challenges can be determined and linked to the evidence-based strategies and interventions that will improve their academic and/or behavioral performance; and

- Does not have staff with the expertise to implement the aforementioned strategies and interventions—even if they were accurately determined.

A critical point in all of this is that, in my 35+ years of working across this country, what I am describing above is typical of most Districts.

What may be atypical is that this District is devoting 15% of its annual IDEA funds (as allowed by law) to professional development and on-site consultation to help prevent general education students from needing more strategic or intensive services and supports at the “deeper” ends of its multi-tiered continuum. It is also braiding this money with strategically-placed Title I and Title IV dollars so that its schools can literally get “the biggest bang for the buck.”

Finally, this District is “going slow to go fast.” They did not ask me to come in to “fix” or “upgrade” their multi-tiered system of supports.

We spent this first year (a) building relationships and listening to staff, administrators, students, and parents; (b) identifying District strengths and resources, weaknesses and limitations, opportunities and alignments, and barriers and threats; and (c) creating the underlying systems and the infrastructure for improvement and change.

And I believe, as with other districts and schools that I have worked with in the past, that we are going to be successful. . . on behalf of the students, their families, and the community.

But our success is tempered by “high and realistic” expectations. We are not going to solve every problem, service every need, or save every student.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

We Didn’t Start the Fire, and We Don’t Have Enough Extinguishers

I grew up with Billy Joel. One of his most notable songs is, “We Didn’t Start the Fire.”

The song’s lyrics include more than 100 rapid-fire citations of historical events, notable people, and memorable occasions between 1949, when Billy Joel was born, and 1989, when he turned 40. Joel got the idea for the song when he was in a recording studio and met a friend of Sean Lennon who had just turned 21. The friend remarked, "It's a terrible time to be 21," and Joel replied, "Yeah, I remember when I was 21. I thought it was an awful time. We had Vietnam, and drug problems, and civil rights problems, and everything seemed to be awful."

The friend replied, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, but it's different for you. You were a kid in the fifties, and everybody knows that nothing happened in the fifties.” Joel responded, "Wait a minute, didn't you hear of the Korean War, or the Suez Canal Crisis?”

Joel later said those headlines formed the basic framework for the song.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Blog, I am going to use “We Didn’t Start the Fire” metaphorically.

First of all, as in the song, I am going to string together a number of research studies and policy papers to make some somewhat fatalistic educational (school, staff, and student) points. And while I am linking these studies and papers to make my points—just as in the historical events that Billy Joel lists—some of these links are not causal.

Second, as in the song, “good history” will be mixed in with “bad history.” While it is important to learn from (and not just remember) history, some unfortunate events nonetheless reoccur.

To this point: Schools do not have full control over all of the incoming or intervening student, family, community, or political events that impact them on a daily basis (and sometimes “set them on fire”). Thus, schools cannot be held fully accountable for every student “failure”—especially when they are sometimes “playing with a 45-card deck.”

Said a different way: Sometimes schools “didn’t start the fire”. . . nor do they have the capacity “to fully extinguish the fire.”

Third, if a school is “on fire,” the goal is to minimize the impact of the crisis and to, hopefully, prevent the next one from occurring.

But crisis prevention often requires the redistribution of existing resources and the allocation (sometimes, for a short time) of new resources. For some, this sounds unfair—because many still hold the belief that a district’s resources need to be equally distributed across its schools. For others, they are looking for any resources because the district is underfunded and/or under-resourced.

This is all about equity.

But, in the end, real equity occurs only when all of the schools in a district receive the same financial, personnel, and resource “core” needed for success, and the schools with more student challenges (e.g., more at-risk, underachieving, unresponsive, and unsuccessful students) receive the additional financial, personnel, and resource allocation plus that they need to be fully successful.

This is what I call Core-Plus District Funding.

This is the essence of how districts need to practice “equity,” so that all of their schools have a chance to be “excellent.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Outlining and Beginning to Travel this Blog’s Road Ahead

Here are the threads that I am going to tie together in this Blog:

- Teachers’ relationships with their students are one of the strongest predictors of student engagement and learning.

- But fostering student engagement and learning is difficult when there is an ever-present inequity in schools that serve high numbers of students who are living in poverty.

- Many of these schools also serve some of the most challenging students in our country, and these schools are sometimes in a constant state of crisis.

- Because of the inequity, these students often do not receive the comprehensive multi-tiered services that they need, and the schools often do not successfully emerge from their persistent states of crisis.

- This then circles back to make it difficult for teachers to build strong, positive relationships with all of their students, thus impacting even more students’ educational opportunities and learning outcomes, and creating another “layer” of student challenges.

These threads are discussed within the metaphorical stages of “starting a fire” . . . watching the fire grow to the point that it is out of control.

_ _ _ _ _

The Tinder and Kindling

- Teachers’ relationships with their students are one of the strongest predictors of student engagement and learning.

A March 13, 2019 Education Week article [CLICK HERE], “Why Teacher-Student Relationships Matter,” reviewed a number of research studies which demonstrate that these classroom relationships have a significant effect on:

both short- and long-term improvements on practically every measure schools care about—higher student academic engagement, attendance, grades, fewer disruptive behaviors and suspensions, and lower school dropout rates. These effects were strong even after controlling for differences in students’ individual, family, and school backgrounds.

Among numerous citations, the article referenced a forthcoming Bank Street College of Education longitudinal study investigating the impact of highly effective teachers on low-income students’ engagement and critical thinking—an outcome resulting from their ability to create classroom norms that established students’ feelings of safety and trust.

The article also discussed a Review of Educational Research analysis of 46 studies (13 of them collecting longitudinal data) that reinforced the student outcomes described in the quote above.

The bottom line is that relationships do matter. [Hattie summarizes its meta-meta-analytic effect on student achievement at a strong 0.52.] They involve teachers’ sensitivity to student gender, race, culture, socio-economic status, and academic skills and potential. . . and an understanding of how—for example—student trauma and student disability impact interpersonal relationships and academic engagement.

But it is difficult to develop positive, consistent, and sustained relationships when teachers:

- Are new to the field,

- Have not received adequate training in classroom management,

- Do not have adequate resources and support,

- Have too many challenging students with different skill levels and varied social-emotional needs to teach at once, and

- Do not have experienced mentors who are available for multiple years.

And high-poverty schools possess most of these characteristics.

This leads us to our next thread.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Layering the Firewood

- Fostering student engagement and learning is difficult when there is an ever-present inequity in schools that serve high numbers of students who are living in poverty.

There are multiple levels of financial inequity that directly impact schools—and, especially, those serving high numbers of students living in poverty. Some of these inequities originate at the state level relative to its funding formulas and how it distributes educational funds to all of its districts. Other inequities occur at the district level relative to funds generated from local property taxes.

For high-poverty schools, these inequities result in fewer resources than middle class or suburban schools, and they indirectly relate to staff recruitment, experience, and retention. More specifically, schools with high number of students living in poverty typically are often (a) underfunded (especially relative to their students’ needs), and (b) staffed by less experienced teachers who, naturally, have more skill gaps, and who resign from the school more often and after fewer years in-rank.

Validating Inequities at the State Level. The Albert Shanker Institute recently released a report The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems (April, 2019) based on data from the 2015-2106 school year.

[CLICK HERE for the Report]

Using research, state and local spending patterns, and student test scores, the authors concluded that—while states are spending enough money for middle class and wealthier students to meet states' academic standards, they're spending less on students living in poverty. Critically, the Report notes that these students require more funding, because they require more-qualified teachers, stable learning environments, and wrap-around multi-tiered services.

According to the authors,

There is now widespread agreement, backed by research, that we cannot improve education outcomes without providing schools—particularly schools serving disadvantaged student populations—with the resources necessary for doing so. Put simply: we can't decide how best to spend money for schools unless schools have enough money to spend.

The vast majority of states spend well under the levels that would be necessary for their higher-poverty districts to achieve national average test scores. States should consider replacing their existing funding formulas with ones that provide more money for schools serving a high concentration of these students.

States historically have attempted to even out funding disparities between districts by providing more money to those with low property value and, inevitably, poorer students. But states are falling short in those efforts. While states currently spend on average around $13,000 on high-poverty school districts, states, they should be spending more than $20,000 on those districts.

_ _ _ _ _

Validating Inequities at the State and Local Levels. The Shanker Institute report followed a February, 2019 report from EdBuild, a non-profit organization that analyzes school funding issues.

[CLICK HERE for Report]

This Report notes the significant funding gaps that approximately 12.8 million of our nation’s students experience because they are enrolled in “racially concentrated” districts with student bodies where 75% of the students are non-white.

More specifically, the Report states that racially concentrated non-white districts receive, on average, only $11,682 of funding per student each year, while racially concentrated white districts receive $13,908 per student each year. As 27% of our nation’s students live in racially concentrated non-white districts, and 26% of our nation’s students live in racially concentrated white districts, this translates to a $23 billion funding gap per year that favors white over non-white districts. . . despite them serving approximately the same number of students.

NOTE that there is an additive year-to-year effect as this gap accumulates from year-to-year !!!

This racial divide becomes even more concerning when the high-poverty rates of these districts is considered. Here, it is critical to note that 20% of our nation’s students are enrolled in high-poverty non-white districts, but only 5% of our nation’s students live in high-poverty white districts.

Given this distinction, the funding gap noted above takes on an additional context. Specifically, high-poverty white school districts receive about $150 less per student than the national average. But these district still receive nearly $1,500 more than high-poverty non-white school districts.

This last comparison is further compounded in some states where property taxes, locally-raised sales taxes, and parent-initiated school fund-raisers (and donations) tend to disproportionately favor middle and upper-class schools over high-poverty schools.

At a functional, state-by-state level, the EdBuild Report states that, “7 million students are enrolled in high-poverty non-white districts in states that provide less funding, on average, to those systems than their high-poverty white counterparts. That is 78% of the students in racially concentrated, high-poverty districts across the states in our analysis.”

Once again, these funding inequities affect the resources and staffing of the concentrated non-white districts—and even more so, the concentrated non-white high-poverty districts.

The direct implications of these funding gaps are discussed next.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Sparks and Combustion

- Many of these (non-white high poverty) schools also serve some of the most challenging students in our country, and these schools are sometimes in a constant state of crisis.

The correlation between health, mental health, academic, and social, emotional, and behavioral challenges and students living in poverty has long been established. Recently, this correlational effect has included the triangulation of poverty, stress, and trauma—including the impact of hunger and poor nutrition, parental incarceration and loss, abuse and neglect, and the exposure to violence and drugs.

[See the Following Citations:

Poverty and Educational Failure

These factors then circle back to negatively affect students’ school attendance and expectations, classroom engagement and motivation, academic readiness and proficiency, emotional self-control and prosocial interactions and, ultimately, high school graduation and readiness for the workforce.

At the extreme, many high-poverty schools are constantly dealing with high numbers of (a) truant and chronically-absent students; (b) students with significant, multi-year academic skill gaps; and (c) students who are physical or school safety threats, or who have mental health needs that transcend the school’s available services. These students then impact the staff’s effectiveness and efficiency, the school’s climate and culture, and the educational process and its outcomes.

These correlations are clearly seen when analyzing where schools are rated on their respective state department of education report card each year. In general, the data consistently show that high-poverty schools tend to be the lowest rated schools in most individual states—a status that many superintendents consider “a crisis.”

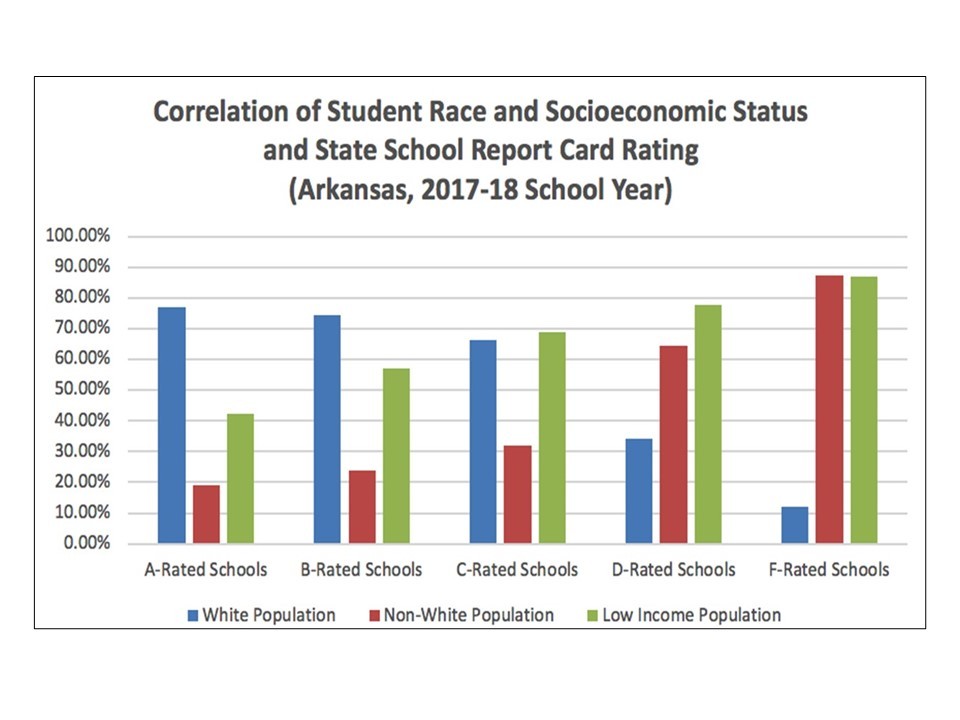

Let’s take my own state of Arkansas as an example.

Arkansas annually rates its schools—from “A” to “F”—on a composite of outcome indicators that include students’ academic proficiency and learning growth (including for English Second-Language students); high school AP course enrollment, ACT scoring and graduation; and student attendance and community service learning credits earned.

According to the 2017-2018 academic school year data, recently published in October, 2018 by the Arkansas Department of Education, 152 schools in the state received a school rating of A, 313 schools received a B, 380 schools received a C, 145 schools received a D, and 44 schools received an F.

Relative to race and school poverty, there were no A-rated and only three B-rated Arkansas schools that enrolled over 50% black or low-income students. Moreover, the student populations in the A-rated schools averaged 19% minority and 77% white students. Conversely, the student populations in the F-rated schools averaged 87% minority and 12% white students.

More specifically, across the A through F schools, the race by poverty breakdown was as follows:

Clearly, race and poverty appear to be strongly correlated to a school’s Arkansas state educational status. But, as suggested above, in between the race and poverty is the funding inequity, what the funds “purchase” relative to resources and staff expertise and longevity, and the fact that these high-poverty non-white schools have students with higher educational needs and lower academic proficiencies.

_ _ _ _ _

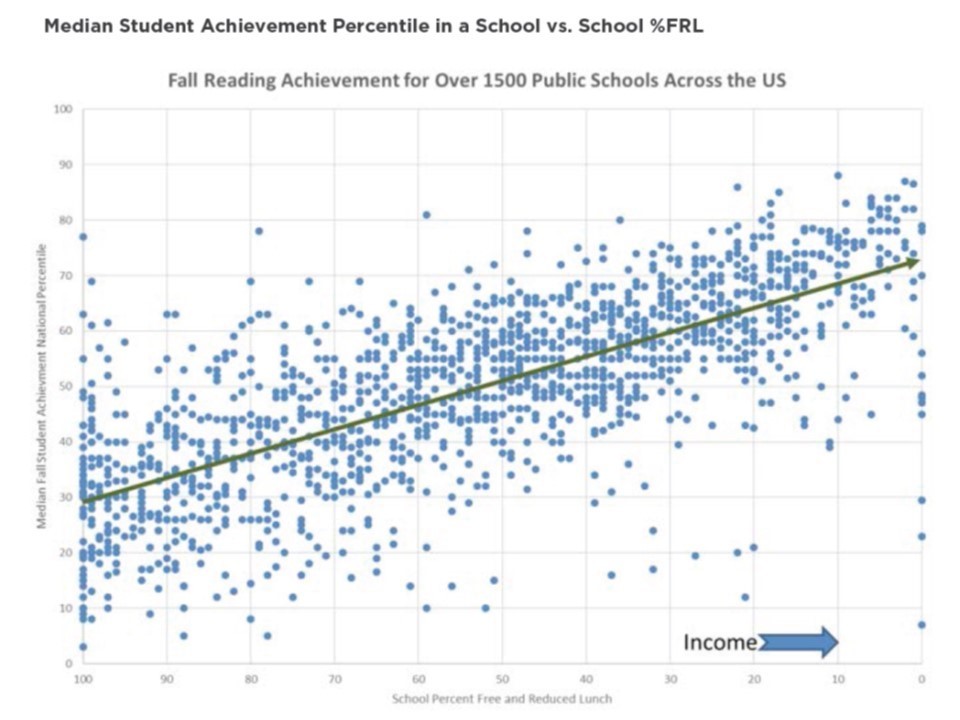

On a more national level, an October 2018 research report, Evaluating the Relationships between Poverty and School Performance, was published by the non-profit NWEA (which is best known for its interim assessment tool, the “Measures of Academic Progress”—MAP).

[CLICK HERE for the Report]

This report describes a study that analyzed the relationship between student achievement and growth and school-level poverty in about 1,500 U.S. schools randomly selected from over 9,500 schools that used NWEA’s MAP Growth assessment tool. This was done by correlating Fall 2015 and Spring 2016 MAP Growth data in reading with the percentage of students receiving a Free Lunch across the participating schools.

The results revealed a strong negative relationship between each school’s median MAP student reading scores and its school poverty status (see the Figure below). That is, students’ MAP reading scores were lower when the school had higher levels of student poverty. This was a strong effect as about 50% of a school’s reading achievement was accounted for by the percentage of students eligible for a Free Lunch.

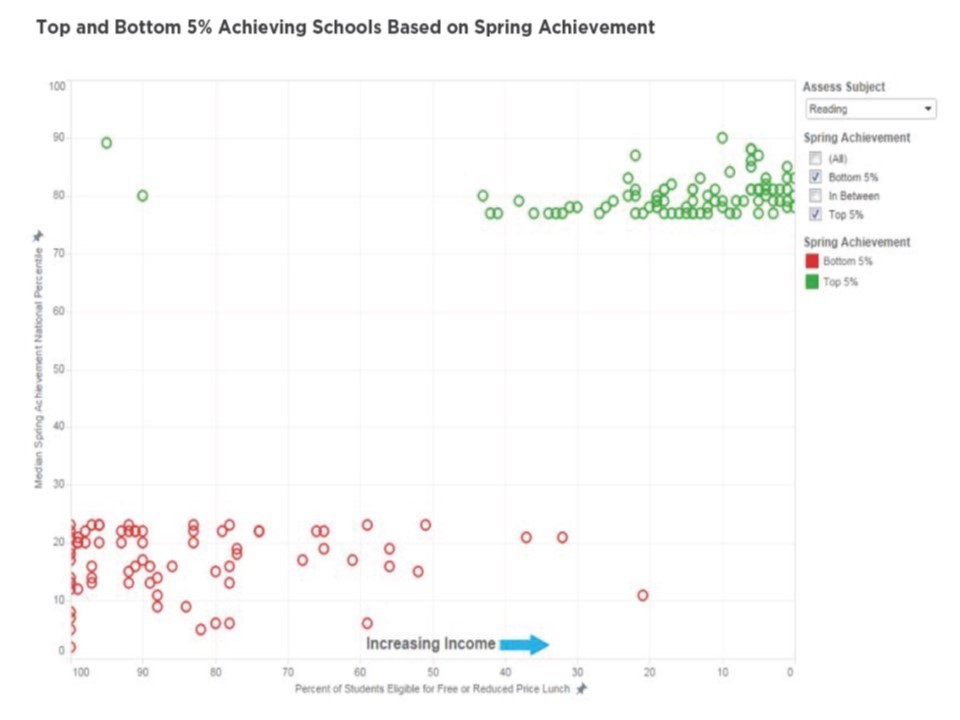

This strong negative relationship between poverty and achievement was similarly evident when the schools with the highest versus lowest Spring 2016 MAP Growth reading scores were compared. When analyzing the top and bottom 5% of these schools, the data showed that the top 5% MAP-scoring schools enrolled a significantly wealthier population of students, while the bottom 5% MAP-scoring schools enrolled significantly more Free Lunch (i.e., living in poverty) students (see the Figure below).

Once again, all of the information presented here supports the conclusion that high-poverty schools have some of the most academically-challenging students in our country. If these schools had the financial resources—the primary point of this Blog—they could more effectively address these students’ challenges. But the financial inequities already discussed often allow initial academic gaps and problems to progressively magnify as students move from grade-to-grade. . . to the point where long-term solutions are replaced by short-term survival.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Fire Becomes an Inferno

- Because of the inequity, students with academic and/or social, emotional, or behavioral challenges often do not receive the comprehensive multi-tiered services that they need, and the schools often do not successfully emerge from their persistent states of crisis.

Critically, most of the national discussions (see two studies below) regarding the impact of inequitable funding have focused on how high-poverty schools do not have important “foundational” educational programs, classes, services, and supports. While noting these gaps is important, many national policy reports miss the fact that the solutions needed to “right the equitable funding wrongs” must include both:

- The implementation of the missing foundational programs; and

- The availability of strategic and intensive interventions for students with significant academic and social, emotional, or behavioral problems—some that are student-specific, and some that are due to the programmatic gaps caused by the inequity.

These points are represented in a report, Unequal Opportunities: Fewer Resources, Worse Outcomes for Students in Schools with Concentrated Poverty, published by The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis in Richmond, VA in October, 2017. This Report analyzed the impact of poverty on the resources and classes available at over 1,800 public schools across Virginia.

[CLICK HERE for Report]

According to the Report, “The findings are clear. Students who have fewer resources outside of the school building are getting shortchanged in the classroom as well. And the differences are striking.”

The Report went on:

Students in high poverty schools have less experienced instructors, less access to high level science, math, and advanced placement courses, and lower levels of state and local spending on instructors and instructional materials. The average teacher salary in high poverty schools was about $46,000 in the 2013-2014 school year compared to over $57,000 in low poverty schools. The students are the ones who feel the impact of these disparities, and the consequences are worse outcomes when it comes to attendance, school performance, and graduation rates. Only about one third of high poverty schools were fully accredited by the state.

This is tragic because it’s precisely in these schools that heightened funding can have the biggest impact, and it is high poverty communities that could benefit most from having more skilled, better educated workers.

It’s largely Virginia’s Black and Hispanic students that are being deprived of the opportunity to pursue their goals and career ambitions. That’s because students of color are extremely over-represented in high poverty schools. About one out of every six students of color (15 percent) in Virginia attended a high-poverty school in the 2013-2014 school year, as did more than one out of every five (22 percent) Black students—compared to just 3 percent of White students.

Alarmingly, these challenges are not shrinking—they are becoming more widespread across the state. The number of schools with high concentrations of students from low-income families has doubled since the 2002-2003 school year, while enrollment in these schools has more than doubled.

Other state reports suggest that this Virginia report is representative, and that the educational program, classroom, service, and support gaps experienced there are similarly present in high-poverty schools across the country.

_ _ _ _ _

A 2018 report from Public Impact and the Oak Foundation, Closing Achievement Gaps in Diverse and Low-Poverty Schools: An Action Guide for District Leaders, outlined some additional school gaps that are related to funding inequities.

These include: unequal access to excellent teachers, teacher bias and low expectations, the disproportionate number of white teachers and the related potential for cultural insensitivity and/or bias, fewer referrals of students of color and/or poverty to gifted and talented programs, rigid tracking and less access to advanced secondary courses and other academic opportunities, higher levels of disproportionate office discipline referrals and suspensions, and the disproportionate presence of learning challenges with less access to quality remedial or intervention services.

[CLICK HERE for Report]

The Report went on to recommend how to address—from a policy perspective—the funding gaps. Here, the Report encouraged district leaders to use a package of research-based strategies centered on three complementary goals:

- Outstanding learning for all

Guaranteeing excellent teachers and principals, including redesigning schools to enable the district’s excellent teachers and principals to reach all students, not just a fraction.

Ensuring access to high-standards materials and learning opportunities.

Using teaching methods and school practices that work, including screening for and addressing learning differences, personalizing instruction, and responding to trauma.

- Secure and healthy learners

Meeting basic needs, including meals and reducing school transitions from housing changes.

Fostering wellness and joy via school-based health clinics, social-emotional learning, and other building blocks of academic success, and addressing mental health challenges.

Supporting families by understanding and responding to individual and collective needs.

- Culture of equity

Addressing key equity challenges in schools, including teachers matching their racial and other identities, access to advanced opportunities, culturally relevant assignments, and research-based, non-discriminatory disciplinary policies.

Fostering community accountability via shared leadership that truly empowers.

Equipping individuals to act by developing leadership and addressing implicit bias via consistent, ongoing anti-bias training. If district leaders and their communities pursue these approaches, they can help equip low-income students and students of color to close gaps and succeed in large numbers.

While these recommendations are sound, they—as noted above—are largely focused on whole-system or whole-school reparations. They do not address the multi-tiered strategic and intensive academic and/or behavioral services, supports, strategies, and interventions needed by students who are products of the gaps (as above) caused by inequitable funding patterns.

But as the lack of an effective multi-tiered system results in a continuation or exacerbation of these student problems, the “fire continues to burn, and becomes an inferno.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

We Can't Stop the Fire

- This then circles back to make it difficult for teachers to build strong, positive relationships with all of their students, thus impacting even more students’ educational opportunities and learning outcomes, and creating another “layer” of student challenges.

To finish where we started, when teachers have students with academic or social, emotional, and/or behavioral challenges in their classrooms, and these challenges are not addressed, they potentially worsen and escalate into crisis mode. This, then, impacts the classroom on an ecological level, affecting its climate and other teacher-instruction interactions to the degree that other students’ progress is comprised. . . and then they potentially move into crisis.

Relative to high-poverty schools with inequitable funding: If the original student challenges were related to the funding gaps, and if there are limited or no funds for strategic or intensive interventions, then why would we expect the school to suddenly have resources or highly-skilled professionals to deal with the intensification of the crisis?

While there are no intervention “silver bullets” for some students’ needs, when a system is in crisis, the resources and interventions typically need to be focused on stabilizing the crisis before re-focusing on addressing the needs of (a) the individual students at the center of the crisis, and (b) the students who are at-risk of becoming the next phase or layer of the crisis.

But if there is no money to address the crisis, then the fire may have to burn itself out.

Metaphorically, this leaves you with rubble, and the need to fully re-build. In education, this is called “reconstitution”. . . or what happens to some schools when they “sell-out” and get taken over by a charter school or for-profit school company.

_ _ _ _ _

One Solution: Core-Plus Funding. While this is but one solution for the inequitable funding problem, and it clearly has political and fiscal implications, Core-Plus Funding is a potential and viable “equity toward excellence” solution.

Core-Plus Funding occurs when, for example, every district in a state or every school in a district receives, each year, the core funding that it needs to run a successful multi-tiered instruction and support program for all of its students. The “plus funding” are the additional dollars that are given to districts or schools to support the services, supports, programs, and interventions needed by at-risk, underachieving, unresponsive, unsuccessful, and failing students.

This “plus funding” is allocated (a) for the service needs of existing students; (b) to compensate for needs of students (e.g., from high-poverty schools) that have resulted because “plus funding” was absent in the past; and (c) to students who are at-risk, or are showing “early warning” signs, of future, potentially significant needs.

As suggested immediately above, to maximize its outcomes, Core-Plus Funding must occur from the federal to state to district to school levels. But a prerequisite to all of this, naturally, is adequate Core Funding that successfully supports the instructional, programmatic, resource, and related service needs for all of the students in every school.

Below, an equity-driven Core-Plus Funding continuum is suggested with “Core” and “Core-Plus” elements:

Core: Federal. Sufficient federal education funding which, when added to each state’s education funding, results in a level annual per pupil expenditure that is calculated to ensure all students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral progress and proficiency.

- Core: Federal. Federal special education funding allocated at the 40% above-per-pupil-expenditure level set in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

- Core: State. Sufficient state education funding which, when added to each district’s (where present) local education funding (and the federal funding above), results in a level annual per pupil expenditure that is calculated to ensure all students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral progress and proficiency.

- Core-Plus: State. Sufficient state special education funding—as well as a Core-Plus distribution policy (that guides the allocation of federal special education “pass-through” funds)—such that the differential needs of students with disabilities at the district/school levels are fully met.

This Core-Plus provision could include the use of a state-level Catastrophic Funds for students with exceptional medical and/or disability-related needs.

- Core-Plus: District. It is recommended that the federal government pass legislation requiring states and/or districts that accept federal education dollars to use Core-Plus funding formulae. In turn, it is recommended that states either pass legislation or state departments of education pass regulations that require districts receiving federal or state funds to use Core-Plus funding formulae.

If this is done, then districts will need to pool their federal, state, and local funds so that (a) all students receive an annual per pupil expenditure that is calculated to ensure their academic and social, emotional, and behavioral progress and proficiency, and (b) students from poverty, with disabilities, using English as a second language, and others needing multi-tiered programs or interventions receive said services and supports.

- Core-Plus: District. As in this Blog’s Introduction, districts are encouraged to duplicate the practices used by my community high school district just south of Chicago. Specifically, they should consider (a) allocating 15% of their annual IDEA funds (as allowed by law) to professional development and on-site consultation to help prevent all students from needing more strategic or intensive services and supports at the far end of their multi-tiered continua; and (b) braiding this money with strategically-placed Title I and Title IV dollars so that they can literally get “the biggest bang for the buck.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

High-poverty non-white schools in this country receive significantly less money per pupil each year than high-poverty white schools and middle or upper class dominated schools, respectfully. This involves approximately 12.8 million students—many of them attending schools in urban settings.

Because of the financial inequity, these high-poverty schools have fewer resources than middle or upper class-dominant schools, and they are typically staffed by less experienced teachers who, naturally, have more skill gaps, and who resign from the school more often and after fewer years in-rank. In addition, the students in these schools have less access to high level science, math, and advanced placement courses, and less access to needed multi-tiered academic and social, emotional, and behavioral services, supports, programs, and interventions.

Correlated with the poverty, many of these students exhibit health, mental health, academic, and social, emotional, and behavioral challenges, that also triangulate with stress and trauma—including the impact of hunger and poor nutrition, parental incarceration and loss, abuse and neglect, and the exposure to violence and drugs.

From a school perspective, all of this translates into lower numbers of academically-proficient students, and schools that are either in their state’s school improvement programs or that are rated at the low end of the state’s school report card scale.

From a student perspective, all of this translates into negative effects on students’ school attendance and expectations, classroom engagement and motivation, academic readiness and proficiency, emotional self-control and prosocial interactions and, ultimately, their high school graduation and readiness for the workforce.

The financial inequity occurs at the federal level relative to funding for students with disabilities. Some of the inequity also rests at the state level relative to its funding formulas and how it distributes educational funds to all of its districts. Other inequities occur at the district level relative to funds generated from local property taxes.

In the final analysis at the school level, a vicious cycle is created. Despite the fact that teachers’ relationships with their students are one of the strongest predictors of student engagement and learning, these relationships are hard to establish and maintain given the effects (noted above) that correlate with schools that are underfunded—especially relative to the intensity of the conditions in their communities and of the needs of their students.

Because of the underfunding, many of these schools do not have the effective multi-tiered system of supports that the students need. Thus, the students’ problems persist or expand, classrooms and schools go into crisis, staff become reactive instead of proactive, more students are sucked into the negative climate and culture, and the entire cycle begins anew.

Systemic changes are needed—at the federal, state, and district levels—relative to educational funding policy, principles, and practice. While a Core-Plus Funding process was suggested, it will take more than this.

It will take a collective vision, and a decision—especially by the educators, community leaders, and parents in the successful districts and schools across this country—to see and advocate for the unsuccessful districts and schools in their states as their own.

Part of this vision and decision requires seeing what is happening—not just in these schools, but to these schools, and why. Some of this requires an understanding of history, white privilege, and equity rights. Some of this requires an understanding of the circular factors described in this Blog.

As Billy Joel sings:

We didn't start the fire.

It was always burning, since the world's been turning.

We didn't start the fire.

No, we didn't light it.

But we tried to fight it.

_ _ _ _ _

It’s time to fight it. . . .

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that this discussion has been useful to you.

As always, I look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any of the areas discussed in this Blog, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students, staff, school(s), and district.

Best,