Reviewing Two Recent Studies of Math Deficient Students

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Two Blog messages ago (on September 28th), I began a two-part discussion on:

Closing Academic Gaps in Middle and High School: When Students Enroll without Mastering Elementary Prerequisites (Part I)

The MTSS Dilemma—Differentiate at the Grade Level or Remediate at the Student Skill Level?

[CLICK HERE to link to that Blog Message]

While I usually publish two-part messages back-to-back, my October interview with Education Talk Radio host Larry Jacobs on:

The Traps and Troubles with “Trauma-Informed” Schools: Most Approaches Are Not Scientifically-Based, Field-Tested, Validated, or Multi-Tiered

was too time-sensitive to delay even a few weeks.

[CLICK HERE for the actual 28-minute October 4th Education Talk Radio Interview—if you missed it]

[CLICK HERE for the related Full Blog Message on how to implement effective science-to-practice Trauma Sensitive schools]

. . . But now we’re back on track.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Blog (Part II), we will briefly:

- Revisit our Part I discussion of how secondary schools currently do and (recommended) should address students who enter with academic skills so low that they can’t conceivably succeed in grade-level coursework; and then

- Review and apply the results of two important and topic-relevant research studies, one published in 2018—but referenced in a the74 Million article about a month ago, and another published this Fall by New Classrooms that addresses the results and implications of district, state, and federal policies that suggest—or even require—teachers to focus on grade-level standards regardless of their difficulty or their students’ mastery of the prerequisite skills that predict successful learning and advancement.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Revisiting the Secondary-Level MTSS Dilemma: When Students “Rise-Up” without Mastering Elementary- or Readiness-Level Prerequisites

In Part I, we discussed a common middle and high school pedagogical problem that occurs when students transition in (or up), and they haven’t mastered the prerequisite academic skills to succeed at the next grade level.

[CLICK HERE to Link to Blog Discussion, Part I]

While this occurs most often in the areas of English, reading, and literacy, or mathematics, calculation, and numeracy, we sometimes forget the impact on students’ learning when they are also unprepared to effectively write or communicate verbally at their grade levels.

And then there are the “lateral effects” when students’ low literacy or mathematics skills negatively impact their learning and performance in science, the social sciences, or in other transdisciplinary areas.

Typically, when students’ prerequisite academic skills are so low that everyone knows that they have virtually no chance of passing the next middle or high school course, most schools use one of the following Options:

- Option 1. Schools schedule the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and teach them at their grade levels— hoping that effective differentiated instruction will close the existing achievement gaps at the same time that the students learn and master the new, course-related content and skills.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 2. Schools use Option 1—scheduling the “not-ready-for-prime-time” students into their existing course sequences, and then they offer/provide tutors or tutoring (usually before or after school) to supplement the instruction and “close” the gaps.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 3. Schools “double-block” the students—scheduling them into the existing course sequences while also giving them an additional academic period a day (or less) to remediate their skills gaps.

_ _ _ _ _

- Option 4. Schools “double-block” the students, but the students have the same teacher for both blocks. This allows the teacher to follow the grade-level course’s syllabus, but s/he can spend time remediating students’ prerequisite skills gaps and adapting the instruction so they are prepared for and can learn and master the grade-level course material.

_ _ _ _ _

The Part I discussion emphasized the importance of completing, for all students with significant academic skill gaps, a data-based problem-solving process—including diagnostic assessments to determine the depth, breadth, and root causes of the gaps—so that needed services, supports, instructional strategies, and interventions are accurately identified.

While we understand the time, effort, and good intentions of our school colleagues, we still noted that:

Unfortunately, many schools have some data, but it is descriptive and not diagnostic data. And then they use these data to inadvertently play “intervention roulette”—throwing “interventions” at problems without really knowing the root causes as to why they exist.

To demonstrate the benefits of the recommended diagnostic assessment, data-based problem-solving process, we also noted that:

In reality, based on their data-based student analyses, schools may be well-advised to have Options 1, 3, and 4 available in order to maximize the learning and mastery of different students with different learning histories and instructional needs.

For example, while Option 2—Tutoring can be effective for students with narrow skill gaps, these Options will not work for students with significant academic skill gaps.

[For Option 3, obviously, schools need to coordinate the curriculum, instruction, and interventions in order to attain the strongest student outcomes.]

_ _ _ _ _

The Part I discussion then differentiated between middle schools versus high schools that have students with critical academic skill gaps.

Here we noted that middle schools (if they choose to take it) have more flexibility to “individualize” their students, staff, and courses than high schools— especially when the latter are not allowed (usually, by their state education codes) to give course credit for “remedial” courses. This helps deliver the targeted interventions that students with significant skill gaps need.

Indeed, we recommended that middle schools, if they know the academic and behavioral status of their rising 6th graders in April or May (an implicit recommendation), they can align their students, staff, and courses to flexibly meet the needs of different clusters of students—from those entering with significant academic skill gaps, to those whose academic skills already exceed the 6th grade courses they might “repeat.”

We concluded that, if middle school students with significant academic skill gaps “pass” their courses, but do not master the “elementary” and “middle school” skills that they need, we have simply passed the “problem” on to the high school “to solve.”

_ _ _ _ _

At the high school level, we described a number of “stark realities” (please see the original post). These led up to an Option 5 that we said—under explicit conditions—should be allowed, if not encouraged, by every state department of education and the U.S. Department of Education.

Option 5 is for students who have no chance of passing their next middle or high school course even using Options 1, 3, or 4 above—because their prerequisite academic skills are so low. This appraisal is based on objective, multi-instrument, diagnostic skill gap analyses of each struggling student—conducted at the relevant secondary school level.

Option 5 involves scheduling students into a course (or a double-blocked course) in their academic area(s) of deficiency that targets its focus and instruction on the students’ functional, instructional skill level. That is, the course takes students from their lowest points of skill mastery (regardless of level), and moves them flexibly through each grade level’s scope and sequence as quickly as they can master and apply the material.

This should be an instructional—not a credit recovery or computer/software-dependent—course with a teacher qualified both in instruction and intervention.

Moreover, this is the students’ only course in the targeted academic area, and the course instructors are responsible for making the content and materials relevant to the grade level of the student, even as they are teaching specific academic skills at the students’ current functional skill levels.

Thus, students are not concurrently taking a grade-level course in the same academic area (as in Options 1 through 4 above). In addition, the teachers in these students’ science, social science, or other courses also know the students’ current functional skill levels—differentiating their instruction as needed, while providing additional supports, so that the students’ areas of academic weakness do not negatively impact their learning in these “lateral” courses.

_ _ _ _ _

Possible Student Candidates for Option 5. Part I of this Series discussed the possible (combination of) reasons why rising-secondary students transition from elementary to middle school—or middle school to high school— without the prerequisite academic skills to succeed at the next grade level.

For students with significant academic skill and mastery gaps at the secondary level, the most common root causes described were:

- There were significant instructional gaps during the student’s educational history such that the student did not have the opportunity to learn and master essential academic skills.

This includes, for example, students who were (a) home-schooled, (b) had new teachers who were unprepared to teach, (c) had long-term substitute or out-of-field teachers for lengthy periods of time, or (d) were in classrooms with too many different student skill groups for the teachers to effectively teach.

_ _ _ _ _

- There were significant curricular gaps during the student’s educational history such that the student did not have the opportunity to learn and master essential academic skills.

This includes, for example, (a) schools without the appropriate evidence-based curricula or curricular materials to support teachers’ goals of effectively differentiating instruction; (b) schools where teachers—at the same grade level—were teaching the same content but with different algorithms, rubrics, or skill scripts that were then not reinforced by the next year’s teachers—especially as they “inherited” a mix of students who were taught specific skills in vastly different ways; or (c) schools that adopted grade-level curricula that were not aligned with state academic standards, and that did not articulate with the curricular expectations at the next grade level.

_ _ _ _ _

- The schools, attended by the student during his/her educational history, had an absent, inadequate, or ineffective multi-tiered system of supports that did not address his or her academic needs.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student was taught, over a long or significant period of time, in a school or classroom where the relationships or climates were so negative (or negatively perceived by him/her) that they impacted his/her long-term academic engagement, motivation, attendance, and access or ability to learn.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student had known or has newly-diagnosed (due to the root cause analysis) biological, physiological, biochemical, neurological, or other physically- or medically-related conditions or factors that significantly impacted his or her learning and mastery, or the speed that s/he learns and masters new skills.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student had (and may still have) frequent or significant personal, familial, or other traumatic life events or crises that impacted his or her academic engagement, motivation, attendance, and access or ability to learn.

_ _ _ _ _

- The student’s skill gaps created such a level of frustration that the resulting social, emotional, or behavioral reactions by the student (along an “acting out” to “checking out” continuum) overshadowed the original and present academic concerns—resulting in the absence of (or the student’s avoidance of) needed services or supports.

_ _ _ _ _

We concluded that the vast majority of these root causes point to the fact that students who will most benefit from Option 5 are students who did not have the opportunity to originally learn and master the academic skills that are now embedded in their significant skill gap.

At the same time, we emphasized that many of these student will need additional social, emotional, or behavioral services and supports so that the academic interventions can be successful. . . and that their motivation and positive, active engagement in the Option 5 course(s) and classroom will be a key factor in determining success.

This is especially true at the high school level, when students are confronted with the reality of a four-plus year high school career (which—from an adolescent’s perspective—may look worse than dropping out, or going for a GED).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Connecting Root Cause Analyses with a Continuum of Academic Supports and Interventions. Finally, in Part I, we emphasized that:

Option 5 will only succeed if the best services, supports, strategies, and interventions are matched to the root causes that explain why secondary students have such significant academic skill gaps.

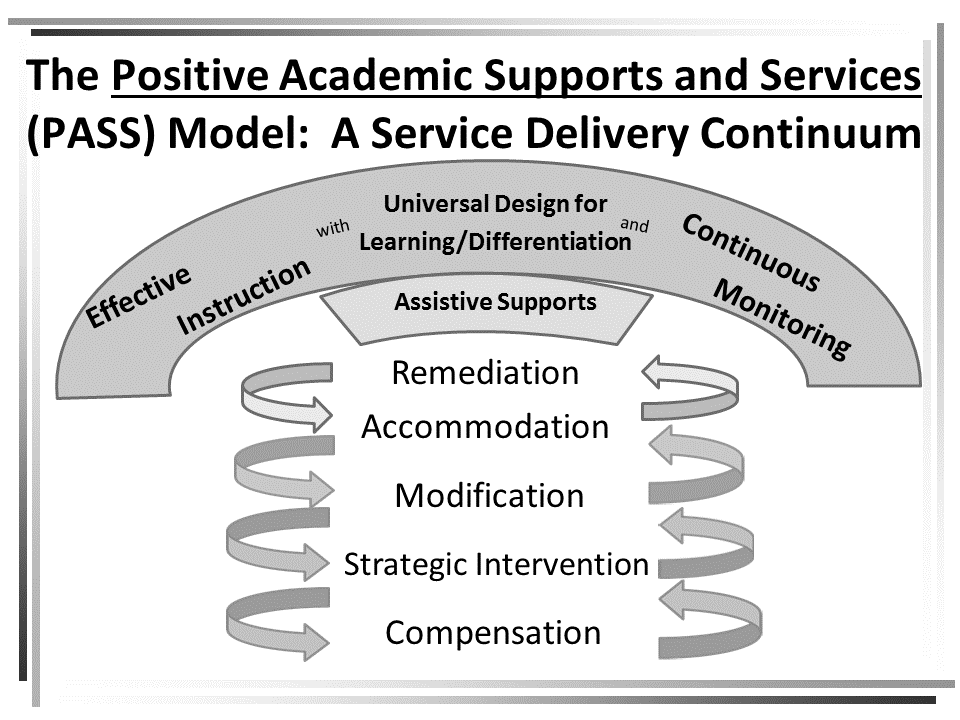

Expanding on this discussion, we described the key components of our Positive Academic Supports and Services (PASS) continuum. . . a science-to-practice blueprint that, in the context of the current discussion, is tailored to each individual student’s needs (see the Figure below).

[CLICK HERE to Link to Blog Discussion, Part I]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Validating the Magnitude of the Problem for Students with Significant Skill Gaps

To the continue the discussion begun in Part I, we are now going to focus on the impact and implications when students have significant skill gaps in mathematics at the secondary level.

Pedagogically, and in contrast to literacy, math tends to be more finite (i.e., there are right and wrong answers), more dependent on specific mathematical algorithms (e.g., formulae or clear problem-solving steps), and more sequentially scaffolded—with certain skills laying the “foundation” as prerequisite skills to a next set of skills. Thus, math is a perfect area to investigate the “impact and implications” noted above.

In a the74 article published on September 24, 2019, Joel Rose the CEO of New Classroom Innovation Partners, and Daniel Weisberg the CEO of TNTP—organizations that both focus on helping schools to address the needs of underachieving students—discussed their work with students with significant skill gaps in mathematics.

[CLICK HERE for the74 article, “Do Kids Fall Behind in Math Because There Isn’t Enough Grade-level Material, or Because There’s Too Much? It’s Both”]

Citing a 2018 TNTP Report, “The Opportunity Myth,” they stated that this Report found:

when students don’t meet grade-level standards, the problem usually isn’t that they tried and failed but that they were never given a real chance to try in the first place. The 4,000 students TNTP studied across five school systems spent hundreds of hours each year on work that was below their grade level. Those who started the year behind academically were the least likely to have grade-appropriate assignments—even when they were capable of succeeding on them—making it nearly impossible for them to ever catch up to their peers.

In essence, Rose and Weisberg are talking about (what we call) Instructional or Curricular Casualties.

These are students who “rise up” to middle or high school with significant skill gaps because of (a) the poor quality of previous mathematical instruction; (b) the poor quality of the progress monitoring, early intervention, or intensive intervention systems; (c) the poor selection or design of effective curricular lessons and materials in math; and/or (d) the poor sequencing or scaffolding of the math curriculum—including providing students opportunities for massed, distributed, and applied practice.

Critically, Instructional or Curricular Casualty Students can learn, they just have not had the sustained opportunity to learn.

_ _ _ _ _

This is in contrast to students who have legitimate difficulty learning and independently mastering their mathematical skills—even in the face of good, differentiated instruction, and well-designed and implemented curricular materials. While a small number of these students may have a specific learning disability in math, the vast majority need more strategic instruction a different instructional approach, smaller learning and mastery “chunks,” higher ratios of known to unknown material, and more positive practice repetitions relative to memorization and automatic recall or application.

_ _ _ _ _

Regardless of why a student has a significant skill gap in mathematics, the impact and implications are notable.

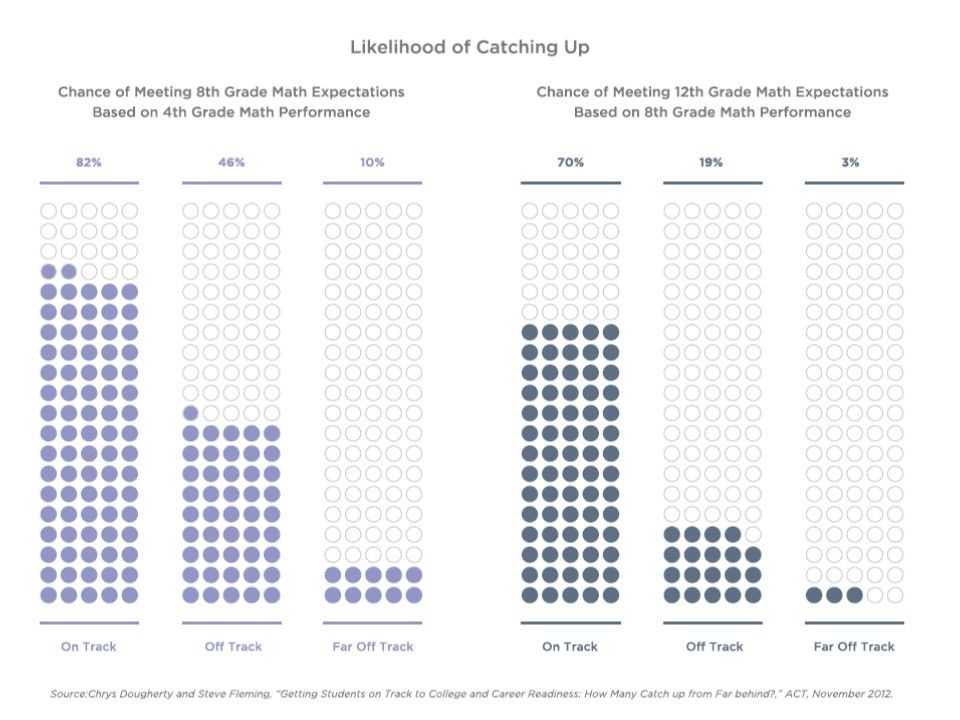

In their the74 article, Rose and Weisberg reproduced a figure (see below) from a 2012 ACT report that longitudinally analyzed tens of thousands of students who were behind in math in fourth versus eighth grade, respectively. The goal was to identify—from a normative perspective—how many students academically “caught up” over a four-year period of time.

As is evident in the figure:

- Students who began 4th grade “at grade level,” had an 82% probability of being on grade level in 8th grade—four years later.

- Students who began 8th grade “at grade level,” had an 70% probability of being on grade level in 12th grade—four years later.

- Students who began 4th grade “off track,” had an 46% probability of being on grade level in 8th grade—four years later.

- Students who began 8th grade “off track,” had an 19% probability of being on grade level in 12th grade—four years later.

- Students who began 4th grade “far off track,” had an 10% probability of being on grade level in 8th grade—four years later.

- Students who began 8th grade “far off track,” had an 3% probability of being on grade level in 12th grade—four years later.

From the Report, it appears that most of the (especially) “far off track” students were receiving Options 1 through Option 4 above. This Report and these data simply reinforce that these Options have a low probability of significantly improving the learning, mastery, and math proficiency of students with significant skill gaps—in both middle and high school.

This, at least, puts the consideration of Option 5 “on the table”—once again, in the context of both root cause analyses and multi-tiered systems of support.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The Iceberg Problem in Mathematics: How Policies, Practices, and Resources Point to Option 5

Rose and Weisberg’s the74 article goes on to reference a September 2019 Report released by Rose’s New Classroom Innovation Partners:

“The Iceberg Problem: How Assessment and Accountability Policies Cause Learning Gaps in Math to Persist Below the Surface . . . and What to Do About It”

[CLICK HERE for Report]

I encourage everyone to read this 75-page Report which provides compelling information on (a) how different math skills are scaffolded across most mathematics curricula; and (b) the cumulative (negative) effects that occur when students fall significantly behind in their learning and mastery of previous, now-prerequisite skills—and yet, they are scheduled into courses that teach at their current grade level.

Below, I briefly summarize the “Key Insights” from Report—conclusions that support the primary theses of this two-part Blog Series.

- Key Insight #1: Math is cumulative—unfinished learning from prior years makes it harder for students to master more advanced concepts.

Mathematical skills build upon one another over time.

Mathematical concepts and skills build upon one another as students advance through middle school. The instruction that students receive reflects a coherent body of knowledge made up of interconnected concepts and designed around coherent progressions from grade to grade so that students can build new understanding onto foundations built in previous years.

Through our work, we have continually leveraged academic research on how students effectively progress through the K–12 mathematics landscape in order to map specific mathematical concepts and skills to the college- and career-ready grade-level standards. In doing so, we see that each grade’s set of skills require students to have knowledge of prerequisite skills from prior years.

_ _ _ _ _

- Key Insight #2: Current educational policies favoring grade-level instruction (i.e., teaching students at their current grade placements) are hindering many students’ longer-term success.

Education policies are oriented around annual grade-level expectations.

At the core of today’s federal and state educational policies for K–12 schools is a system oriented around annual expectations at each grade level and a set of standards, assessments, and accountabilities designed to drive instructional behavior toward meeting those annual expectations.

These policies aim to advance several important principles, including:

• Providing every student with access to rigorous grade-level instruction that will prepare them for the future;

• Closing achievement gaps and combating systemic bias against historically marginalized student groups by providing equitable learning opportunities and setting clear and common expectations for success;

• Holding adults in school systems accountable for ambitious, measurable learning outcomes rather than process-oriented inputs;

• Giving families annual information they need to understand their student’s progress, make educational decisions for their student, and advocate for change; and

• Giving policy makers and system leaders information they need on an annual basis to evaluate school success and address areas for improvement.

The grade-level standards that lie at the heart of these policies are anchored in college and career readiness. ESSA requires states to adopt “challenging state academic standards” that apply equally to all public school students in the state in math, English language arts, science, and any other subjects the state designates. States (are supposed to) demonstrate the rigor of their standards by aligning (them) with entrance requirements for credit-bearing postsecondary coursework.

But in math, when students miss key steps along the way in this progression or learn at a pace that is faster or slower than the state standards anticipate, the standards alone do not provide guidance to teachers on where to focus instruction. They signal to a seventh grade teacher, for example, that all seventh-grade students should be taught seventh grade content—whether they happen to be performing two years behind grade level or two years ahead.

The grade-level expectations embedded in policy reflect a single path to college and career readiness for all students. They leave little room for other instructional paths to that same goal that are more attuned to each student’s incoming performance level.

_ _ _ _ _

- Key Insight #3: Balancing pre-grade level, on-grade level, and post-grade level skills to each student’s needs can better support their long-term success.

Evidence is emerging on the relationship between student performance and the level of instructional content.

While ESSA requires an accountability system that focuses on grade-level mastery, districts and schools are free to develop and apply their own parallel accountability systems so long as they continue to meet state and federal requirements.

Most districts generally measure growth in the ways reflected in their state’s ESSA plan. But some focus on different growth measures based on (other assessments that) include items from across multiple grade spans. These schools still take the state test and, for purposes of state accountability, their growth is measured in ways aligned with federal policy. But under their own district- or school-based accountability system, they are able to focus on comprehensive learning growth.

Over the last six years, our program has operated in districts and schools with different philosophies around teaching students grade-level material. In schools where accountability systems imposed at the district or school level are based on growth measures that cross multiple grades, we can tailor a personalized curriculum for each student that includes a mix of pre-grade, on-grade, and post-grade material, depending on their unique starting points.

For many students who enter sixth grade multiple years behind, this means spending meaningful time addressing unfinished learning in service of grade-level material. This can also mean not necessarily exposing students to all grade level standards in a single year, given the time it takes to fill multiple years of unfinished learning.

There is little evidence to suggest that for students who are far below grade level, focusing instruction exclusively on grade-level content is ineffective.

While evidence of the value of balancing pre- and on-grade skills is still emerging, it should be viewed against the evidence base for what policy currently incentivizes—providing all students with grade-level content.

Many studies have found that too many students in the past were subjected to repetitive, ineffective instruction that did little to prepare them for college and a career. Schools where low expectations and ineffective instruction reigned disproportionately were those that served low-income students, students of color, and other historically disadvantaged students. Students spent years in remedial math courses that got them no closer to graduating.

This unacceptable state of affairs has yielded policy and curricular remedies that focus on grade-level instruction and assessment as key drivers for ensuring instructional rigor. At the same time, we find little evidence in the research to support the notion that in middle grade math, grade-level content for students who have already fallen far behind works without careful without strategies to build up key missing skills.

One way researchers have explored the effects of giving students content far outside their current skills is by looking at students taking algebra in eighth grade instead of high school.

A policy push in the early 2000s placed many eighth-grade students in algebra who would have otherwise taken a pre-algebra eighth-grade math course. One study found that students enrolled in advanced eighth grade algebra with low incoming math skills performed about seven grade levels below their peers on NAEP and struggled with questions testing elementary-level understanding.

Another study found that low-achieving students pushed into algebra did less well in subsequent math courses through high school, especially in geometry. This is possibly because students never had a chance to build up prerequisite skills that would have helped them later on.

The above gives us reason to believe that in math, low-performing students pushed into grade level content without appropriate support and attention to prerequisite skills may not be better off in the long run.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This Blog Series has focused on the instructional dilemma that occurs when students transition from elementary to middle school—or middle school to high school—and their academic skill levels are so low that (a) they have no hope of learning or succeeding in the courses at the next grade level, and (b) their skill gaps are so significant that the different remedial options that most schools use will not close the gaps.

During the discussion, the four Options that most middle or high schools use to address this dilemma were described—noting their differential strengths and weaknesses, and how schools miss (or ignore) the fact that these options will not address these students’ significant needs.

We then detailed a number “stark realities” that we summarized in the following ways:

- If middle school students with significant academic skill gaps “pass” their courses, but do not master the “elementary” and “middle school” skills that they need, we have simply passed the “problem” on to the high school “to solve.”

- Moreover, if these students “pass” courses and “graduate” from their high schools without mastering the academic and related skills needed to truly succeed at the “college and/or career level,” the schools have not accomplished their educational mission and a disservice has been done to the students.

From a multi-tiered perspective, then, the goal is to complete (a) a data-based problem-solving process that links the results of a root cause analysis to strategic or intensive services, supports, strategies, and interventions; and (b) to consider a fifth option where students are taught at their functional skill and mastery levels, and where they receive the interventions and supports needed to learn, master, and progress through the academic skills needed to ultimately be successful at their true grade levels.

_ _ _ _ _

This current Part II presented information and data specifically in the area of mathematics. It was noted that, in contrast with literacy, math tends to be more finite (i.e., there are right and wrong answers), more dependent on specific mathematical algorithms (e.g., formulae or clear problem-solving steps), and more sequentially scaffolded—with certain skills laying the “foundation” as prerequisite skills to a next set of skills.

In addition, large-scale longitudinal data were presented demonstrating that students in fourth and eighth grade, respectively, who are “off track” and “far off track” relative to their grade-level mastery and proficiency in math, maintained their low academic standings four years later.

Additional information was presented demonstrating that the first four “catch-up” Options discussed in this Blog Series are questionable at best relative assisting students who are significantly behind in math in both middle and high school.

_ _ _ _ _

All of this suggests that middle and high schools need to seriously consider Option 5 for significantly skill deficient students. This Option involves scheduling students into courses (or a double-blocked course) in their academic area(s) of deficiency that target focus instruction at students’ functional, instructional skill levels (and not at their current grade placement). These courses should take students from their lowest points of skill mastery (regardless of level), and move them flexibly through each grade level’s scope and sequence as quickly as they can master and apply the material.

These courses should be the students’ only course in the targeted academic area, and the course instructors are responsible for making the content and materials relevant to the grade level of the student, even as they are teaching specific academic skills at the students’ current functional skill levels.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

I hope that the research, information, and ideas in this Blog Series have been useful, and I appreciate your ongoing support in reading this Blog. As always, if you have comments or questions, please contact me at your convenience.

And please feel free to take advantage of my standing offer for a free, one-hour conference call consultation with you and your team at any time.

Best,