The Neurological Science Does Not Add Up—Another Fad & More Wasted Time in Pursuit of a Silver Bullet (Part II)

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Our last Blog message (January 11, 2020) was the first in this current two-part Series dedicated to helping districts, schools, educators, and mental health practitioners understand the research to-practice limitations of (a) trauma-informed programs; (b) trauma-“infused” programs built on the SEL-CASEL or PBIS frameworks; and (in this Blog message—Part II) (c) trauma-focused programs that include mindfulness and meditation programs or approaches.

Critically, readers need to understand the differences between trauma-informed programs and trauma-informed practices.

Part I of this series stated very clearly that (a) there are many students who have experienced trauma-specific events in their lives; (b) these students need to be identified through objective multi-instrument assessments; and (c) these students need specific services, supports, strategies, and interventions—that is, trauma-informed practices—that address the social, emotional, and behavioral effects of these traumas.

[CLICK HERE to link to Blog Message, Part I:

Trauma-Informed Schools: New Research Study Says “There’s No Research.” Schools “Hitch-Up” to Another Bandwagon that is Wasting Time and Delaying Recommended Scientifically-Proven Services (Part I)

But Part I also emphasized that some students exhibit emotional reactions (e.g., “fight, flight, or freeze”) due to emotional triggers that are not trauma-related. In fact, we provided a number of examples of these non-trauma-related emotional triggers.

We also emphasized that ALL students demonstrating high frequency or significantly intense emotional reactions in school need to have their emotional triggers identified through objective and valid multi-instrument assessments.

Next, Part I discussed our concerns with trauma-informed programs—“pre-packaged” programs with many different components and activities that are largely implemented intact and school-wide. We emphasized that virtually all of these programs have not been independently and objectively validated through sound research across multiple settings and circumstances.

Here, we expressed our concerns that some districts and schools are implementing these programs—potentially wasting time, money, and other resources; and potentially delaying appropriate services and supports to students in emotional need, while making their problems worse or more resistant to change.

Finally in Part I, we put our “money where our mouth is”. . . as we summarized a recent study that reviewed over 9,000 other studies, published over the past ten years, that examined trauma-informed school programs.

Using objective, research-sensitive criteria, this study determined that none of the studies they analyzed met their criteria for sound research.

Our conclusion: Our concerns that schools are implementing “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive” programs that have not been objectively validated, do not work, and are counter-productive was supported.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Part II, we will discuss the relationship and inappropriate use of mindfulness and mediation with students experiencing trauma. Here, we will describe (a) the non-existent methodologically-sound or validating research for school-based mindfulness programs; (b) how one popular commercial company—that provides unvalidated mindfulness training to individuals and schools—rationalizes its existence (while making multi-millions of dollars and wasting precious school time and resources); and (c) how the biological and neuropsychological underpinnings of trauma-related student emotionality is inconsistent with the primary goals and desired outcomes of most mindfulness programs, and these programs do not have the multi-tiered psychologically-grounded clinical interventions needed by students with significant social, emotional, and behavioral challenges.

The theme across both Parts of this Series is that:

Districts and schools need to know the Trauma-Informed Care, SEL, Mindfulness, and Meditation research-to-practice as all of these areas have significant flaws that should result in educators questioning their use in schools.

Recognizing that districts and schools do not always have the time or expertise to evaluate the current research-to-practice, we hope that this two-part Series (and my previous Blogs on these topics) will help them to choose effective, multi-tiered approaches to address the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of students impacted both by trauma and by other emotionally-triggering situations, circumstances, and/or conditions.

We also hope to encourage districts and schools that have already adopted and implemented trauma-informed or sensitive programs to objectively and comprehensively evaluate their research, practice, and student-centered outcomes— especially with students who have strategic or intensive clinical needs.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Re-Introduction: Mindfulness and Meditation

Over the past few months, I have been updating my Stop & Think Social Skills Program’s manual and materials. The Stop & Think Program is an evidence-based program as designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and it has been adopted in thousands of schools nationwide since 1990.

Noting that the most-essential outcome of any social skills curriculum or program is to help students—across the preschool through high school age span—develop independent and adaptive social, emotional, attributional, and behavioral self-management skills, I have enhanced the Manual’s research-to-practice discussions of emotional regulation, control, and coping.

Significantly, in preparing these enhanced discussions, I re-reviewed not just the relevant psychological research, but also the relevant neurological research.

But I have also been “forced” to re-review the “research” on mindfulness and meditation—because this bandwagon has maintained its popularity in the popular press, and more districts and schools (still) seem to be adopting these practices without regard for the research.

Indeed, the popular press—including a number of well-established national professional teaching organizations— continues to publish testimonials or “case studies” where they conclude that their mindfulness program-for-the-day has “significantly and causally” improved school climate, student behavior, and staff instruction.

[Of course, the research methodologies underlying these cases studies are completely without merit, and there is no way—given these methodologies—that any causal relationships could ever be established.]

And yet, some districts and schools have inappropriately used these testimonials or case studies as their rationale for adopting these programs or practices.

In doing this, these districts and schools have fallen prey to one or more of the “challenges” discussed in the Introduction of this Blog message.

_ _ _ _ _

Pulling all of this together, this Blog section will provide the following:

- A brief summary of and references to our past Blog discussions in this area.

- A brief summary of our updated research review in this area.

- A substantive discussion of how the neurological research supports the psychological research explaining students’ emotional control and coping, and their emotional self-regulation and self-management.

SPOILER ALERT !!! The last discussion will largely invalidate the “connection” between the student-focused needs of most schools, and why they adopt mindfulness programs.

In our experience (and based many popular press case studies), most schools adopt mindfulness programs to change the emotional volatility and reactivity of students who have experienced trauma or who are exhibiting significant social, emotional, or behavioral challenges.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summarizing Our Past Mindfulness Program Discussions, and Reviews of the Mindfulness Research

During the past few years, I have devoted at least five Blogs to the Mindfulness “movement.”

In my February 13, 2016 Blog, I critically reviewed four research articles on Mindfulness that were published in 2013.

[CLICK HERE] Reviewing Mindfulness and Other Mind-Related Programs: More Bandwagons that Need to be Derailed? Why are Schools Wasting their Time and Resources on Fads with Poor Research and Unrealistic Results?

At the end of the Blog, I stated,

“Without reviewing data from the original development of the Mindfulness curricula or interventions used, these studies suggest that—if anything—'the jury is still out.’

None of these results objectively proved that the Mindfulness approaches had any short- or long-term effect on student behavior.

And, none of these results come close to making a compelling argument for adopting any of these Mindfulness approaches in any other classroom, school, or district.

(Critically,) (O)ne of the potential problems with Mindfulness is that—even if it works—any improvements in self-control, self-awareness, or attention do not necessarily translate into student improvements in demonstrating social, behavioral, emotional coping and control skills.

And these are the outcomes that educators are interested in.

Thus, just because students are able to be more attentive and focused on the present, this does not mean that they have learned, mastered, and are able to apply the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, or emotional control and coping skills needed to deal with that present.

If we are going to invest the money, time, and training that these Mindfulness programs require, why are we not, instead, investing in the evidence-based social and emotional skills programs proven to actually produce behavioral change?”

_ _ _ _ _

At the beginning of November 2017, we published a three-part Blog Series focusing on the implicit goal of most Mindfulness programs or approaches:

To help students to be more aware and in control of their emotions, thoughts, and behavior.

During this Series, we analyzed the research and practice of Mindfulness, concluding that—from an objective, data-based perspective—the approach does not deliver on this stated goal.

In order to focus educators’ attention on the best, research-based processes that DO meet this goal, we discussed how cognitive-behavioral strategies and interventions have over 35 years of research supporting their social, emotional, and behavioral efficacy with children, adolescents, and adults.

We then mused:

What would happen—relative to the goals above—if schools invested the same time, training, and attention to cognitive-behavioral strategies, with their longstanding record of student success. . . instead of a passing fad that educators will recall in the future with a deep breath and a roll of their collective eyes?

[CLICK HERE for Part I of the Series]

November 4, 2017 New Article Again Debunks “Mindfulness” in Schools: Teaching Emotional and Behavioral Self-Management through Cognitive-Behavioral Science and The Stop & Think Social Skills Program. . . Don’t We Really Just Want Students to “Stop & Think”?

_ _ _ _ _

[CLICK HERE for Part II]

November 18, 2017 Teaching Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Management Skills to All Students: The Cognitive-Behavioral Science Underlying the Success of The Stop & Think Social Skills Program

_ _ _ _ _

[CLICK HERE for Part III]

December 2, 2017 Teaching Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Self-Management Skills to All Students: The Cognitive-Behavioral Science Underlying the Success of The Stop & Think Social Skills Program

_ _ _ _ _

In Part I of this 2017 Blog Series, we discussed the past and current research, efficacy, and realities of Mindfulness programs in schools across the country, and the $1.1 billion industry-fed “bandwagon” that many districts have “jumped on” over the past few years.

Overall, the updated research cited in Part I made the following points:

- Most of the Mindfulness program research has either not been methodologically sound, or it has not produced objective and demonstrable success.

- The few studies that have shown “good evidence” have focused on adults with clinically-significant mental health issues (anxiety, depression, and pain), not on school-aged students.

- Rather than use the few studies that have shown “good evidence” to rationalize the use of Mindfulness in schools (or worse, someone’s subjective, personal pronouncements), educators need to read the substantial body of research that should eliminate the use of Mindfulness programs in schools.

- Sound research has not definitively demonstrated that Mindfulness programs are successful at the preventative (e.g., Tier 1) level in schools. In fact, the Behavior Research and Therapy study cited in Part I indicates the opposite.

- There are a significant number of large school districts and other schools (covered by the popular press) that are wasting precious professional development and classroom time and money on this fad.

- Students who need evidence-based approaches to address their social, emotional, and behavioral needs—but are receiving Mindfulness training instead—are potentially being harmed because more effective services are being delayed.

- Students would be far better served if their districts and schools were providing multi-tiered social skills training and cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches—given their long histories of demonstrated efficacy in hundreds of studies with school-aged students.

_ _ _ _ _ _

In Part II of the Series, we used the evidence-based Stop & Think Social Skills Program as an exemplar for how to teach students social, emotional, and behavioral self-management through a social skills instructional curriculum.

Initially, we defined Self-Management as a child or adolescent’s ability:

To be socially, emotionally, and behaviorally aware of themselves and others;

To effectively control their emotions, as well as their thoughts, beliefs, expectations, and attributions; and

To behaviorally demonstrate successful interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills.

We then noted that:

On a social level, children and adolescents need to progressively learn the self-management skills that contribute to effective: (a) listening, engagement, and responding; (b) communication and collaboration; (c) social problem-solving and group interactions; and (d) (once again) conflict prevention and resolution.

On an emotional level, they need to learn the self-management skills that result in: (a) the awareness of their own and others’ feelings; (b) the ability to manage or control their feelings and emotions; (c) the ability to cope with the emotional effects of current situations; and (d) the ability to demonstrate appropriate behavior even under conditions of emotionality.

Finally, on a behavioral level, children and adolescents need to learn the self-management skills that help them to be actively engaged in and responsible for their own learning (individually, and in small and large groups), and to demonstrate appropriate behavior in the classroom and across the common areas of the school.

We concluded that existing Mindfulness programs do not adhere to the science-to-practice principles of cognitive-behavioral science or the social skills instructional approaches guided by social learning theory.

_ _ _ _ _

In Part III of the Series, we reviewed (a) an October 11, 2017 article in Scientific American (“Where’s the Proof that Mindfulness Meditation Works?”) that referenced (b) an article published the day before in Perspectives on Psychological Science, and (c) yet another Scientific American article (“Mindfulness Training for Teens Fails Important Test”) that was published on October 31, 2017.

The latter article began as follows:

“Over the past several decades, the practice of mindfulness has evolved into a booming billion-dollar industry, with growing claims that mindfulness is a panacea for host of maladies including stress, depression, failures of attention, eating disorders, substance abuse, weight gain, and pain.

Not all of these claims, however, are likely to be true. A recent critical evaluation of the adult literature on mindfulness identifies a number of weaknesses in the extant research, including a lack of randomized control groups, small sample sizes, large attrition rates, and inconsistent definitions of mindfulness.

Moreover, a systematic review of intervention studies found insufficient evidence for a benefit of mindfulness on attention, mood, sleep, weight control, or substance abuse.

That said, there is empirical evidence that mindfulness offers a moderate benefit for anxiety, depression, and pain, at least in adults.”

[CLICK HERE FOR ARTICLE and OTHER LINKS]

_ _ _ _ _

This article then asked whether Mindfulness can effectively address depression and anxiety in teens. It noted that some research suggests that Mindfulness can be useful, but it again reinforced the critique above regarding the shortcomings in the research.

Finally, the article summarized a large-scale study with 308 middle and high school students in 17 different classrooms across five different schools who were randomly assigned to a Mindfulness training or Control group (published in Behavior Research and Therapy in 2016).

The students receiving Mindfulness training participated in weekly 35 to 60 minute sessions conducted by the same certified instructor, they were encouraged to practice mindfulness techniques at home, and they were given manuals to assist in this practice. All participants were assessed at three different time points with measures of anxiety and depression, weight and shape concerns, well-being, emotional dysregulation, self-compassion, and mindfulness. Baseline measures were taken one week before the intervention, a post-test measure was taken a week after the sessions were over, and a follow-up assessment was administered about 3 months later.

Despite the many outcome measures used, there was no evidence of any benefit for the Mindfulness group based on either the immediate post-test or the follow-up evaluations.

In fact, anxiety was higher at the follow-up for males in the mindfulness group relative to males in the control group. This result also occurred for participants with low baseline depression and weight concerns—the Mindfulness training led to an increase in anxiety for these individuals over time.

This study is notable not just for its insignificant (to slightly negative) outcomes, but because it documents that the significant amount of time needed to implement the Mindfulness program—for both the clinician and the students— largely went for naught.

_ _ _ _ _

Finally on June 2, 2018, we updated our previous discussions—adding a review of some of the Mindfulness curricula being used in some schools.

[CLICK HERE for this Blog Message]

June 2, 2018 Making Mountains Out of Molehills: Mindfulness and Growth Mindsets. Critical Research Questions the Impact of Both

In our introduction, we reminded colleagues that mindfulness was originally popularized by Dr. John Kabat-Zinn with a goal of helping adults cope with stress, anxiety, pain, and illness. Kabat-Zinn integrated meditational practices from the Buddhist tradition with yoga and medical science into a mindfulness-based stress reduction program that was not designed for use with children and adolescents.

A number of national and international groups adapted Kabat-Zinn’s work to schools and students—among them The Inner Kids Program (Los Angeles), MindUP (The Goldie Hawn Foundation), Mindful Moment (The Holistic Life Foundation), Rise-Up (Mindful Schools), and Mindfulness in Schools Program (Great Britain).

But, despite the “home-grown research” cited by some of these groups—to argue the merits and validity of their materials—there are many critical questions.

For example, have they been:

- Independently and objectively validated across. . .

- Multiple randomly-selected communities and school sites, involving...

- Students who are representative of students in schools and communities nationwide?

Moreover, have the participating schools and students been:

- Compared with randomly-selected comparison schools that received the same amount of time and training relative to students’ attention and emotional control (just not through a Mindfulness curriculum). . .

- Evaluated on outcomes using objective, reliable, and valid measures completed by different observers- - including the students themselves. . . where

- These measures were given at least twice before the program was begun, multiple times as the program was implemented, and at least twice (after at least 6 months, and then 12 months) after the program was over?

In other words, have these programs been implemented with fidelity, and objectively evaluated in ways that demonstrated that they produced meaningful results?

Moreover, have their researchers demonstrated that the student-specific results were directly and causally related to the Mindfulness program—and not due to the “special” attention paid to the students involved, to the individuals leading the program and its sessions, or to the way the schools or students were selected?

_ _ _ _ _

Our conclusion in June, 2018 was that:

At this point, the research and practice simply do not support the implementation of Mindfulness programs by any district or its schools.

Even if a district or its schools has “already invested in the training time and materials,” they are still investing instructional time that should be focused on the SAME student outcomes, but with demonstrated, evidence-based multi-tiered practices and strategies.

In other words, we recommended that districts and schools stop throwing good money after a bad investment.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Mindfulness Research Update

It is not my goal here to provide an in-depth methodological analysis of the most-current sound, objective, and quasi-experimental studies investigating the efficacy of mindfulness programs or interventions with school-aged students.

At the same time, in preparing for this Blog message, I did review the research, and I found very few methodologically-sound studies published since my June, 2018 Blog (see Blog citation above).

One important article, published in the journal Mindfulness in 2019, reviewed many of the studies that I also found. Authored by McKeering and Hwang, the article is titled, “A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-Based School Interventions with Early Adolescents.”

[CLICK HERE for original article]

In their research, these authors reviewed nine electronic databases that identified 1,571 studies discussing mindfulness with early adolescents. After evaluating the quality of the research methodologies in these studies, only 13 studies met their criteria for sound research. That’s less than 1% of the studies assessed.

This, once again, demonstrates that—just because a study on mindfulness appears in a “professional” journal—this does not mean that the study and its stated results and conclusions are valid.

This is also important because, according to McKeering and Hwang, “(t)he review found positive improvements reported in well-being measures in 11 of the 13 papers.”

But our story does not end here.

While we appreciate the good work of these authors, we must note that psychological or psychoeducational interventions are most useful when their successes are sustained either (a) without the need for continued intervention sessions, or (b) after the intervention sessions have been discontinued.

Methodologically, this is tested when studies evaluate the impact of an intervention (a) immediately after it has been fully implemented; and then (b) after another six, twelve, or eighteen months—where no additional intervention training has occurred. When studies only do (a) above, they are called “pre-post” studies. When they do both (a) and (b), they are called “pre-post-post” studies.

Critically, of the 13 papers that McKeering and Hwang “certified” as using sound research methods, the Table summarizing these studies in their article indicated that:

- Only four of the studies used pre-post methods;

- Only three additional studies used pre-post-post methods; and

- None of the studies used “multi-respondent, multi-instrument, and multi-setting methods.

Of the three pre-post-post studies, two collected their second “post” data only three months after the first set of post data were collected, and the other one did not specify when it collected its follow-up “post” data.

Thus:

- None of the “methodologically-sound” studies truly used sound research methods, and

- Any conclusions regarding the impact (relative to changing student behavior) or usefulness (relative to sustaining changed behavior) of these articles’ mindfulness approaches either were not be determined or are not present.

This conclusion is further strengthened by the fact that none of the studies used multi-respondent, multi-instrument, and multi-setting methods.

That is, they did not evaluate the impact of the mindfulness interventions using (a) multiple respondents (e.g., students and teachers); (b) multiple assessment instruments (e.g., student self-report, teacher behavior ratings, classroom observation, and physiological measurements); and (c) in multiple settings across the school (e.g., in different classrooms, and different common school areas—where many stressful situations for students occur).

Thus, based on McKeering and Hwang’s recent study, 1,571 originally-identified studies were reduced to 13 studies, that we subsequently reduced to zero methodologically-sound studies.

The implication? Schools need psychological and psychoeducational interventions that are sustained (largely by the students themselves) over long periods of time—without the need for continuous teacher or mental health professional monitoring or involvement. When students cannot sustain their initial intervention progress or success over time, these benefits typically are lost, because school personnel simply can’t keep up with them in the face of other, more essential priorities.

_ _ _ _ _

The McKeering and Hwang study reinforced an October 19, 2017 article by Brian Resnick. In Is Mindfulness Meditation Good for Kids? Here’s What the Science Actually Says, Resnick noted that in 1970 there were no professional journal and no newspaper stories discussing “mindfulness.”

In 2015, he counted 1,200 professional journal, and 32,000 newspaper stories on “mindfulness.” But he noted that very few of the professional journal articles involved school-aged students, and virtually all of the newspaper stories had more to do with “public interest” than research-based assertions.

Indeed, Resnick concluded his article by saying that “the evidence for mindfulness in adults is limited, but promising.”

Relative to school-aged students, he stated:

I found only three recent systematic reviews on the use of mindfulness and mediation practices in schools. . . (T)hey generally find positive results, but note methodological flaws in the literature. . .

Because mindfulness sessions are composed of a grab bag of activities—concentrating on breathing, concentrating on sounds, groups discussions of the mind-body connection—it’s hard to know what, exactly, the mechanism for these positive changes is, and if that mechanism is unique to mindfulness . . . And that’s one of the biggest criticisms of mindfulness that I kept encountering in reporting: It’s all kind of vague. Mindfulness—a collection of disparate concentration activities—targets broad regions in the brain and broadly helps people on a number of things.

Overall, there’s evidence that suggests mindfulness has a positive effect for kids on anxiety and cognitive measures. But the research isn’t clear on why, whom it’s most beneficial for. . ., or whether the effect is specific to mindfulness instruction.

Without trying to be unfair, I would like everyone to re-read Resnick’s conclusions above—substituting the made-up word, Mindfulcillin, for Mindfulness. I want you to make believe that Mindfulcillin is a new drug on the market, and that its promos say that it can decrease students’ anxiety and increase their attention and academic productivity.

Given the words or phrases “methodological flaws,” “a grab bag of activities,” “hard to know exactly what the mechanisms for these positive changes are,” and “the evidence suggests a positive effect, but it isn’t clear on why or whom it’s beneficial for” in Resnick’s statement above:

Would any of you allow your eight year old child take this medication?

This is why the Federal Drug Agency exists, and why only drugs that have been scientifically proven to positively impact specific medical problems (with extremely low levels of side effects) are approved and made available to the public.

This is also why these drugs are only prescribed by medical professionals who have been licensed at the state level as competent in their selection and use.

Neither of these conditions are present for Mindfulness—or its Medication correlate.

None of the Mindfulness studies reviewed in the past or currently for this Blog comes close to the scrutiny of a new medication or drug. While we assume that Mindfulness programs are being selected for the schools by well-meaning educators, do they have the training or skills—like our medical colleagues—to make these decisions?

_ _ _ _ _

But There is More: The Selling of Mindful Schools

One of the leading training and distribution mindfulness vendors (and, I am using the word “vendor” very consciously) is Mindful Schools. This company claims to have trained over 15,000 “Certified Mindfulness Instructors” with its full-year certification program currently costing $5,875 (you do the $88 multi-million dollar math !!!).

Significantly, this “program” consists of a 10-month, 300-hour remote program, and two “retreats.”

Thus, there is no live, physical, or direct observation on-site training, clinical practice, supervision and accountability, or objective evaluation of any “Certified Instructors” ability to lead a school in this company’s approaches.

This is basically practicing psychology without a license.

_ _ _ _ _

In looking at the company’s Leadership and Lead Trainers, I saw THREE individuals with doctorates (in Education, Religion, and Social Work)—and NO doctoral-level school, child, or related psychologists.

This multi-million dollar grossing company and its training is largely run by business-people, marketers, and former educators who were involved in a mindfulness program—many at their original “home” schools.

Indeed, in the description for the certification program, the Mindful Schools website states,

“The Mindful Teacher journey is supported by a diverse and interdisciplinary team of highly skilled and experienced teachers working at the intersection of mindfulness and education.”

Thus, one of the “leading” mindfulness training programs in the country is not based on the (school) psychology of learning and cognition, normal and abnormal behavior, social-emotional development and psychology, or developmental and behavioral growth. . . . regardless of the marketing allusions, graphics, descriptions, and diagrams on its website.

_ _ _ _ _

Relative to research, if you click on one of the citations that this company uses to “validate” its training and school implementation program, you get a page with 30 research citations.

These are the same “research” articles that have been reviewed by other authors (see these reviews described earlier in this Blog).

While there are testimonials on their website—in the form of “Implementation Stories,” there are NO studies on the website validating the program or practices being sold by Mindful Schools.

Based on the absence of research validating their own program, it appears that Mindful Schools is selling large doses of “Mindfulcillin” (see my earlier comments).

They are making money, while schools are wasting money that could be dedicated to evidence- and psychologically-based sound practices.

Moreover, their own Senior Program Manager, Oren J. Sofer was quoted in Resnik’s October 19, 2017 article, Is Mindfulness Meditation Good for Kids? Here’s What the Science Actually Says (see our earlier discussion of Resnick’s article) as saying:

“You can overstate the research and make claims that haven’t been validated, but saying that (Mindfulness is) ‘experimental’ I believe is understating the research. I think it’s important to research this stuff, but at the same time, it’s important to have common sense. Do we as adults and educators in society have a responsibility to teach children to be self-aware? You don’t need a research study to answer that question.”

Pardon my French but. . . .What a load of self-serving and reprehensible crap.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Connecting the Psychological and Neurological Foundations of Emotional Self-Regulation and Self-Management

If the non-existent research on Mindfulness (and mediation) discussed above is not enough, let’s look at the primary goals of a Mindfulness program alongside the teaching of social, emotional, and behavioral skills, and the neuropsychology of emotions and emotional reactivity.

As noted earlier, one of the goals of a social skills program is to teach students emotional self-management—what some call “emotional self-regulation,” and what others broaden into discussions of “emotional intelligence.”

Critically, my preference is to stick with the term “emotional self-management”—recognizing that this involves instruction in emotional awareness, emotional control, and emotional coping skills, respectively, that translate into students’ overt behavioral skills and interactions. Thus, ultimately, emotional self-management is an observable, behavioral student outcome.

Specifically, emotional self-management consists of a student’s ability to maintain:

- Physiological (relative to adrenaline in the vascular system, and cortisol in the limbic system) control and, hence, emotional control;

- Cognitive self-statement and attributional (relative to attitudes, beliefs, expectations, and self-evaluations) control; and

- Physical behavioral and interpersonal (relative to prosocial interactions, social problem-solving, and conflict prevention) control and execution.

As discussed above, a primary premise of mindfulness and its use of meditation (see the articles cited) is that:

“When students are more aware of their physiological and emotional states, they demonstrate better attention, engagement, and emotional regulation . . . less anxiety, stress, and emotional reactivity . . . and better interpersonal relationships and self-compassion.”

But these claims are inconsistent with both the psychological and neurological foundations of emotional self-regulation and self-management.

Some of the most important scientific foundations here include the following:

- Awareness does not automatically translate into Skill. While awareness can be taught, the social, emotional, or behavioral skills that help students respond to their awareness must also be taught.

- From a psychological perspective, most emotional behavior or reactivity is Classically Conditioned (a la Pavlov).

- From a neurological perspective, most emotional behavior triggers before a student’s conscious awareness or cognitive control over that behavior.

- For all students—but especially those who are emotionally volatile or significantly impacted by trauma—their conditioned emotional responses need to be un-conditioned, re-conditioned, or counter-conditioned. . . and this takes a multi-tiered system of supports that often includes clinically- or therapeutically-intensive interventions.

We briefly discuss each of these scientific foundations—recognizing that they are inconsistent with the cognitive/neocortex-driven foundations of Mindfulness—below.

_ _ _ _ _

Awareness Does Not Automatically Translate into Skill

Relative to self-management, students need to be aware of the need (a) to be in control, (b) to recognize when they are starting to lose control, and (c) to perform specific (physiological, emotional, attributional, and behavioral) strategies or actions to help them succeed.

However: Awareness does not necessarily mean that they have the ability to actually demonstrate needed behaviors, interactions, or skills.

Said a different way: Just because students are socially, emotionally, or behaviorally aware of themselves, others, and what they “are supposed” to in different interpersonal situations, that does not mean that they have the self-management skills to act or interact appropriately.

For example: Just because a student knows how to follow directions, and is aware that they need to be particularly careful to follow directions during a big test. . . that does not mean that they have learned, practiced, and can demonstrate that skill during an actual test. . . especially when excessively stressed (i.e., under conditions of emotionality).

As another example: Just because a student wants to help a peer avoid or escape from a bullying situation, and he or she can envision (i.e., is aware of) what they will say and do, that does not mean that they have the verbal and physical ability to actually do it in “real time”—once again, especially under conditions of emotionality.

_ _ _ _ _

What this all means is that teachers need to teach students—at their appropriate developmental levels—how to be physiologically, socially, emotionally, and behaviorally awareness of themselves and others. This instruction is then extended as students are explicitly taught how to control their physical, emotional, attributional, and behavioral interactions.

Think of it this way: Awareness is represented by a team’s playbook in a particular sport. . . the musical score of an orchestra’s chosen symphony. . . the script—with stage directions—of a theatre group’s next play.

The skill is developed as the team—guided by their coach—practices the plays on the court . . . the orchestra—guided by the conductor—practices the symphony during multiple rehearsals . . . and the theatre group—guided by their director—also rehearse on stage up through their dress rehearsal.

When students can control their emotions, they have a higher probability of thinking through a situation clearly, and then performing the needed interpersonal, conflict prevention, or conflict resolution behavior(s)—if they also have these skills mastered.

If they are unable to control their emotions, their thinking may be muddled, previous learning may be difficult to retrieve or abandoned, and they may emotionally (and behaviorally) over-react or completely shut down.

Once again, teaching students emotional control must be embedded in their social skills instruction, and this instruction must be guided by the age and developmental status of the child or adolescent. But the instruction must also be guided by the physiological and neuropsychological science underlying a student’s (or anyone’s) emotional control.

_ _ _ _ _

Most Emotional Behavior is Classically Conditioned (Pavlov)

We begin this part of the discussion by pointing out that:

Most emotional behavior is conditioned. . . that is, classically conditioned. . . that is, Pavlovian in nature.

To explain: Anyone who has taken Psychology 101 in college knows about Pavlov, and how he conditioned a dog to salivate upon hearing a bell. . . after previously pairing the bell with a piece of meat—a piece of meat that, when presented alone, naturally prompted the dog to salivate.

But let’s put this into human terms.

As adults, are there not others in our lives (perhaps, a current or former significant other) who can immediately trigger an emotion (e.g., anger, irritation, comfort, love) by virtue of their presence, a look, a specific word or phrase, or a verbal intonation?

And when these triggers occur, how quickly do we get emotional?

In most cases, the emotions occur instantaneously. . . involuntarily. . . without thought. . . and without conscious control. That is, the emotional reaction is classically conditioned. It is Pavlovian in nature.

Well, children and adolescents are the same way.

Many of their emotional reactions are classically conditioned, they occur almost instantaneously, and they occur before they have thought (that is, consciously processed in their cerebral neocortex) about what is occurring or how they should react or behave.

The cognitive-behavioral implication of this involves the following:

- If most emotional behavior is conditioned, then we need to condition students’ behavior—for example, during social skills training—so that students are able to involuntarily control their emotions, right from the beginning, in the face of their emotional triggers.

- But if they are already negatively conditioned to certain emotional triggers, the only way to change this conditioning is to un-condition, re-condition, or counter-condition the connection between the trigger and the negative emotional response. This “turns” the negative response into either a neutral or a positive response.

This is consistent from a Pavlovian perspective, and it is similar to a teacher unteaching a student’s incorrectly memorized academic process or algorithm, and then re-teaching the correct one.

_ _ _ _ _

Most Emotional Behavior Neurologically Triggers Before Conscious Awareness or Control

From a neurological perspective, most emotional behavior activates the instinctual part of the brain before activating conscious control and awareness part of the brain.

Said a different way: Students’ (and others’) “fight, flight, or freeze” emotional reactions occur in the reactive mid-brain before the thinking neocortex part of the brain.

While Pavlovian conditioning explains the emotionally-driven behavior that we see in many students, there also is a neurobiological reason for the emotional behavior that we are discussing.

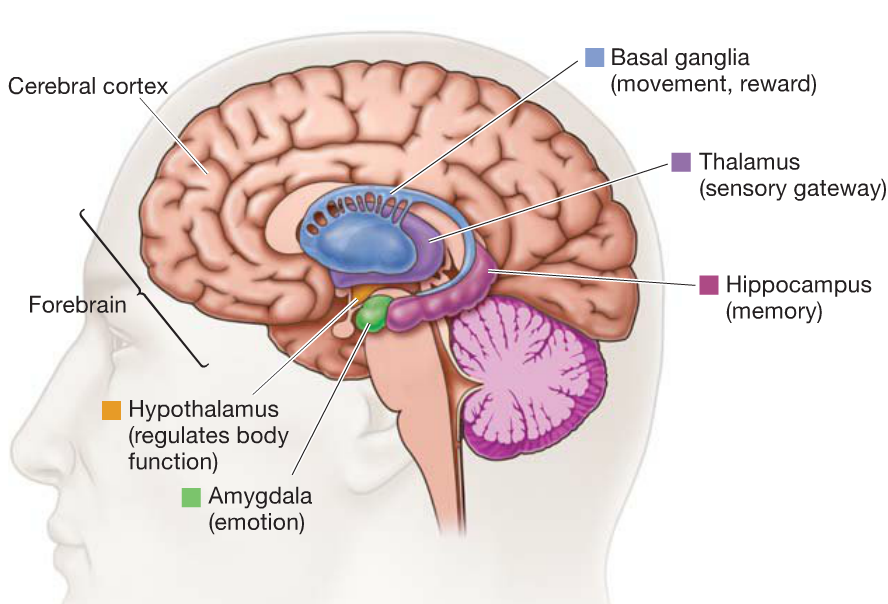

This involves the emotional sequencing between what happens in the temporal lobe of the brain versus the frontal lobes of the brain. More specifically, this involves the reactivity of the amygdala in the temporal lobe, the cerebral cortex in the frontal lobe of the brain, and the thalamus—where all of the sequencing starts (see the Figure below).

Here is the specific sequence whereby the brain processes emotional triggers—determining how and how quickly students react to those triggers:

- The thalamus is a large mass of gray matter in the dorsal part of the diencephalon of the brain. The thalamus has multiple functions, one of which is to act as a relay station, transferring information between different subcortical areas and the cerebral cortex.

Indeed, every sensory system (with the exception of the olfactory system—the sense of smell) has a thalamic nucleus that receives sensory signals and sends them to a related area of the cortex. For example, for the visual system, inputs from the retina are sent to the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, which in turn transfers the stimulus to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe.

- The thalamus also plays an important role in regulating states of sleep and wakefulness, awareness and arousal, and activity or reactivity. Here, the thalamus has many connections to the hippocampus via what is called the mammillothalamic tract, and to the amygdala—both in the temporal lobe of the brain.

- The hippocampus is the brain’s “filing cabinet.” It houses long-term, episodic, recollective, and familiarity memories. The hippocampus is where many traumatic memories are housed—memories that lie dormant until triggered by a sound, word, comparable situation, or even crisis anniversary date.

- The amygdala is the emotional/irrational part of the brain. The amygdala sits right next to, and has direct neural connectivity with, the hippocampus. The amygdala is the center of a student’s conditioned emotional reaction to an external trigger. . . a reaction that often involves a “fight, flight, or freeze” response.

- To put it all together: The information or stimulation (i.e., activation or triggering) of a sense organ is first received by the thalamus. Part of the thalamus' stimuli goes directly to the amygdala, while other parts are sent to the neocortex or the "thinking/rational” part of the brain.

If the amygdala processes a match to the stimulus (that is, if the stimulus matches a memory in the hippocampus) that relates to a previous fight, flight or freeze situation, then the amygdala triggers the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis and “hijacks” or “over-rides” the rational brain—and a conditioned emotional response results.

Critically, the amygdala processes the emotional stimulus milliseconds before the rational brain. So if there is an emotional match in the hippocampus, the amygdala acts before any possible direction from the neocortex can be received.

If, however, the amygdala does not find any match to the external stimulus—relative to previously “recorded” threats—then the neocortex takes over, rationally processes the information, and then designs and executes a plan of action.

The sequence immediately above parallels the earlier Pavlovian explanation as to why “most emotional behavior is conditioned.”

Functionally, the “conditioned response” occurs in the amygdala as the instantaneous fight, flight, or freeze response of a student when under significant, triggered conditions of emotionality.

Given this, as also noted earlier, the only way to alter this conditioning is to un-condition, re-condition, or counter-condition a student’s trigger and response connection using Pavlovian-based training or interventions that, for some students, may need to occur on a clinical, psychotherapeutic level (i.e., with a psychologist).

Critically, when the amygdala perceives a threat, some individuals can react irrationally and destructively—as the conditioned, emotional response takes over the rational, thinking part of the brain.

When this happens, three sequenced reactions to an emotional trigger often occur:

- An individual exhibits a strong emotional and physiological response to the trigger (and the conditioned emotional memory);

- There is a sudden, conditioned reactive (fight, flight, or freeze) behavior; and

- Then there is a post-episode realization that the emotional or behavioral reaction was not warranted or was inappropriate.

This last reaction is the neocortex cognitively “catching up” with the emotional reaction activated by the amygdala.

Said a different way: Initially, the student “acts before s/he thinks.” Later, s/he “thinks about his/her acts.”

_ _ _ _ _

Emotionally Volatile or Trauma-Impacted Students Need More Intensive, Multi-Tiered Interventions

For all students—but especially for those who are emotionally volatile or significantly impacted by trauma—their conditioned emotional responses need to be un-conditioned, re-conditioned, or counter-conditioned. For some students, this requires a multi-tiered system of supports that often includes clinically- or therapeutically-intensive interventions.

Unfortunately, many districts and schools do not have sound research-to-practice multi-tiered systems of support . . . and they are still using the antiquated, unproven frameworks advocated since the “early days of RtI” by the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) and its different National Technical Assistance Centers.

[CLICK HERE to link to Part I of this Blog Series that discusses, for example, the concerns and limitations of OSEP’s PBIS framework]:

Trauma-Informed Schools: New Research Study Says “There’s No Research.” Schools “Hitch-Up” to Another Bandwagon that is Wasting Time and Delaying Recommended Scientifically-Proven Services (Part I)

_ _ _ _ _

[CLICK HERE—and Go to the Bottom on the Page—to Order and Receive the following free monograph:

A Multi-Tiered Service & Support Implementation Blueprint for Schools & Districts: Revisiting the Science to Improve the Practice

_ _ _ _ _

But beyond this, many districts and schools do not have the mental health personnel to address students with more intensive service, support, strategy, and intervention needs (e.g., at the Tier II and Tier III levels), and/or they do not have the mental health personnel with the clinical training, skills, and expertise to address these more intensive needs.

For example, some of the clinical interventions needed for highly or toxically-traumatized students may include:

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation Therapy and Stress Management

- Emotional Self-Management (Self-awareness, Self-instruction, Self-monitoring, Self-evaluation, and Self-reinforcement) Training

- Emotional/Anger Control and Management Therapy

- Self-Talk and Attribution (Re)Training

- Thought Stopping approaches

- Systematic Desensitization

- Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

- Structured Psychotherapy for Adolescents Responding to Chronic Stress (SPARCS)

- Trauma Systems Therapy (TST)

[CLICK HERE—for our October 12, 2019 Blog message on:

The Traps and Trouble with “Trauma Sensitive” Schools: Most Approaches Are Not Scientifically-Based, Field-Tested, Validated, or Multi-Tiered

A National Education Talk Radio Interview (Free Link Included) Puts it All into Perspective

_ _ _ _ _

Summary: Mindfulness versus the Neuropsychological Science of Emotions

Virtually everything about mindfulness and meditation is about awareness, cognitive control and decision-making, and maintaining a level of emotional stability. Thus, virtually everything neuropsychologically about mindfulness is in the cortex and neocortex.

Given this and our discussion above, it should be apparent that:

Virtually all mindfulness programs that emphasize meditation and cognitive control techniques will not prevent the amygdala from activating and, thus, will not prevent students’ fight, flight, or freeze conditioned responses during emotionally-triggering situations.

Moreover, we have yet to see any mindfulness program in this country provide a true, psychologically-based multi-tiered system of support—involving evidence-based clinical/therapeutic interventions for students with significant emotional-behavioral needs.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A Brief Description of Two Evidence-Based Clinical/School Interventions for Students with Significant Trauma-Related Challenges

Two of the evidence-based clinical/school interventions for students with significant trauma-related challenges are Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (C-BITS), and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT). These were noted in the Tier II/III intervention list in the Blog section immediately above.

Below is a brief description of these two approaches.

Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)

CBITS is an intervention program for youth exposed to traumatic events, which can be delivered on school campuses by school-based clinicians. It was developed in collaboration with the Los Angeles Unified School LEA for students and their families. CBITS utilizes individual and group sessions to teach youth relaxation techniques and social problem-solving skills, as well as how to challenge upsetting thoughts and process traumatic memories. CBITS also includes a parent and teacher psychoeducation component.

In a randomized controlled trial comparing this intervention with a three-month wait-list condition, those receiving CBITS reported lower PTSD, depression, and psychological dysfunction symptom scores after three months.

_ _ _ _ _

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

TF-CBT is a short-term individual treatment that involves sessions with the youth and parents as well as parent-only sessions. TF-CBT is for youth aged 4 to 18 who have significant behavioral or emotional problems related to traumatic life events, even if they do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Utilizing weekly clinic-based, individual treatment, TFCBT helps youth process traumatic memories and manage distressing feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. TF-CBT also uses joint parent and youth sessions to provide parenting and family communication skills training.

Compared to a nondirective supportive therapy, sexually abused youth aged 8 to 15 treated with TF-CBT demonstrated significantly greater improvement on levels of anxiety, depression, and dissociation at six-month follow up. Youth treated with TF-CBT also showed a significant improvement in PTSD symptoms and dissociation at 12-month follow-up. Online training for TF-CBT is currently available at www.tfcbt.musc.edu.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary and Recommendations

This two-part Series was dedicated to helping districts, schools, educators, and mental health practitioners understand the research to-practice limitations of (a) trauma-informed programs; (b) trauma-“infused” programs built on the SEL-CASEL or PBIS frameworks; and (in this Blog message—Part II) (c) trauma-focused programs that include mindfulness and meditation programs or approaches.

Critically, readers need to understand the differences between trauma-informed programs and trauma-informed practices.

Part I of this series stated very clearly that (a) there are many students who have experienced trauma-specific events in their lives; (b) these students need to be identified through objective multi-instrument assessments; and (c) these students need specific services, supports, strategies, and interventions—that is, trauma-informed practices—that address the social, emotional, and behavioral effects of these traumas.

[CLICK HERE to link to Blog Message, Part I:

Trauma-Informed Schools: New Research Study Says “There’s No Research.” Schools “Hitch-Up” to Another Bandwagon that is Wasting Time and Delaying Recommended Scientifically-Proven Services (Part I)

But Part I also emphasized that some students exhibit emotional reactions (e.g., “fight, flight, or freeze”) due to emotional triggers that are not trauma-related. In fact, we provided a number of examples of these non-trauma-related emotional triggers.

We also emphasized that ALL students demonstrating high frequency or significantly intense emotional reactions in school need to have their emotional triggers identified through objective and valid multi-instrument assessments.

Next, Part I discussed our concerns with trauma-informed programs—“pre-packaged” programs with many different components and activities that are largely implemented intact and school-wide. We emphasized that virtually all of these programs have not been independently and objectively validated through sound research across multiple settings and circumstances.

Here, we expressed our concerns that some districts and schools are implementing these programs—potentially wasting time, money, and other resources; and potentially delaying appropriate services and supports to students in emotional need, while making their problems worse or more resistant to change.

Finally in Part I, we put our “money where our mouth is”. . . as we summarized a recent study that reviewed over 9,000 other studies, published over the past ten years, that examined trauma-informed school programs.

Using objective, research-sensitive criteria, this study determined that none of the studies they analyzed met their criteria for sound research.

Our conclusion: Our concerns that schools are implementing “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive” programs that have not been objectively validated, do not work, and are counter-productive was supported.

_ _ _ _ _

In this Part II, we discussed the relationship and inappropriate use of mindfulness and mediation with students experiencing trauma. Here, we described (a) the non-existent methodologically-sound or validating research for school-based mindfulness programs; (b) how one popular commercial company—that provides unvalidated mindfulness training to individuals and schools—rationalizes its existence (while making multi-millions of dollars and wasting precious school time and resources); and (c) how the biological and neuropsychological underpinnings of trauma-related student emotionality is inconsistent with the primary goals and desired outcomes of most mindfulness programs, and these programs do not have the multi-tiered psychologically-grounded clinical interventions needed by students with significant social, emotional, and behavioral challenges.

The theme across both Parts of this Series is that:

Districts and schools need to know the Trauma-Informed Care, SEL, Mindfulness, and Meditation research-to-practice as all of these areas have significant flaws that should result in educators questioning their use in schools.

Recognizing that districts and schools do not always have the time or expertise to evaluate the current research-to-practice, we hope that this two-part Series (and my previous Blogs on these topics) will help them to choose effective, multi-tiered approaches to address the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of students impacted both by trauma and by other emotionally-triggering situations, circumstances, and/or conditions.

We also hope to encourage districts and schools that have already adopted and implemented trauma-informed or sensitive programs to objectively and comprehensively evaluate their research, practice, and student-centered outcomes— especially with students who have strategic or intensive clinical needs.

_ _ _ _ _

As I noted in Part I: For my administrative colleagues, if you have committed to a Mindfulness or Growth Mindset “program,” I understand your potential frustration (and cognitive dissonance) in the research and remarks above. While I apologize for the disruption, I cannot change the research.

If you would like to discuss this—or anything related to the success of your students, staff, and school(s)—I am happy to talk with you at any time. Give me a call, or drop me an e-mail.

There are evidence-based and field-tested solutions for students’ social, emotional, and behavioral self-management that are evidence-based, field-tested and proven, and that can be implemented in a short period of time.

This is the perfect time to prepare for your next school year’s successes.

Best,