Disruptive Innovation and Redefining What is Truly Important

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

As I write this week’s Blog, there is no way to avoid or ignore our current sequestered state of affairs.

As of this minute (I just looked at the TV; March 30 at 5 PM EST), there are now over 775,000 worldwide Corona Virus-19 infections confirmed—with more than 37,000 deaths. In the United States, we have over 160,000 infected individuals, and over 3,000 have died. And these numbers are growing every day.

I’m not trying to obsess over the figures. It’s just that there are some who still do not—or have been told not to—believe the figures, or even the significance of this virus. And yet, the World Health Organization received and publicized the first formal report about the virus—and its threat—from China on New Year’s Eve.

[CLICK HERE for U.S. News & World Report article]

Now. . . with pleas (or mandates) to stay at home, to physically distance if we go shopping or engage in other essential activities, and to practice “safe sequestering,” we are all trying to wrap our emotions around this crisis. . . a crisis that is leaving:

- Many children and adolescents confused and concerned (e.g., about their safety and future);

- Many essential workers concerned about day care and the supervision of their children—whose schools have now physically closed;

- Many stay-at-home parents, spouses, and significant others (what I am calling “Partners” in my title) overwhelmed because, for example, 24/7 childcare, home-schooling, and purchasing food and other essential items in short supply have now been added to their usual responsibilities;

- Many (now) “home-at-work” parents trying to balance a new way to work—while also supporting their at-home children, and spouses or significant others;

- Many underemployed or (potentially) unemployed workers anxious about their income and “making ends meet;” and

- Many American children, adolescents, and young through elderly adults, who were already in need, and who are now in greater need. This includes students and adults with disabilities, low income and homeless families, and others who are physically, emotionally, or situationally fragile.

In today’s Blog message, I want to address these needs by, hopefully, helping people (a) identify and work through their emotions; (b) analyze and consider how their thoughts and beliefs are helping or hurting; and (c) discuss, choose, and demonstrate the individual, partnership, and family interactions that “fit” their living circumstances, and that are currently most important to growing (yes, growing) through this crisis.

We will focus on home and family, before work. . . growth, instead of survival or paralysis. . . support, instead of isolation or frustration . . . and grace and gratitude, instead of despair.

And this will be facilitated by connecting the theory of Disruptive Innovation to our current “lifestyle sequestration.”

The Goal is to encourage those reading this Blog to use the “disruptive” opportunity, prompted by the COVID-19 crisis, to make one or more changes in our lives—on behalf of ourselves, our children, our partners, or others in our personal and/or professional families.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Why Disruptive Innovation is Relevant to COVID-19

In his 1997 book The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton M. Christensen, a business theorist and management consultant—who coincidentally passed away due to complications from cancer this past January (January 20, 2020), introduced disruptive innovation into the world of business theory.

In short, the theory states that a Disruptive Innovation is an innovation (think personal computers, smartphones, flash drives)—usually developed by an entrepreneur or someone working outside the mainstream network of industries for a specific product—that so disrupts the existing market that it redefines, transforms, and quickly dominates that market.

Beyond its original applications to business and economics, disruptive innovation is now used more generically to describe anything that disrupts and changes how a complex system acts, interacts, or responds to a completely unique product or set of circumstances.

_ _ _ _ _

In this latter context, I would like to suggest that the COVID-19 virus is an innovative disruption as it has changed our personal and professional lives already in innumerable ways.

The question is:

Will the impact of COVID-19 motivate us to change (i.e., innovate) in positive, proactive, and productive ways—individually, within our families, at our (virtual) workplaces, and across our communities?

OR

Will we resist change—for example, because of arrogance, misinformation, selfishness, resistance, or emotional paralysis?

_ _ _ _ _

While he was a successful businessman, who taught for many years at Harvard Business School, Christensen wrote ten books. For my colleagues in education, one was called Disrupting Class (2008). It discussed the root causes of why schools struggles, and how to overcome these struggles.

But, today, I want to call attention to a somewhat unique article written by Christensen in July-August 2010 in the Harvard Business Review, titled “How Will You Measure Your Life.”

While summarizing its most salient points below, I really encourage everyone to completely read this timeless article—as I believe its message and wisdom are essential to helping us (as above) to positively, proactively, and productively innovate— emotionally, attitudinally, and behaviorally—through the current COVID-19 situation.

Indeed, if we view this current situation as a “disruptive opportunity” to innovate, re-think, re-commit, and re-energize what is truly important in our lives, we will emerge—both during and after this crisis—stronger and healthier in important and life-changing ways.

[CLICK HERE to Link to Article]

_ _ _ _ _

How Will We Measure our Lives During and Because of COVID-19?

Below are five “innovations” that Christensen might connect to the disruptive opportunities within the current COVID-19 crisis.

Christensen Innovation #1: If You Don’t Understand the Science, You Can’t Successfully Change the Practice.

In his 2010 article, Christensen tells the story of how he was given (due to unforeseen circumstances) 10 minutes to explain and apply Disruptive Innovation to the leaders at Intel. After explaining that he needed 30 minutes to explain the model, his talk was interrupted two or three times by the presiding Chairman of Intel who told Christensen that “he got it. . . Just tell us what it means for Intel.”

After resisting the pressure to bypass the science underlying the theory, Christensen finished discussing the theory— providing a market-relevant (to Intel) example. Because he now understood the theory, the Chairman of Intel eventually applied it accurately, making an important strategic, disruptive, and financially lucrative decision for Intel and how it proceeded to manufacture computer chips.

In Christensen’s words:

When I finished the mini-mill story, Grove (the Chairman of Intel) said, “OK, I get it. What it means for Intel is…,” and then went on to articulate what would become the company’s strategy for going to the bottom of the market to launch the Celeron processor.

I’ve thought about that a million times since. If I had been suckered into telling Andy Grove what he should think about the microprocessor business, I’d have been killed. But instead of telling him what to think, I taught him how to think—and then he reached what I felt was the correct decision on his own.

That experience had a profound influence on me. When people ask what I think they should do, I rarely answer their question directly. Instead, I run the question aloud through one of my models. I’ll describe how the process in the model worked its way through an industry quite different from their own. And then, more often than not, they’ll say, “OK, I get it.” And they’ll answer their own question more insightfully than I could have.

Implication #1. None of us truly knows what happens in others’ homes, relationships, or lives. Thus, telling people what they “must” do at home to respond effectively to COVID-19 will likely fail.

Instead, we are better off describing the values, principles, priorities, and some examples of actions that can help most people to balance and respond to (a) the personal and professional (emotional and real) demands of the COVID-19 situation; and (b) the community, state, national, and global responsibilities that we all have to help subdue this virus as quickly as possible.

At this point, short of violating curfews and laws, we should then let our friends and colleagues decide how they want to uses these principles and practices. In most cases, like the Intel Chairman, if they understand it, they will apply the “theory” well.

Recommendation #1. An important need right now is to establish and maintain realistic schedules during the day at home. . . schedules for ourselves, our children, and our significant others. These schedules provide ongoing structure and predictability. . . which helps with physical health and emotional stability.

As these schedules are crafted, it is important to discuss choices and options with family members, and to recognize that—due to additional and unforeseen disruptions, flexibility needs to be woven into the structure.

Bottom Line: We need to practice and maintain realistic, but fluid, expectations.

We also need to understand that, given our current conditions, we can expect that we may not always know what to expect.

_ _ _ _ _

Christensen Innovation #2: If You Don’t Know Where You’re Going, Any Road will Get You There.

Using editorial license, this Lewis Carroll quote from Alice in Wonderland suggests that we are most successful when we live purposeful lives.

In a February, 2014 Huffington Post article, Yogi Cameron Alborzian identified “The 5 Habits of Purposeful People.” These were:

- Habit #1: Live in the present moment.

- Habit #2: Focus on one thing.

- Habit #3: Make changes today, not tomorrow.

- Habit #4: Be of service to others.

- Habit #5: Practice.

In his article, Christensen tells of how he always asks his Harvard Business School students to answer three questions before they graduate:

- How can I be sure that I’ll be happy in my career?

- How can I be sure that my relationships with my spouse and my family become an enduring source of happiness?

- How can I be sure I’ll stay out of jail?

[Christensen asked this last question, because two of the 32 students in his Rhodes scholar class spent time in jail, and because Jeff Skilling of Enron fame was his classmate at Harvard Business School. Acknowledging that “These were good guys—but something in their lives sent them off in the wrong direction”. . . Christensen felt compelled to encourage his students to plan for their own honesty, integrity, and morality.]

Relative to the first two questions, Christensen’s personal belief was that family and relationships should come before job and money. This focus might help us to re-contextualize the current COVID-19 sequestration situation where many of us are at home, with family, but also now working.

In Christensen’s words:

When I was a Rhodes scholar, I was in a very demanding academic program, trying to cram an extra year’s worth of work into my time at Oxford. I decided to spend an hour every night reading, thinking, and praying about why God put me on this earth. That was a very challenging commitment to keep, because every hour I spent doing that, I wasn’t studying applied econometrics. I was conflicted about whether I could really afford to take that time away from my studies, but I stuck with it—and ultimately figured out the purpose of my life.

Doing deals doesn’t yield the deep rewards that come from building up people. . . Your decisions about allocating your personal time, energy, and talent ultimately shape your life’s strategy.

I have a bunch of “businesses” that compete for these resources: I’m trying to have a rewarding relationship with my wife, raise great kids, contribute to my community, succeed in my career, contribute to my church, and so on. And I have exactly the same problem that a corporation does. I have a limited amount of time and energy and talent. How much do I devote to each of these pursuits?

Allocation choices can make your life turn out to be very different from what you intended. Sometimes that’s good: Opportunities that you never planned for emerge. But if you mis-invest your resources, the outcome can be bad. As I think about my former classmates who inadvertently invested for lives of hollow unhappiness, I can’t help believing that their troubles relate right back to a short-term perspective.

When people who have a high need for achievement—and that includes all Harvard Business School graduates—have an extra half hour of time or an extra ounce of energy, they’ll unconsciously allocate it to activities that yield the most tangible accomplishments. And our careers provide the most concrete evidence that we’re moving forward. You ship a product, finish a design, complete a presentation, close a sale, teach a class, publish a paper, get paid, get promoted.

In contrast, investing time and energy in your relationship with your spouse and children typically doesn’t offer that same immediate sense of achievement.

Kids misbehave every day. It’s really not until 20 years down the road that you can put your hands on your hips and say, “I raised a good son or a good daughter.” You can neglect your relationship with your spouse, and on a day-to-day basis, it doesn’t seem as if things are deteriorating. People who are driven to excel have this unconscious propensity to underinvest in their families and overinvest in their careers—even though intimate and loving relationships with their families are the most powerful and enduring source of happiness.

If you study the root causes of business disasters, over and over you’ll find this predisposition toward endeavors that offer immediate gratification. If you look at personal lives through that lens, you’ll see the same stunning and sobering pattern: people allocating fewer and fewer resources to the things they would have once said mattered most. . .

Ultimately, people don’t even think about whether their way of doing things yields success. They embrace priorities and follow procedures by instinct and assumption rather than by explicit decision—which means that they’ve created a culture.

In using this model to address the question, “How can I be sure that my family becomes an enduring source of happiness?”, my students quickly see that the simplest tools that parents can wield to elicit cooperation from children are power tools. But there comes a point during the teen years when power tools no longer work. At that point parents start wishing that they had begun working with their children at a very young age to build a culture at home in which children instinctively behave respectfully toward one another, obey their parents, and choose the right thing to do. Families have cultures, just as companies do. Those cultures can be built consciously or evolve inadvertently.

If you want your kids to have strong self-esteem and confidence that they can solve hard problems, those qualities won’t magically materialize in high school. You have to design them into your family’s culture—and you have to think about this very early on. Like employees, children build self-esteem by doing things that are hard and learning what works.

Implication #2. While I do not want to stereotype, for families with children who are now “home from school,” Christensen’s focus on putting the family first is now self-evident.

- For single parents who are working at home or still working at a job site, the safety and supervision of the children at home or at daycare—because they are not physically at school—takes precedence.

And employers will need to understand this and make appropriate concessions or accommodations.

- For single parents who are now unemployed and at home, the focus first on the children is essential—even though the emotional and financial stress may be immense.

- For the one- or two-parent working families, where one parent is still working outside the home and the children are now home from school, the two parents will need to collaborate on how to support the parent now (still) at home during the day, and how to share this support when the working spouse or partner comes home from work.

- And for the two-parent working families where both parents are home alone with the children, much of what Christensen said above—relative to the short-term pay-offs from work versus the long-term pay-offs for family—hold fast.

Recommendation #2. Christensen notes the importance of designing a family culture. Now more than ever, this culture needs:

- To be explicitly defined, planned, discussed, behaviorally implemented, and periodically evaluated and debriefed;

- To be tailored the four (or other) sample family configurations described immediately above;

- To begin with the parent(s), partners, and/or significant others (or caretakers); and then

- To involve the children through discussions that are sensitive to what they can developmentally understand, and that encourage their active participation.

During these discussions, parent(s), partners, and/or significant others need to: (a) identify negotiables and non-negotiables; (b) address how to avoid, diffuse, and resolve conflicts; and (c) recognize that emotions may sometimes undermine common sense. . .

Mistakes will occur, but they can be overcome.

Once again, Alborzian’s “5 Habits of Purposeful People” can be a guide:

- Habit #1: Live in the present moment.

- Habit #2: Focus on one thing.

- Habit #3: Make changes today, not tomorrow.

- Habit #4: Be of service to others.

- Habit #5: Practice.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

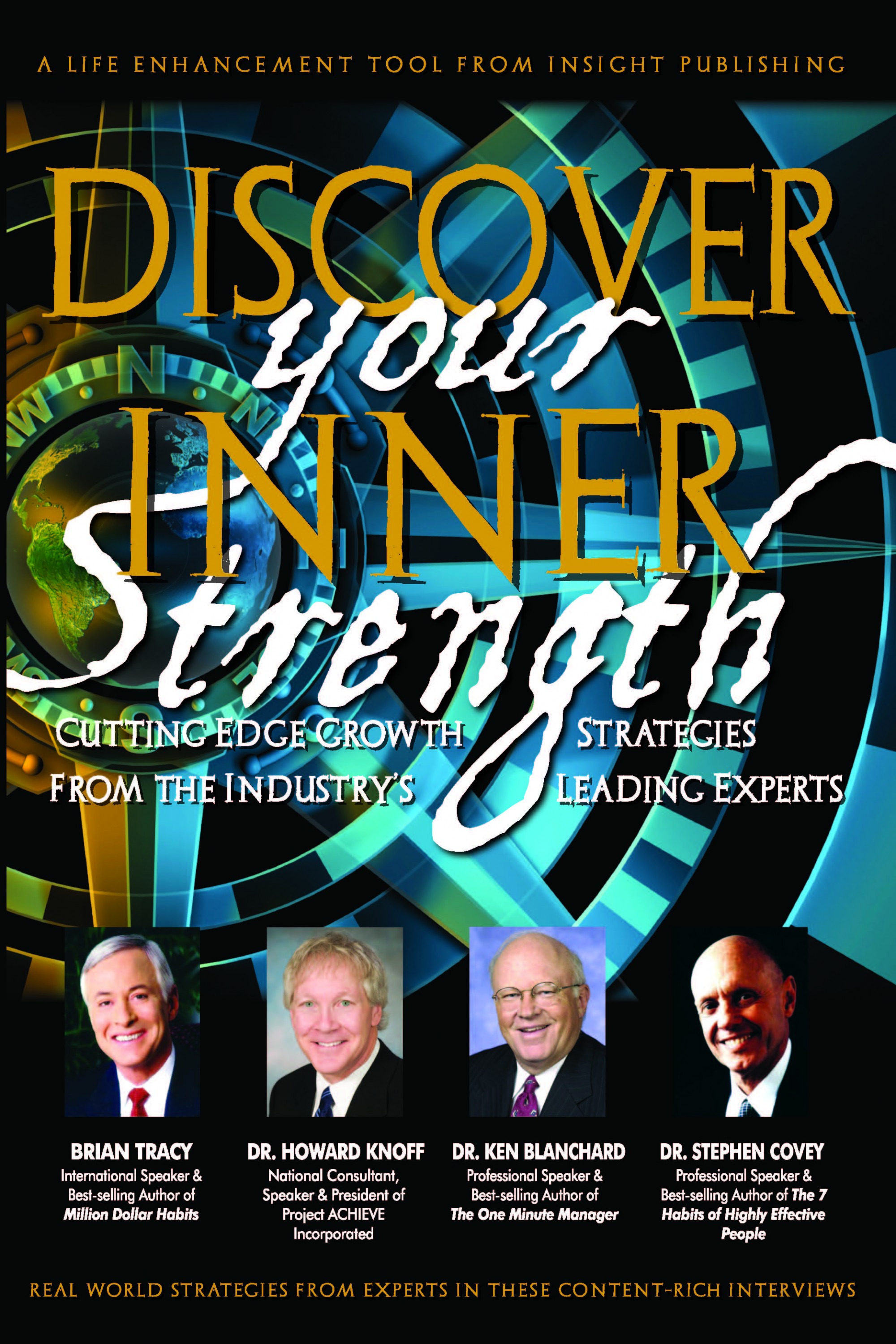

Watch this Video for a Special Offer on our best-selling book: Discover Your Inner Strength

To review my book (or order for Shipping & Handling only):

Discover Your Inner Self

Edited by Brian Tracy, Ken Blanchard ("The One Minute Manager"),

Stephen Covey ("The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People), and Howie Knoff

CLICK HERE

(The book is in the Middle of the Second Line)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Christensen Innovation #3: Understand the Difference Between Consistency and Common Sense.

It is important to recognize the need to be consistent relative to our principles and values, our beliefs and expectations, and the family climate and culture that we want to create and sustain.

At the same time, while consistency is important, there are times—especially when under “conditions of emotionality”—that we need to choose our battles, take a “time-out,” and reconnect later. There are other times when we need to “agree to disagree,” and simply “let it go” and move on.

Said a different way: There is a time for consistency, and some times when common sense should rule. So long as common sense does not undermine the consistency of our principles and values, we have not lost.

In Christensen’s words:

We’re taught in finance and economics that in evaluating alternative investments, we should ignore sunk and fixed costs, and instead base decisions on the marginal costs and marginal revenues that each alternative entails.

Unconsciously, we often employ the marginal cost doctrine in our personal lives when we choose between right and wrong. A voice in our head says, “Look, I know that as a general rule, most people shouldn’t do this. But in this particular extenuating circumstance, just this once, it’s OK.”

The marginal cost of doing something wrong “just this once” always seems alluringly low. It suckers you in, and you don’t ever look at where that path ultimately is headed and at the full costs that the choice entails. Justification for infidelity and dishonesty in all their manifestations lies in the marginal cost economics of “just this once.”

I’d like to share a story about how I came to understand the potential damage of “just this once” in my own life. I played on the Oxford University varsity basketball team. We worked our tails off and finished the season undefeated. The guys on the team were the best friends I’ve ever had in my life. We got to the British equivalent of the NCAA tournament—and made it to the final four.

It turned out the championship game was scheduled to be played on a Sunday. I had made a personal commitment to God at age 16 that I would never play ball on Sunday. So I went to the coach and explained my problem. He was incredulous. My teammates were, too, because I was the starting center. Every one of the guys on the team came to me and said, “You’ve got to play. Can’t you break the rule just this one time?”

I’m a deeply religious man, so I went away and prayed about what I should do. I got a very clear feeling that I shouldn’t break my commitment—so I didn’t play in the championship game.

In many ways that was a small decision—involving one of several thousand Sundays in my life. In theory, surely I could have crossed over the line just that one time and then not done it again. But looking back on it, resisting the temptation whose logic was “In this extenuating circumstance, just this once, it’s OK” has proven to be one of the most important decisions of my life.

Why?

My life has been one unending stream of extenuating circumstances. Had I crossed the line that one time, I would have done it over and over in the years that followed.

The lesson I learned from this is that it’s easier to hold to your principles 100% of the time than it is to hold to them 98% of the time. If you give in to “just this once,” ... you’ll regret where you end up. You’ve got to define for yourself what you stand for and draw the line in a safe place.

Implication #3. We are now living under extenuating circumstances. While these circumstances are taxing and stressful, we need to be mindful of making a 2% allowance—personally, professionally, within our family, and with our friends—that will haunt us when this crisis is over.

Recommendation #3. In stressful times, emotions impact our thoughts, beliefs, and expectations (i.e., our attributions), and these two (our emotions and attributions) collectively affect our behavior and interactions.

The same is true of our significant others—including our children and adolescents. They, too, have their own emotions and attributions. And for our children and adolescents, they are going to emotionally experience and cognitively understand our current COVID-19 world in ways that are developmentally different from us.

Some will feel fear. . . anxiety. . . a loss of control. . . frustration. . . anger. Some will internalize these emotions, while others will externalize them. Some will be OK, while others will be on edge. Some will lose sleep (often bringing them closer to the emotional edge), and others will become more animated or more needy.

For your children and adolescents, when under crisis and “close quarter” circumstances, the only norms are their norms.

But remember that their norms can mirror the norms that you establish and practice.

Work to support the feelings of everyone in your family, while sharing your own emotions through positivity and strength. Be consistent, but use common sense.

Remember: Stephen Covey talks about “Beginning with the End in Mind.”

But he also says that to accomplish this end, we need to “Put First Things First”. . . to “Be Proactive,” to “Think Win-Win,” and to “Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood.”

_ _ _ _ _

Christensen Innovation #4: Remember the Importance of Humility.

If there is anything to learn from the COVID-19 virus, it is that there are forces (even microscopic forces) that are larger and more powerful than we will ever be.

And so, while we have all (I hope) shown humility under different life circumstances, this crisis necessarily humbles all of us.

As discussed above, the question is, “How will we handle it?” Will we handle it with grace, gratitude for our blessings, and honor? Or will we handle it with resentment, selfishness, and dishonor?

In Christensen’s words:

I was asked to teach a class on humility at Harvard College. I asked all the students to describe the most humble person they knew.

One characteristic of these humble people stood out: They had a high level of self-esteem. They knew who they were, and they felt good about who they were. We also decided that humility was defined not by self-deprecating behavior or attitudes but by the esteem with which you regard others.

Good behavior flows naturally from that kind of humility. For example, you would never steal from someone, because you respect that person too much. You’d never lie to someone, either.

It’s crucial to take a sense of humility into the world. . . (I)f your attitude is that only smarter people have something to teach you, your learning opportunities will be very limited. But if you have a humble eagerness to learn something from everybody, your learning opportunities will be unlimited.

Generally, you can be humble only if you feel really good about yourself—and you want to help those around you feel really good about themselves, too. When we see people acting in an abusive, arrogant, or demeaning manner toward others, their behavior almost always is a symptom of their lack of self-esteem. They need to put someone else down to feel good about themselves.

Implication #4. There are lessons in this pandemic. . . and many possible “silver linings.” But we have to have the willingness. . . the self-confidence. . . the self-deprecation. . . indeed, the humility. . . to seek these lessons out. We also need to trust and realize that these lesson may be hidden right now from us.

Recommendation #4. I am currently taking an on-line course from Tony Robbins and Dean Graziosi. It’s actually a pretty cool course as it integrates personal growth with business development and giving back to others.

At the very beginning of the course, Dean talks about the importance of beginning and ending every day by reviewing what we are grateful for, why we are grateful, and what we have accomplished during the past 24 hours—regardless of how small or how hidden.

At the present time, when we are dealing with forces that (right now) are larger than ourselves, we need to “be present” and take control of our emotions and our thoughts. We can (learn to) control our emotions, our thoughts, our grace, and our gratitude.

And by controlling these, we can be exemplary models for our children and our significant others. . . so that, collectively, we all can learn from this situation together, and emerge stronger, more whole, and more unified.

_ _ _ _ _

Christensen Innovation #5. Choose the Right Yardstick.

As a psychologist, I know that it is important to measure our short- and long-term outcomes, and that our evaluation tools need to be sensitive enough to accurately measure these outcomes.

But in a crisis, our “typical” social, emotional, behavioral, interpersonal, and productivity goals need to be modified and recalibrated. Indeed, like the emergency room physician, they need to focus first on crisis-management and stabilization. . . before focusing on the surgery that “gets us back on feet.”

Given this, our “yardstick” for success also needs to be modified in a crisis. While we still need to have “high and realistic expectations,” the expectations or “definitions of success” have now changed.

In Christensen’s words (fully 10 years before he actually passed away):

This past year I was diagnosed with cancer and faced the possibility that my life would end sooner than I’d planned. Thankfully, it now looks as if I’ll be spared. But the experience has given me important insight into my life.

I have a pretty clear idea of how my ideas have generated enormous revenue for companies that have used my research; I know I’ve had a substantial impact. But as I’ve confronted this disease, it’s been interesting to see how unimportant that impact is to me now. I’ve concluded that the metric by which God will assess my life isn’t dollars but the individual people whose lives I’ve touched.

I think that’s the way it will work for us all. Don’t worry about the level of individual prominence you have achieved; worry about the individuals you have helped become better people. This is my final recommendation: Think about the metric by which your life will be judged, and make a resolution to live every day so that in the end, your life will be judged a success.

Implication and Recommendation #5. For some—me included—it takes a crisis to realize what is really important in life.

Ten years ago, I lost my mother suddenly during a surgery that she should have survived. Fortunately, because we were gathered for Thanksgiving the next day, everyone in my immediate family had flown in “for the holiday” and were present. In fact, we were all already at the hospital, waiting for my mother to emerge from surgery and post-op.

As the time went well past her expected return, we increasingly became concerned. About two hours past, the doctor came in and gave us the bad news, and we then gathered to see my mother (physically) for the last time to say good-bye.

Many lives have already been suddenly lost to COVID-19. . . suddenly, without warning, and (for some) with no opportunity to say good-bye. It is sad, unfair, gut-wrenching.

This is a time when some of our outside world is out of control. Right now, we need to control what we can control.

What part of your physical world can be or is in your control? What part of your emotional, attributional, and behavioral “world” can be or is in your control? And what parts of this control can you share, model, teach, and motivate in others —especially those who have children and/or adolescents?

Listen to Christensen. . .

Think about those whose lives you can touch right now. Think about the individuals you can help right now to become better people.

Knowing that you are probably reading this at home. . . Who is sitting across from you that you can share some of this Blog message with? Who is in a nearby room? Who is just a telephone call or e-mail away?

Start here. . . start now. . . and then repeat.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

The COVID-19 virus has more than disrupted all of our lives, and we are all trying to wrap our thoughts and emotions around this crisis. . . so that we can make decisions and act in the most effective ways for ourselves, our families, our friends, and our colleagues.

In this Blog message, we emphasized the importance of (a) identifying and working through our (and others’) emotions; (b) analyzing and considering how thoughts and beliefs can help or hurt; and (c) discussing, choosing, and demonstrating the individual, partnership, and family interactions that will help us to grow through this crisis.

We focused on putting home and family, before work. . . on growth, instead of survival or paralysis. . . on support, instead of isolation or frustration . . . and on grace and gratitude, instead of despair.

We did this by modifying Christensen’s theory of Disruptive Innovation to our current “lifestyle sequestration,” and by asking two questions:

Will the impact of COVID-19 motivate us to change (i.e., innovate) in positive, proactive, and productive ways—individually, within our families, at our (virtual) workplaces, and across our communities?

OR

Will we resist change—for example, because of arrogance, misinformation, selfishness, resistance, or emotional paralysis?

Moreover, the Ultimate Goal was to encourage us to use the “disruptive” opportunity to make one or more changes in our lives—on behalf of ourselves, our children, our partners, or others in our personal and/or professional families.

_ _ _ _ _

Through Christensen’s 2010 article, “How Will You Measure Your Life,” five innovations were discussed:

- Christensen Innovation #1: If You Don’t Understand the Science, You Can’t Successfully Change the Practice.

- Christensen Innovation #2: If You Don’t Know Where You’re Going, Any Road will Get You There.

- Christensen Innovation #3: Understand the Difference Between Consistency and Common Sense.

- Christensen Innovation #4: Remember the Importance of Humility.

- Christensen Innovation #5. Choose the Right Yardstick.

These innovations were supplemented by Alborzian’s “5 Habits of Purposeful People”:

- Habit #1: Live in the present moment.

- Habit #2: Focus on one thing.

- Habit #3: Make changes today, not tomorrow.

- Habit #4: Be of service to others.

- Habit #5: Practice.

In the end, the final question is, “What action are you prepared to take now?” Address one of the present needs discussed in this Blog. Prioritize and focus on one at a time. Start today so that you can positively impact others. And, plan and practice your steps. . . and make them a reality.

Good luck!

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Virtual Study Groups Now Forming

While I, too, am working from home, please know that I am always happy to hear from you. . . feedback, critique, questions, and needs.

In addition, I am in the process of putting together two separate monthly, virtual PLC Groups:

- One for Administrators who are interested in learning (and sharing) how to bring their schools or districts--organizationally, professionally, and interpersonally--to the next level of excellence relative to student, staff, and systems outcomes; and

- One for School Psychologists, Counselors, Social Workers, and Special Education Teachers who are interested in learning (and sharing) ways to broaden their roles, work smarter, and have a greater impact on their colleagues (including administrators).

These virtual, videostreamed PLCs (at least one hour per month--with the availability to view the sessions on "tape delay," will give you practical strategies on how to be more successful professionally (and personally), allow you to set the agenda to meet your needs each month, and to share your successes (and frustrations) with an eye toward anchoring these successes (and overcoming these frustrations).

If you are interested in either of these groups, please contact me immediately via e-mail: knoffprojectachieve@earthlink.net .

_ _ _ _ _

Finally, to those of you who have become “first responders” for your students, I simply want to say, “THANK YOU.”

I am fully aware of the efforts you are making on behalf of your students, families, and community. They are not going unnoticed.

Be safe everyone! Think about the opportunities that this challenge presents to us.

Best,

Howie

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Once again, to review my book (or order for Shipping & Handling only):

Discover Your Inner Self

Edited by Brian Tracy, Ken Blanchard ("The One Minute Manager"),

Stephen Covey ("The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People), and Howie Knoff

CLICK HERE

(The book is in the Middle of the Second Line)