Analyzing, Understanding, and Changing Extreme Behavior: In the Capitol and In the Classroom

It’s Never as Easy as We Think or Want

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Less than a week into the New Year, I was hoping to turn the proverbial page and leave all of the trials and tribulations of 2020 in the rearview mirror like a breath of fresh air (sorry for all the idioms). I wanted this Blog message to be upbeat, optimistic, profound, and inspiring.

But after watching an emotionally-fueled mob breech, ransack, and defile our U.S. Capitol and threaten our Constitutional security, I sat desperately watching the live events trying both to process the reality of the scenes, and to make some sense of it.

It was one of the most helpless moments in my life.

In fact, I said to my wife, “I’m a psychologist. Surely, we should be able to figure out the root causes of this situation so that we can prevent similar ones in the future.”

The situation on Wednesday in Washington, D.C. was made worse when I scanned the diverse reactions on social media (including LinkedIn—which is supposed to focus on profession and progress, not personal pronouncements and politics). There, I found “colleagues” rationalizing, reinforcing, condoning, and celebrating the same extreme positions (albeit in writing) embodied in the antagonists who had overtaken and were paramilitarily occupying the Halls of Congress.

These individuals are not patriots (I am deliberately NOT capitalizing this word here).

But I’m not being naïve here either.

Clearly, these significant gaps in ideological, political, and personal beliefs have existed for a long period of time. . . even as they have escalated this past year or more.

But let’s be clear.

Regardless of the rationale or root causes, lawless behavior cannot be tolerated. And, consequences (or, in some cases, punishments) are necessary. Moreover, direct and proportionate actions need to be taken to prevent such behavior in the future.

From a psychological perspective, these actions need to include analysis, intervention, and—ultimately—change. And these actions, through strategic or intensive interventions, should result in changing, over time, the emotions, attributions, and behaviors of the responsible party(ies).

But this “change” must also occur in our classrooms—now and for the future.

We need to help all students, at their current developmental levels, understand the events of the past week. And we need to build (and build onto existing) instruction and supports to strengthen the civic and social, emotional, and behavioral skills of our next generations so that the integrity of our nation is secure.

In this Blog message, I will briefly outline some of the dynamics and possible root causes behind what occurred a few days ago. I will focus on the psychological aspects of the situation—consciously (and, perhaps, simplistically) side-stepping some of the important historical, cultural, and sociological contexts and contributing factors.

For my colleagues in education and mental health, know that this same outline can be applied to school-aged students who demonstrate similar anti-social interactions in the classroom, across your common school areas, and outside of school—including on-line and through social media.

I will end by sharing some resources that are available to begin the school-level discussion in our classrooms. . . to help our students process this week’s affront to the integrity of our country and our democracy.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Root Causes and Contributions to Extreme Behavior

Extreme behavior, across an entire group or population of individuals, does not have one root cause. Thus, understanding and changing extreme behavior on an individual level requires separate, idiosyncratic analyses.

Even here, and typically, there are multiple factors involved, and the intervention and change process often blends “science and art”—that is, research-based approaches that are innovatively applied to sometimes unique situations by professionals with high levels of experience.

Underlying this blend are causal and correlational (or contributory) factors.

During a functional assessment or root cause analysis, these two groups of factors are framed as hypotheses that explain why targeted, extreme behaviors occur. These hypotheses are then assessed in an objective, data-driven way such that they are confirmed, partially confirmed, or rejected. Once the underlying reasons for extreme behavior are validated, they are directly linked to high probability of success services, supports, strategies, and/or interventions for implementation.

Among the most prominent causal factors for extreme behavior:

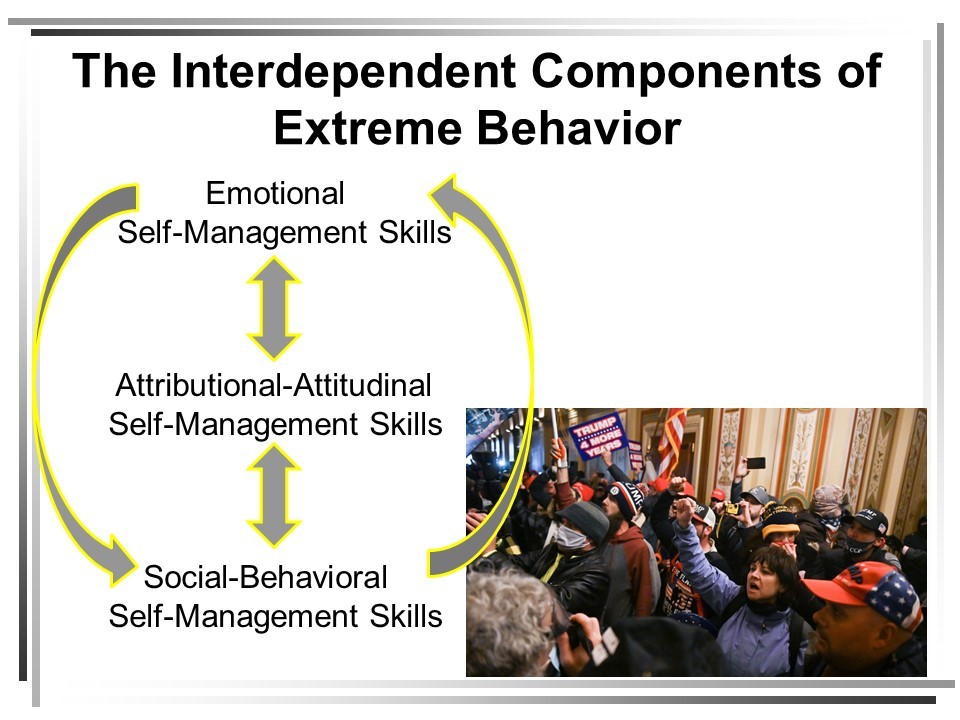

- Factor 1. The interdependent interactions between an individual’s (a) feelings and emotions; (b) beliefs, attitudes, expectations, or attributions; and (c) behaviors or social-interpersonal interactions (see the Figure below).

Because these components are interdependent, the pathways among the three components need to be disaggregated. Below are some examples of some possible pathways that all can lead to extreme behavior.

An Attribution to Emotion to Extreme Behavior Pathway. Someone, for example, could believe (or be told) that something has been taken or stolen from them, or that they have been denied something because of someone else. These beliefs could then trigger frustration, anger, or feelings of loss. . . and/or a need for revenge or to take action. This emotion and misguided motivation may then trigger extreme behavior.

A Behavior to (Attribution or Emotion) back to Extreme Behavior Pathway. Or, someone could actually lose something significant in their lives (a job or promotion, their health or health insurance), that causes them to become emotional or to (irrationally) blame someone else, and this then results in extreme behavior.

An Emotion to Attribution to Extreme Behavior Pathway. Or, someone could have pre-existing anger and emotional control issues that irrationally and perseveratively get “locked onto” specific attitudes or beliefs about a specific person or group that then results in extreme, out-of-emotional control behavior. While somewhat simplistic—and recognizing that outside provocateurs may fuel this fire—this is how racism, antisemitism, bigotry, and xenophobia occurs.

Indeed, at times and for example, some people’s political, religious, and moral beliefs become so narrowly and singularly focused that, when mixed with intolerance toward others who do not share these beliefs, they result in extreme behavior.

NOTE that “extreme behavior” could range along a continuum from extreme internalization to extreme externalization. That is, the behavior could involve withdrawal, isolation, or the refusal to even be in the presence of a person or group of people. Or, the behavior could involve destruction, looting, or murder.

_ _ _ _ _

- Factor 2. Skill Deficits versus Motivational Deficits.

Some (very few) individuals demonstrate extreme acts because they do not have the interpersonal, social problem-solving, objective and rational, conflict prevention or resolution, or emotional control, communication, or coping skills needed to demonstrate appropriate behavior.

These Skill Deficits may occur because the individuals were never taught (or taught appropriately) how to demonstrate these skills, or because they were taught these skills, but never learned, mastered, or learned to apply them—especially under emotional conditions.

_ _ _ _ _

Other individuals have the skills noted above, but they simply choose (or are differentially motivated) to demonstrate extreme behavior.

These Motivational Deficits may include self-motivated acts or acts that are performed for some kind of (actual, anticipated, or promised) external social, tangible, or symbolic reward. Sometimes, these acts are additionally motivated by, for example, a need for attention or adoration (all the way through—in their minds—martyrdom), power or control, validation or social standing, revenge or retribution, or to induce pain or trauma.

_ _ _ _ _

- Factor 3. Some extreme behaviors occur because of neurological, biochemical, and/or biologically-based mental illnesses or disorders.

At the most extreme level, some of these disorders are so significant or pervasive that the individual truly does not have control over their behavior (or a cognitive understanding of the implications of their behavior).

And yet, the emotional, attributional, and behavioral manifestations of many of these disorders can be modified and controlled with medication, clinical intervention, and/or (cognitive-behavioral) therapy.

_ _ _ _ _

Among the most prominent factors contributing to or supporting extreme behavior:

- Factor 1. The Effects of Group Contagion.

From a psychological perspective, Group Contagion is “the spread of a behavior pattern, attitude, or emotion from person to person or group to group through suggestion, propaganda, rumor, or imitation” (The Free Dictionary).

This definition perfectly explains, for some individuals, what we saw leading up to and on the grounds of the Capitol on Wednesday.

And while some individuals were “just observers” who were not behaving violently (for example, some on the balcony just outside the Capitol doors), and while their behavior can be “psychologically understood,” it cannot be excused or condoned.

In fact, the mere physical presence of these individuals contributed to the group contagion effect.

_ _ _ _ _

- Factor 2. Peer Pressure and Deindividuation.

According to Roeckelein and within social psychology circles,

deindividuation refers to a diminishing of one's sense of individuality that occurs with behavior disjointed from personal or social standards of conduct. For example, someone who is an anonymous member of a mob will be more likely to act violently toward a police officer than a known individual. In one sense, a deindividuated state may be considered appealing if someone is affected such that he or she feels free to behave impulsively without mind to potential consequences. However, deindividuation has also been linked to "violent and anti-social behavior."

Facilitating this deindividuation (where it occurred) was the peer pressure experienced by some who participated in Wednesday’s Capitol Hill events, coupled with their need for social affiliation and acceptance.

This was fueled (for some) by the words and actions of our President, and the absolute, referent power that some in the crowd gave to him.

_ _ _ _ _

- Factor 3. Drugs, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse.

Finally, let’s not ignore the potential presence and effects of drugs, alcohol, and substance abuse on individual behavior—even at the extreme level.

There were reports of drug use by some of the insurrectionists when inside the Capitol. While this may have been an act of defiance, note that substance abuse is known to impact one’s thinking and social problem-solving, and to decrease emotional and behavioral inhibition and control.

At an extreme level, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “(c)hronic use of some drugs can lead to both short- and long-term changes in the brain, which can lead to mental health issues including paranoia, depression, anxiety, aggression, hallucinations, and other problems.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary and Applications to the Classroom

The analysis and discussions above are presented for three reasons.

- First, because our ability to understand why extreme acts of behavior occur often helps us to feel less helpless, and more balanced, settled, and in control of our thoughts and emotions.

- Second, our understanding may help identify the services, supports, strategies, or interventions needed to prevent similar extreme acts in the future—and to address these issues more preventatively at the student, school, and systems (including community) levels.

- Third, our understanding may motivate or assist us in helping others to reconcile, recover, or respond to the physical, emotional, or material results of an extreme act.

Clearly, my head is in a “prevention-focused” space right now. I am upset that the acts of sedition on Wednesday were predictable and preventable. While some of the underlying issues are systemic, many of the triggers were premediated and deliberate, and some of the behavior was consciously chosen and choreographed.

In fact, relative to this last comment, if you watch some of the videos posted by some of the “(p)atriots” from the Halls of Congress—and later that day—on YouTube, you can hear how unapologetically extreme and zealous they are, and how they own and are proud of their behavior.

Applying this to Education, Our Classrooms, and Our Students

All of this aside, as a school psychologist, I am also concerned about how our children and adolescents are processing this week’s events, and what lessons they are taking away.

This is a necessary, teachable moment that cannot be ignored.

To this end, I am indebted to my colleagues across the country who are expert in these educational areas, and who have provided the resources below to help teachers and other educators explain the events of this past week to students at different age levels (National Center for School Mental Health, K-12 Dive).

Child TrendsHelping Kids Understand the Riots at the Capitol |

National Education Association (NEA)Talking to Kids About the Attack on the Capitol |

The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP)Talking to Children About ViolenceManaging Strong Emotional Reactions to Traumatic Events:Tips for Families and TeachersSupporting Vulnerable Students in Stressful Times: Tips for Parents |

Common Sense MediaHow to Talk to Kids About Violence, Crime, and War |

National Public Radio (NPR)How to Talk to Kids About the Riots at the Capitol |

PBS News Hour ExtraClassroom Resource: Three Ways to Teach the Insurrection at the US Capitol |

Facing History and OurselvesResponding to the Insurrection at the Capitol |

_ _ _ _ _

In the end, all of us—when we are personally ready—need to decide what lessons we should learn from the events of the past week, the past two months since Election Day, and the past four or five (or more) politically and socio-culturally (for our country) challenging years.

Some people say, “This is not who we are.”

At this point, the far more important question is, “Who do we want to be?” . . . and . . . “How do we get there—personally, and in our neighborhoods, schools, communities, states, and across our currently challenged country?”

Best,