Sustaining Student Outcomes Beyond the Pandemic: Where Districts Need to Allocate Their American Rescue Plan (2021) Funds

Lessons Learned from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009)

[Originally Published on May 22, 2021; Updated on May 29, 2021]

Dear Colleagues,

Preface and Context

The U.S. Congress has passed three stimulus bills that have provided nearly $190.5 billion to the Elementary and Secondary Emergency Education Relief (ESSER) Fund administered by the U.S. Department of Education (USDoE). Each states’ funding is based on the same proportion share that they receive under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Title-I, Part A.

The three stimulus bills are:

- The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER I) Fund under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in March 2020.

- The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER II) Fund, passed in December 2020, the under the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act.

- The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER III) Fund was passed in March 2021, under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act of 2021.

The primary focus of ESSER I was to prevent, prepare for, and respond to COVID-19.

ESSER II and ESSER III funds will predominantly help school districts to reopen and operate safely, and to address the impact of the Pandemic on students. ESSER I funds are available for obligation through September 30, 2021. ESSER II funds are available through September 30, 2022. And, ESSER III funds are available through September 30, 2023.

While ESSER I and II funds relate to activities that address learning loss, at least 20% of a district’s ESSER III must address learning loss through the implementation of evidence-based interventions. Districts must ensure that the interventions respond to the students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral needs. In addition, the interventions must address the impact of COVID-19 on under-represented student subgroups such as, students of color, from low-income families, with disabilities, and who are English second-language learners, from migrant families, homeless, or in foster care.

This Blog focuses on ESSER III and ESSER II funding and where districts and schools can invest these funds to maximize students' academic and social, emotional, and behavioral recovery and long-term outcomes.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Introduction: American Rescue Plan Money is Coming!

On May 11, 2021, the U.S. Department of Education (USDoE) announced that more than $36 billion in grants under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act were awarded to over 5,000 institutions of higher education across our nation.

For (pre-)K to 12 districts and other Local Education Agencies (LEAs), this means that ARP funds will also soon be available for you. Indeed, most state departments of education have already applied for these funds and, once approved, it is expected that individual LEAs will need to apply in turn to receive their funds.

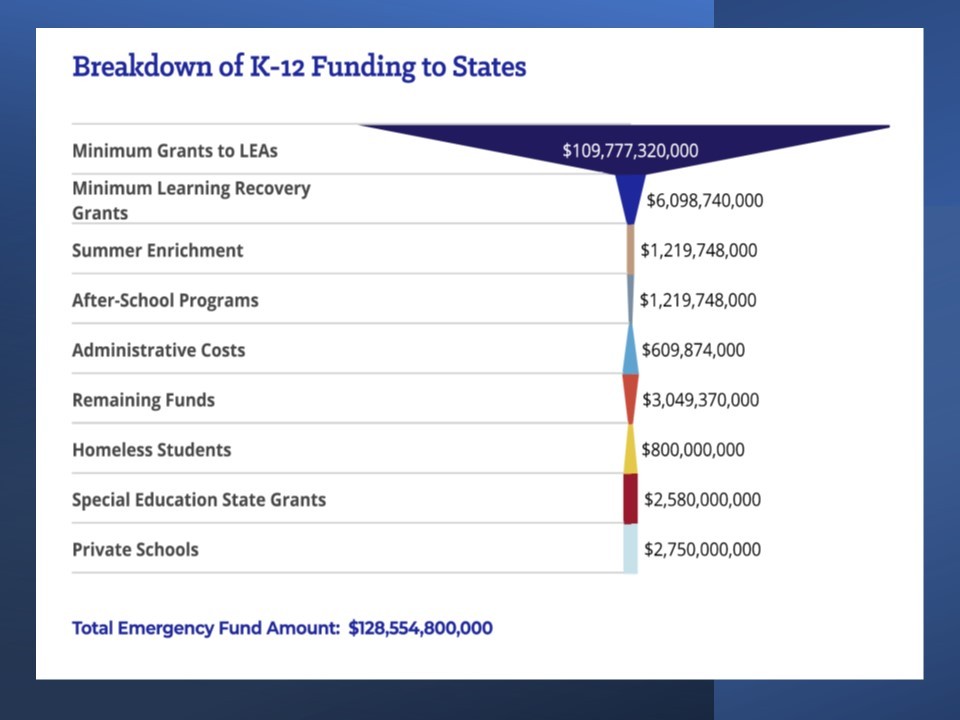

More specifically, the ARP is making approximately $129 billion in federal funds available for K-12 education through its Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) Fund. While most of this money will go to (pre-)K to 12 districts and LEAs, the states must use a portion of these funds to address the recovery and other service delivery needs of homeless students.

As passed by Congress, ARP funds have been allocated as follows:

Source: Education Week and the Learning Policy Institute

With the end of the school year coming soon, and little time between now and the beginning of the new school year, districts will have precious little opportunity to strategically plan for and develop sound proposals for these ARP funds.

This is similar to the Spring of 2009, when the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided billions to districts across the country in response to the Great Recession and the earlier melt-down of a number of key financial institutions.

Given the anticipated time crunch, and the ultimate educational goal of facilitating the sustained academic and social, emotional, and behavioral progress of all students, it is important to re-visit how districts used their ARRA funds, and how their investments directly impacted student outcomes. Using these “lessons learned,” districts can hopefully increase the return-on-investment relative to their incoming ARP funds.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Lessons Learned from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA; 2009) initially provided approximately $93.5 billion to (pre-)K to 12 education. The largest funding areas were:

- $53.6 billion for school districts and states to pay for teacher salaries and educational programs

- $21 billion for school facility modernization and construction

- $5 billion for Head Start

- $12 billion for special education programs, including job training for those with disabilities

An April 16, 2015 Report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that most of the ARRA funds distributed to districts were spent on “capital outlays, such as construction, land purchases and equipment acquisition.”

Even when districts used the funds to hire personnel, the Report noted that this came largely in the form of non-teaching staff. The stated reason for this was that districts “may have been less willing to hire new staff for risk that, once the short-lived grants were spent, the new staff would need to be let go.”

In the end, a January 5, 2012 Congressional Budget Office analysis reported that, of the estimated $93.5 billion in ARRA funds available to the USDoE for distribution, fully $6.3 billion was not spent. This was the second largest amount of unspent ARRA funds among the sixteen-plus federal agencies tracked.

Even in the face of these unspent ARRA funds, a significant amount of money was used in ways that had no direct effect on students.

At the extreme level, the Wisconsin-based MacIver Institute reported (February 24, 2010) that the New Holstein School District legally paid $416,219 in ARRA funds to their health insurance trust and an additional $237,862 to its utility companies.

The Institute explained these expenditures by citing the mixed messages coming from the U.S. Department of Education.

On one hand, the USDoE published a general guidance reminding districts that ARRA money should “supplement, not supplant” funding for educational expenses. On the other hand, the USDoE told ARRA awardees that, “The ARRA is expected to be a one-time infusion of substantial new resources. These funds should be invested in ways that do not result in unsustainable continuing commitments after the funding expires. . .Invest the one-time ARRA funds thoughtfully to minimize a ‘funding cliff.’”

On the whole, the ARRA expenditures and experiences detailed above suggest that ARRA funds were largely spent on things that had only indirect effects on students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral instruction, progress, and outcomes. This is consistent with my experiences during ARRA as I worked as a Federal Grant Director at the Arkansas Department of Education and across the country as a consultant.

Specifically, I saw well over a thousand school districts spend their ARRA funds on equipment (e.g., buses and whiteboards), quickly outdated computers and software, off-the-shelf supplemental curricula, and other disposable materials. Moreover, I witnessed numerous indiscriminate “shop ‘til you drop” spending sprees where districts bought unvetted “stuff,” because their “use it or lose it” ARRA funds were about to be recalled.

And so, in the context of the forthcoming ARP funds, the critical question is:

Did sustained outcomes, relative to students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral progress, result from the ARRA money distributed to districts across the country?

Upon reviewing the annual Elementary and Secondary Education Act and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act outcomes reported to the USDoE during and immediately after the ARRA funding, the clear answer to this question is, “No.”

So, based on the funding lessons learned from ARRA, how can districts target their ARP funds more judiciously toward the strategic needs of their students, and toward meaningful and sustained academic and social, emotional, and behavioral student outcomes?

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

What Practices Should Districts Target with their ARP Dollars?

Given the ARRA discussion above, it would be much easier to talk about what districts should not target in the ARP proposals that they submit to their respective state departments of education. But I am going to largely avoid that trap.

Indeed, for those who regularly read my Blog articles, you know that I am going to emphasize the importance of strategically targeting research-based practices, rather than embracing generic frameworks, programs, and computer-based instructional or intervention software systems that do not involve direct teacher or related service staff support.

But in emphasizing research-based practices, I do not recommend using a top-down approach that involves, for example, consulting the most-recent Hattie list of the strategies that correlate most strongly with student achievement.

CLICK HERE for the April 13, 2019 Blog Article:

“How Hattie’s Research Helps (and Doesn’t’ Help) Improve Student Achievement. Hattie Discusses What to Consider, Not How to Implement It (More Criticisms, Critiques, and Contexts)”

_ _ _ _ _

Instead, I strongly advocate for a bottom-up approach where districts and schools analyze the current academic and social, emotional, and behavioral status, progress, strengths, and needs of their own students, and then strategically determine (a) what differentiated instruction and student grouping approaches will maximize learning; and (b) what additional multi-tiered services, supports, and interventions will most impact students who are academically struggling and/or exhibiting social, emotional, or behavioral challenges.

CLICK HERE for the March 6, 2021 Blog Article:

“A Pandemic Playbook to Organize Your School’s Academic and Social-Emotional Strategies Now and for the 2020-2021 School Year: Where We’ve Been and What You Should Do”

In this context, students who are at-risk, underachieving, unmotivated, unresponsive, and unsuccessful should be particularly supported. And this should especially include students from poverty, with disabilities, who do not have English as their primary language. . . and students of color who have experienced implicit and explicit bias, school finance gaps, and institutional inequities for many past generations.

Once this bottom-up strategic planning is complete, the ten practice and support areas below are recommended to produce meaningful and sustained (i.e., beyond ARP) academic and social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for the students especially identified above.

Note that some of these ideas require coordination and collaboration with other partners. In addition, a few of the ideas may need approvals from your respective departments of education (or beyond).

_ _ _ _ _

Ten Recommended Practice and Support Areas for your ARP Funds

Recommendation 1: Grow Your Own Specialists—For Existing Staff.

Even before the Pandemic, many states had shortages in the following areas: Administrators, Special Education Teachers, Counselors, School Psychologists, General Education Teachers in STEM. Because of the Pandemic, the aging-out of educators, and the lower numbers of new educators in the university/alternative certification pipeline, these pre-existing shortages may increase.

One resolution is for districts to recruit willing employees (including paraprofessionals and similar support staff), pay for the training and release time they need to be credentialed in one or more of the shortage areas, and offer additional salary incentives in return for their written commitment to remain in the district for a specified period of time.

ARP money could go for on-site or virtual university or post-graduate training, or for “Grow Your Own” PLCs, Leadership Institutes, or Collegial Cadres. Districts could collaborate with local, virtual, or Week-end Program institutions. And nearby districts could collaborate by sponsoring different specialization cohorts (e.g., District A = Administrators; District B = Special Educators, etc.), and “enrolling” staff across the participating districts.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 2: Grow Your Own Teachers and Specialists—For High School Graduates and Community Applicants.

Another variation of Recommendation #1 involves recruiting high school students and interested and/or “second-career” community members into university or alternative certification teacher or shortage-area training programs.

This would, once again, involve using ARP funds to pay for the necessary training, release time (as relevant), materials, and support groups. For the matriculating high school graduates, districts should explore using ARP money to fund full scholarships or 529 College Savings Plans so that the one-year ARP funds can be used across multiple years.

If, as described earlier in this piece, districts were able to use 2009 ARRA funds to pay for health insurance and utility bills, why not explore a 529 Savings plan option—using, for example, a district’s educational foundation to oversee the funds. . . along with a corporate matching program to add to the fund?

It never hurts to ask.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 3: Grow Your Own Coaches and Intervention Specialists.

To Recommendations #1 and #2 above, let’s add the recognition that districts need more and better trained educators in a whole host of instructional and intervention “niche” areas: for example, the science of literacy, classroom management (especially, to address disproportionality), instructional modifications and accommodations, assistive and technology-based supports, virtual instruction and computer applications, social-emotional interventions for challenging students, cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Here, the ARP funds can fund the professional development for interested or designated employees and pay for the release (or supplemental work/comp) time and materials needed. Once again, the “quid pro quo” would be an assurance that participants must stay in the district for a specific period of time after the training (so they don’t, for example, leave for another district’s higher paying position or become an independent consultant with their new skills).

Another expectation might be that these professionals become collegial or supervisory coaches in their niche area, or intervention specialists for students with challenging, multi-tiered needs.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 4: Full-Service School Programming and/or Staffing.

The benefits of Full-Service School Programs—whether they include on-site, mobile, on-call, or virtual staffing elements—have long been known.

With (or without) the Pandemic, many students have not received the medical, dental, hearing, eye-care, emotional, mental health, or other supports that they need. And these services and supports could be provided—at least for one year—through ARP funds, or to establish the infrastructure of a long-term program.

For example, ARP funds might be used to build an actual full-service school space.

And they certainly could be used to fund the (on-site or virtual) school nurses, mental health professionals, attending dentists and physicians, and other supports needed (e.g., glasses, speech, PT and OT, nutritionists, and other specialists or specialist appointments) whether or not the students qualify for Medicaid or because of a disability.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 5: Academic Tutors and Credit Recovery Instructors.

Before he passed away last month, Johns Hopkins University Professor Robert Slavin strongly advocated for a national post-Pandemic program of academic tutoring options across our country. This is an important potential use of ARP funds.

And the tutors can come from multiple sources.

For example. . . tutors could be retired teachers or experts, after-school tutoring or college prep businesses, parents or others in the community, college work-study students, high school graduates who are delaying their matriculation to college, or even high school students who are paid to work with middle or elementary students.

The tutoring could be live or virtual, during or after school, or during the summer or on weekends.

Finally in this area, ARP funds could be spent on Credit Recovery Instructors so that students can receive the live instruction that they need. This would directly address a common problem in computer-based Credit Recovery Programs where students earn the credits, but do not learn and master the material at a functional level.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 6: Social-Emotional Support Mentors or Case Managers.

Instead of being Academic Tutors and Credit Recovery Instructors, some of the individuals listed in Recommendation #5 could become Social-Emotional Support Mentors or Case Managers.

As more school and community assessments and data emerge, it is apparent that there are many students who need social and emotional supports—whether due to pandemic-specific or pre-pandemic circumstances. While some of these students need relationships with related services or mental health professionals, others just need a relationship with a caring person.

And this could be a target for some ARP funds. . . to employ, for one year, a cadre of before, during, after-school, or week-end mentors to help support at-risk or emotionally-needy students.

Beyond the mentoring, ARP funds also could be used to employ Social-Emotional Support Case Managers—bachelor’s-level individuals to bridge the gaps, and help coordinate and integrate the school, home, community, and agency-based services being delivered to some students. Many social service or private mental health agencies employ Case Managers exactly for these purposes.

Why shouldn’t a school district either do the same or contract for these services from the community?

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 7: Data-, Tech-, or Case-Managers.

As districts acquire more sophisticated Student Information or Data Management Systems, and states roll-out more comprehensive school and schooling data-dashboards, the availability of data has exponentially exploded. And yet, the people, processes, and expertise to track, analyze, interpret, and report these data at the local level have not kept pace.

This has simultaneously resulted in information overload and result shortfalls.

Similarly, as more students experience academic and/or social, emotional, or behavioral challenges, many of them will need to be discussed and served by the school Multi-Tiered Services or Intervention Teams. At this cumulative and multi-disciplinary level, the importance of collecting, analyzing, and reporting each student’s longitudinal educational and social history—from preschool through their current grade placement—is essential to understand how long the current problems have existed, their underlying root causes, and the past interventions that have succeeded or not.

Once again, some schools do not have the personnel with the time, responsibility, and expertise to synthesize and present this information in a cogent way at the beginning of the Team’s discussion. . . so that they best consultants and the right intervention targets are selected.

Given these situations, ARP money could be used to employ Data- or Tech-Managers who could help districts to track, analyze, interpret, and report—formatively and summatively—on their student, staff, schools, and state dashboard data. The formative information could help districts to make effective and efficient curriculum, instruction, intervention, and programming decisions. The summative information could help prepare state and federal accountability reports and track the return-on-investment of ARP-funded initiatives.

The ARP money also could employ Student Case Managers to collect, analyze, and report on longitudinal educational and social history of students being presented to the Multi-Tiered Services or Intervention Team. As services, supports, or interventions are implemented for these students, the Case Managers could also track the data-based results to determine their success, need for modification, or need to review the case at the Team level.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 8: Establish a Career and Technical Education Center, Internship, or “5th Year” Apprenticeship Program.

While recognizing its relevance and importance, many districts have not had the start-up funds to establish “21st Century” Career and Technical Education (CTE) Centers, Internships, or “5th-Year” Apprenticeship Programs in one or more specialization areas (e.g., computers and cybersecurity, medical and health services, plumbing or electricity, food services and hotel management, etc.).

Recognizing that not all graduates will go to college, districts—perhaps in partnership with businesses in the community and/or their local Community College—can use ARP funds to buy or build their CTE space, outfit or acquire their CTE equipment, and/or pay the staff or students for their participation in CTE high school classes, high school internships, or 5th-Year apprenticeships. All of these investments will lead to real-world skills, post-graduation employment, and well-paying, long-term jobs.

In addition, these CTE programs could—educationally and financially—help students who are potential drop-outs to stay in school, give students with disabilities post-graduation employment skills and options, and create much-needed pipelines for businesses that struggle to find and retain well-skilled and highly productive employees.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 9: Parent Liaisons and Parent Educators

Two major issues resulting from the Pandemic have been attendance, and parents choosing to keep their children home from school and/or on virtual instruction.

Related issues have been students (a) not showing up (at all, or with their computer cameras off) for virtual instruction; (b) not learning and mastering crucial academic skills; (c) becoming isolated, losing interpersonal and other social skills, and experiencing emotional or mental health issues that are unidentified or monitored; (d) not taking this year’s state proficiency tests (where given); (e) dropping out of school and moving to full on-line instruction—with a concomitant loss of per pupil expenditures for their districts; and (f) disappearing entirely.

Difficulties communicating with parents, and helping them to understand the importance of vaccinations, on-site education, and their children’s academic and social, emotional, and behavioral status, progress, and needs have simultaneously occurred.

To address these issues and needs, and to help re-establish positive and collaborative relationships with (especially isolated, disaffected, or untrusting) parents and others in the community, ARP money could be used to hire Parent Liaisons and Parent Educators from the community.

Ideally, these would be actual parents who are trained and supervised by the district. These Parent Liaisons and Parent Educators would reflect the diverse demographics and viewpoints of the community at-large and would benefit themselves from employment and giving back to their communities.

But more important, these Parent Liaisons and Parent Educators would be strategically selected so that other parents will identify with and trust them—increasing the probability that they will listen to and embrace their messages.

_ _ _ _ _

Recommendation 10: College Entrance and Dual-Enrollment Support Mentors

Some critical outcomes from the Pandemic have been high school students (a) getting off-track relative to qualifying for the best college program possible; (b) not applying for college or post-graduation training; (c) not applying for financial aid and available scholarships; (d) not taking dual-enrollment courses; (e) delaying college matriculation; and (f) being accepted into college, but not showing up.

Here, ARP funds could be used to employ College Entrance and Dual-Enrollment Mentors who would carry a case load of students, provide them personal support, and improve the outcomes above. As in some of the recommendations above, these Mentors could be community college or four-year university students, retired teachers or others from the business community, professionals who have college counseling or advisement businesses, or other relevant individuals.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

The focus of today’s Blog has been on how to apply for and invest your short-term American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds in ten key effective practice growth areas so that your district or school (a) can address specific students’ current academic and social, emotional, and behavioral needs, while (b) compounding the results of those investments into long-term, sustained outcomes in these same areas for all students.

We addressed the importance of immediately addressing the needs of students who are at-risk, underachieving, unmotivated, unresponsive, and unsuccessful. And we included in this group students from poverty, with disabilities, who do not have English as their primary language. . . and students of color who have experienced implicit and explicit bias, school finance gaps, and institutional inequities for many past generations.

In the first part of this Blog, we identified the financial “pots” that are available for (pre)K to 12 districts or LEAs according to the ARP legislation.

We then provided an historical contrast with the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), providing documentation the billions of ARRA dollars awarded to districts across the country were invested in (a) capital outlays, such as construction, land purchases and equipment acquisition; (b) non-teaching (rather than instructional) staff; and (c) other materials and resources that were not vetted (because districts were spending the money before losing it at the end of the award period), and that did not have direct impact on student outcomes.

We also documented how many U.S. Department of Education ARRA dollars were “left on the table,” and how districts were given precious little time to strategically plan for and allocate their money.

With these ARRA “lessons learned” in-hand, we recommended ten growth areas to districts to consider with their ARP money. If all of the financial metaphors are hitting home, then you are fully understanding these recommendations.

Once again, the focus here is on addressing short-term needs while building a long-term infrastructure (using some of the money as a “start-up”) to directly address students’ academic and social, emotional, and behavioral needs.

The additional focus is on well-researched and proven practices, and not global frameworks, untested programs, and off-the-shelf curricula or computer-based interventions.

The Ten Investment Recommendations were:

- Recommendation 1: Grow Your Own Specialists—For Existing Staff.

- Recommendation 2: Grow Your Own Teachers and Specialists—For High School Graduates and Community Applicants.

- Recommendation 3: Grow Your Own Coaches and Intervention Specialists.

- Recommendation 4: Full-Service School Programming and/or Staffing.

- Recommendation 5: Academic Tutors and Credit Recovery Instructors.

- Recommendation 6: Social-Emotional Support Mentors or Case Managers.

- Recommendation 7: Data-, Tech-, or Case-Managers.

- Recommendation 8: Establish a Career and Technical Education Center, Internship, or “5th Year” Apprenticeship Program.

- Recommendation 9: Parent Liaisons and Parent Educators

- Recommendation 10: College Entrance and Dual-Enrollment Support Mentors

_ _ _ _ _

As a bonus, we also want to call your attention to a recently published resource (May, 2021) focusing on teacher recruitment and retention, targeting the diversification of the workforce, and emphasizing the positive impacts on students.

The resource, Teaching Profession Playbook, was developed by 26 organizations including the Council of Chief State School Officers, the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Parent Teacher Association. It describes important strategies and provides examples for attracting and supporting a wide range of different teachers and other educators.

[CLICK HERE for this Resource]

_ _ _ _ _

May 29, 2021 Update:

We also want to call your attention to a Fact Sheet released by the USDoE on May 26, 2021 that describes how districts can use their ARP, ESSER I and II, and Governor's Emergency Education Relief (GEER) I and II funds.

[ESSER Fact Sheet US DoE May 26 2021.pdf]

Among the acceptable uses, districts can use the money to:

- Invest in services and supports—including those that enhance digital equity—to address the instructional time lost by students due to COVID-19;

- Pay for COVID-19 vaccinations, vaccination clinics, and testing; personal protective equipment, hand sanitizer, and masks; and outreach efforts—for example—that publicize the importance of getting vaccinated and provide incentives like paid leave time to get them;

- Prevent layoffs, or provide reasonable “premium pay” (including bonuses) to educators, for example, to ensure the availability of teachers during the summer;

- Renovate or remodel schools to address COVID-19-related needs like improved air quality, heating, and ventilation; and

- Provide job training, postsecondary counseling, and other services to help this and last year’s graduating students—including those with disabilities who can be served until age 21—to transition into careers or college.

This Fact Sheet says that (a) ESSER I funds do not need to be obligated before ESSER II or ARP funds; (b) ESSER and GEER funds do not have supplement or supplant requirements—and that states cannot use these awards—without a USDoE waiver—to substantially reduce their existing K-12 commitments; (c) ARP funds cannot be used by districts to disproportionately reduce the combined state and local funding to high-poverty schools; and (d) state lawmakers cannot limit districts’ use of the largest funding areas in ESSER and GEER, but that state education departments can put limits on these funds’ use for administration.

Finally, relative to the “premium pay” allowance (such as teacher bonuses), the USDoE guidance says that such funds must be used “pursuant to an established plan” that is “consistent with applicable collective bargaining agreements.”

_ _ _ _ _

The USDoE’s Fact Sheet brings us back to the primary thesis in this Blog.

Clearly, the ESSER (and GEER) funds available to districts have a broad range of potential uses. We have argued for districts to consider using these funds to directly impact students’ current and long-term outcomes.

While we understand that some districts may use these funds for heating, cooling, and ventilation upgrades in their schools, we hope that such capital outlays will free up other budgeted funds and be reallocated to some of the Recommendations detailed earlier in this Blog.

If funds are used to purchase computers to close the digital equity gap, we hope that additional funds are allocated for the personnel needed to teach, support, and instructionally guide our students so that these resources actually result in enhanced student learning, skills, and mastery.

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that the ARP, ESSER, and ARRA discussion and documents, and the funding recommendations above are useful to you and your staff. We have a critical opportunity, with funding, to address a number of the academic and social-emotional effects of the Pandemic. And we want to maximize this opportunity with investments that have immediate and long-term benefits.

If there is anything that I can do to add value to the discussion above in your setting, please feel free to contact me with your questions.

As always, I am happy to provide a free, one-hour consultation or “chat session” on how to apply these (and other) ideas to best meet the needs of your students, staff, schools, and system.

Best,