The Components Needed to Eliminate Disproportionate School Discipline Referrals and Suspensions for Students of Color Do Not Require Anti-Bias Training:

Behind Every Iron Chef is an Iron-Clad Recipe (Part II)

Dear Colleagues,

I tell a student that the most important class you can take is technique. A great chef is first a great technician. 'If you are a jeweler, or a surgeon or a cook, you have to know the trade in your hand. You have to learn the process. You learn it through endless repetition until it belongs to you. Jacques Pepin

Introduction

Cloaked in subdued anxiety, I am actually writing this from an airplane—my first business trip (to California and New Mexico) in eighteen months.

Leaving behind the virtual world (for now), I am looking forward to helping four schools prepare—not just for the troubling effects of the pandemic on their students’ social, emotional, and behavioral health—but for the issues that also were present before COVID-19.

One of these pre-pandemic issues involves helping teachers, staff, and administrators to better understand the behavior of students of color. Too often, when these students demonstrate “inappropriate” behavior, they are viewed as “discipline problems.”

When educators understand the historical, cultural, sociological, and psycho-educational “make-up” of students of color, they more accurately contextualize and respond to their “inappropriate” behavior.

[Please note the quotation marks above.]

One of the challenges here is getting teachers and administrators to see their place in the decades-old national problem where students of color are disproportionately sent to the principal’s office for “discipline,” and then disproportionately suspended or placed in alternative programs by their administrators.

This problem often includes teacher referrals and administrative placements for behaviors that are dealt with in the classroom for White students, but responded to more punitively for students of color.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

An Overview of Part I in this Series

This two-part Blog Series is dedicated to helping districts and schools to successfully eliminate disproportionate discipline referrals and (punitive) actions for students of color.

In Part I of the Series, we presented a definition of “racism,” and talked about Critical Race Theory. We did this to emphasize that (a) the disproportionate disciplinary treatment of students of color—especially Black students (as well as students with disabilities)—has existed for decades, and that (b) initiatives to eliminate disproportionality should not be linked to the recent politicized conversation involving Critical Race Theory.

Relative to the latter area, we objectively reviewed the current information regarding Critical Race Theory and its presence in America’s classrooms. We also expressed concerns about the impact that legislative and other policy-level actions—focused on restricting or eliminating the discussion of Critical Race Theory in schools—might have on teachers and students.

In the end, with citations, we documented:

- The political nature of the Critical Race Theory legislation in a number of states;

- The fact that most teachers are not teaching this theory in their classrooms;

- Concerns that schools are going to be wasting a lot of time this year on Critical Race Theory discussion, debate, professional development, lesson plan analysis, and administrative supervision (to ensure that teachers understand and do not include Critical Race Theory in their classrooms)—because of the legislation and/or because of misinformation in many communities; and we documented

- The additional implications relative to teacher trust, academic freedom, and the potential that legitimate classroom instruction and discussion on race, racism, equity, and Black history will be reduced, sanitized, or eliminated because teachers are afraid either to be unjustly accused of teaching Critical Race Theory, or to trigger undue student controversy or emotions.

Based on the information presented in Part I, we recommended that educators avoid wasting their time by looking past the Critical Race Theory politics and debate and, instead, focus directly on how to eliminate the disproportionate disciplinary referrals and actions against students of color—a long-standing result of racial bias in our schools.

Part I then discussed the different approaches that have been implemented in the past to address school-level disciplinary disproportionality—explaining why they have not worked and, hence, why they should be avoided in the future.

This presentation was organized by describing six Reasons or Flaws:

- Reason/Flaw #1. Educational leaders have tried to change the disproportionate numbers through policy and not practice.

- Reason/Flaw #2. State Departments of Education (and other educational leaders) have promoted whole-school programs that are unproven or have critical scientific flaws.

- Reason/Flaw #3. Districts and schools have implemented frameworks that target conceptual constructs, rather than instruction that teaches social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

- Reason/Flaw #4. Districts and schools have not recognized that classroom management and teacher training, supervision, and evaluation are keys to decreasing disproportionality; and they are depending on Teacher Training Programs to equip their teachers with effective classroom management skills.

- Reason/Flaw #5. Schools and staff have tried to motivate students to change their behavior when they have not learned, mastered, or are unable to apply the social, emotional, and behavioral skills needed to succeed.

- Reason/Flaw #6. Districts, schools, and staff do not have the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement the multi-tiered (prevention, strategic intervention, intensive need/crisis management) social, emotional, and/or behavioral services, supports, and interventions needed by some students.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

An Overview of Part II in this Series

In this Series Part II, we respond to the six reasons/flaws above by providing effective practices and solutions to decrease or eliminate disproportionality.

As part of this discussion, we directly address an embedded issue in many of the race-based laws passed by different states during this year’s legislative sessions.

In a July 14, 2021 Education Week article, “Four Things Schools Won’t Be Able to Do Under ‘Critical Race Theory’ Laws,” it was noted:

In recent years, some school districts with shifting racial demographics have launched multi-pronged efforts to better serve students of color. They’ve formed diversity, inclusion and equity committees made up of students, teachers, and administrators, hired equity officers, and offered ongoing training for teachers to recognize and rid themselves of their unconscious biases, which many experts argue lead to, among other things, disproportionate suspensions and expulsions, for Black and Latino students.

Now, in at least nine states (e.g., Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa), those efforts, advocates and district administrators say, would effectively come to a halt.

We clearly believe that staff who are specifically motivated by explicit bias and overt prejudice should be held directly accountable for discriminatory behavior. This has not changed due to the recent state legislation.

However, we also recognize that—even if it were permitted—“ongoing training for teachers to recognize and rid themselves of their unconscious biases” has largely not worked.

[See our December 5, 2020 Blog:

“Training Racial Bias Out of Teachers: Who Ever Said that We Could? Will the Fact that In-Service Programs Cannot Eliminate Implicit Bias Create a Bias Toward Inaction?”

So, at least on this level, the recent state legislation in this area should not dramatically impact school and districts’ effective efforts to decrease and eliminate disciplinary disproportionality.

And yet, this still is not occurring in so many districts and schools because, as discussed in Part I of this Blog Series, many have focused their efforts in one or more of the six Reason or Flaw areas above. . . and many are not using the scientific, psychoeducational components that do not involve racial anti-bias training, and that do involve essential and proven field-tested practices.

Thus, in this Blog, we will:

- Describe five interdependent psychoeducational components and their specific, embedded practices (addressing Flaw #1); that are

- Organized within a strategically-implemented, evidence-based, multi-tiered professional development and coaching-centered whole-school initiative (addressing Flaw #2); that focuses on

- Teaching students—from preschool through high school—specific, observable, and measurable social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills (addressing Flaws #3 and 5).

- We will then advocate the use of a data-based problem-solving process—when students demonstrate frequent, persistent, unresponsive, significant, or extreme levels of inappropriate, disruptive, unpredictable, antisocial, or dangerous behavior—to objectively identify the root causes of the behavior, and to discriminate discipline problems from social, emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health problems. . . so that

- The assessment results can be linked to the strategic or intensive multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, or interventions that will eliminate the student problem and replace it—once again—with appropriate behavior (addressing Flaw #6).

While this Blog will primarily focus on student outcomes, note that we provided an extensive discussion in Part I of this Series addressing the fact that some teachers, staff, and administrators are complicit in the disproportionate office referral and school suspension numbers when they (re)act due to a lack of (student and racial) knowledge and information, understanding and analysis, skill and application, motivation and self-reflection, entitlement and privilege, or prejudice and bias.

To address these professional (or unprofessional in the case of prejudice and bias) gaps, we recommended district- and school-level training, coaching, supervision, and evaluation as keys to decreasing disproportionality (addressing Flaw #5).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Solving the Disproportionality Dilemma

This Blog began with a quote from a Master Chef discussing the importance of (over-)learning the techniques needed to prepare a world-class meal.

Expanding on this analogy by reflecting on the title of this Blog, good technique—which involves process, must be complemented by a good recipe—which involves substance (i.e., the ingredients) and sequence (i.e., the step-by-step implementation).

Applying this to eliminating disproportionality, schools need to have both a proven recipe for change, and the complementary processes needed to prepare the recipe with intent and fidelity.

A major principle grounding the disproportionality recipe is:

- When all students (including students of color) are taught (in developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways—from preschool through high school), and when they have mastered and can apply specific and scaffolded interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills... and

- When they are prompted, motivated, and held accountable for using these skills in all school settings and circumstances. . .

- They will consistently demonstrate appropriate, prosocial interactions. . . such that

- The need to need a disciplinary referral to the principal’s office will become moot.

Critically, and as acknowledged earlier, some students will need multi-tiered strategic or intensive services, supports, strategies, or interventions in order to learn and demonstrate their social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

To determine these services and supports, data-based analyses should be conducted to determine why the students are not learning or performing so that, like a Master Chef, modifications to the recipe can occur—still resulting in a world-class meal.

_ _ _ _ _

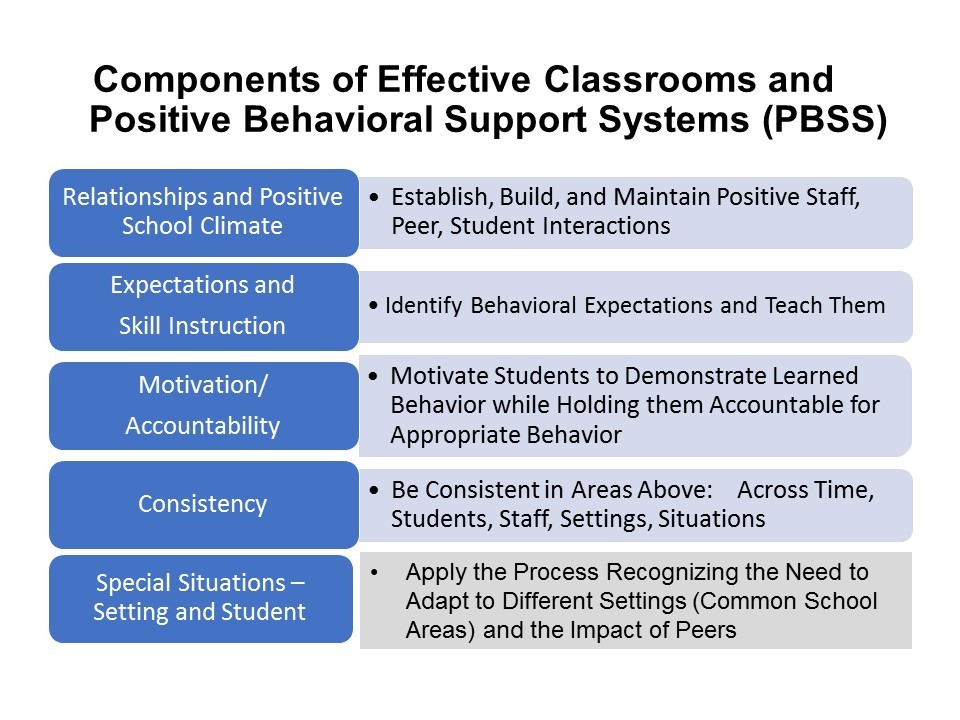

At the center of the disproportionality recipe are five interdependent components that have an assortment of important practices within them (see the Figure below; from: Knoff, H.M. (2014). School Discipline, Classroom Management, and Student Self-Management: A Positive Behavioral Support Implementation Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press; CLICK HERE for more information).

These components are:

These components are:

- Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climates

- Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skill Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Consistency and Fidelity

- Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

They are briefly described below.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climate

Effective schools work consciously, planfully, and on an on-going basis to develop, reinforce, and sustain positive and productive relationships so that their cross-school and in-classroom climates mirror these relationships.

Critically, however, these relationships include the following interactions: Students to Students, Students to Staff, Staff to Staff, Students to Parents, and Staff to Parents.

Relative to minority students, these interactions involve understanding them, their backgrounds, their personal and familial histories, their strengths and weaknesses, and their personal or unique stories or experiences.

For minority students, this also includes understanding their racial and cultural backgrounds, but care is needed not to stereotype these backgrounds such that individual students are not seen as individuals.

Positive relationships and school/classroom climates result when all of the adults in a school actively participate. But the students are also part of this process, as well as the different formal and informal peer groups, clubs, and organizations represented across the school.

_ _ _ _ _

Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction

All students from preschool through high school—including students of color—need to be explicitly taught (just like an academic skill) the explicit social, emotional, and behavioral expectations in their classrooms and across the common areas of the school. These expectations need to be communicated in a positive, prosocial—rather than a negative, deficit-oriented—way. That is, students need to be taught “what to do,” rather than “what not to do.”

Indeed, teachers and administrators will have more behavioral success teaching and prompting students, for example, to (a) walk down the hallway (rather than “Do not run”); (b) raise your hand and wait to be called on (rather than “Do not blurt out answers”); or (c) accept a consequence (rather than “Don’t roll your eyes and give me attitude”).

In addition, these expectations need to be behaviorally specific—that is, we need to describe exactly what specific, observable steps we want students to perform—for example:

- Walk onto the bus quietly, using social distancing;

- Sit in the first open seat and move all the way in;

- Put your books on your lap or your bookbag under the seat in front of you;

- Talk only with your neighbors using a whisper or conversational voice; and

- Stay seated until the bus has stopped, and it is your turn to leave.

Indeed, it is not instructionally helpful to talk in constructs—telling students that they need to be “Respectful, Responsible, Polite, Safe, and Trustworthy.” This is because each of these constructs involve a wide range of undefined behaviors. Moreover, at the elementary school level, students really do not functionally or behaviorally understand these higher-ordered constructs. At the secondary level, meanwhile, students often interpret these constructs (and their many inherent behaviors) very differently than staff.

Thus, and as above, we need to teach students the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills that we want them to demonstrate at each grade and developmental level.

Moreover, we need to teach these skills the same way that successful basketball coaches teach the plays in their playbooks. That is, we need to (a) teach students the specific steps for each social skill, along with the related behaviors; (b) positively demonstrate the steps to them in meaningful and real-life scenarios; (c) give students structured opportunities to practice each skill in simulated roleplays with guidance and explicit feedback; and then (d) help students to apply (or transfer) their new skills more automatically and independently to “real-world” situations.

Embedded in this instruction is the social problem-solving needed to select the best behavioral choices for different situations. Also included is how to maintain self-control when faced with emotional triggers and stress, peer pressure and conflict, or other home or school disruptions.

Significantly, there are hundreds of important social, emotional, and behavioral skills that could be taught during students’ school careers. Examples of some needed social skills include: Listening, Following Directions, Asking for Help, Ignoring Distractions, Dealing with Teasing and Bullying, How to Accept a Consequence, How to Deal with Losing or Not Getting Your Own Way, How to Handle Peer Pressure and Rejection, How to be a Good Leaders and a Good Team Member, How to Set Goals and Develop Good Action Plans.

All of the core social skill instruction is led by general education teachers. This is because (a) they know the students better than anyone else; (b) they have more opportunities to prompt, practice, reinforce, and correct the skills in real-life classroom situations; (c) they need to use these skills to facilitate classroom management and positive school climates; and (d) they need to integrate these skills into students’ academic engagement and success.

For students who need modified, small group, or individual (cognitive behavior therapy-based) instruction (e.g., at the Tier 2 or Tier 3 levels), this is done by school or school-based mental health staff—counselors, psychologists, or social workers.

Relative to disproportionality, when students of color learn these skills, routines, and interactions—in developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways, they will more consistently demonstrate appropriate, prosocial interactions, and there will be less (no) need for discipline.

_ _ _ _ _

Student Motivation and Accountability

For the skill instruction described above to “work,” minority students need to be motivated to and held accountable for demonstrating positive and effective social, emotional, and behavioral skills.

Scientifically, motivation is based on two component parts: Incentives and Consequences.

But to work, these incentives and consequences must be meaningful and powerfulto the students (not just to the adults in a school).

That is, too often schools create “motivational programs” for students that involve incentives and consequences that the students couldn’t care less about. Thus, the programs look good “on paper,” but they hold no weight in functional, behavioral reality—at least from the students’ perspectives.

But this is not about motivational programs, it is about effective practices.

And in order to decrease or eliminate disproportionality, while increasing effective classroom management and student self-management practices, teachers need a classroom discipline “road map.”

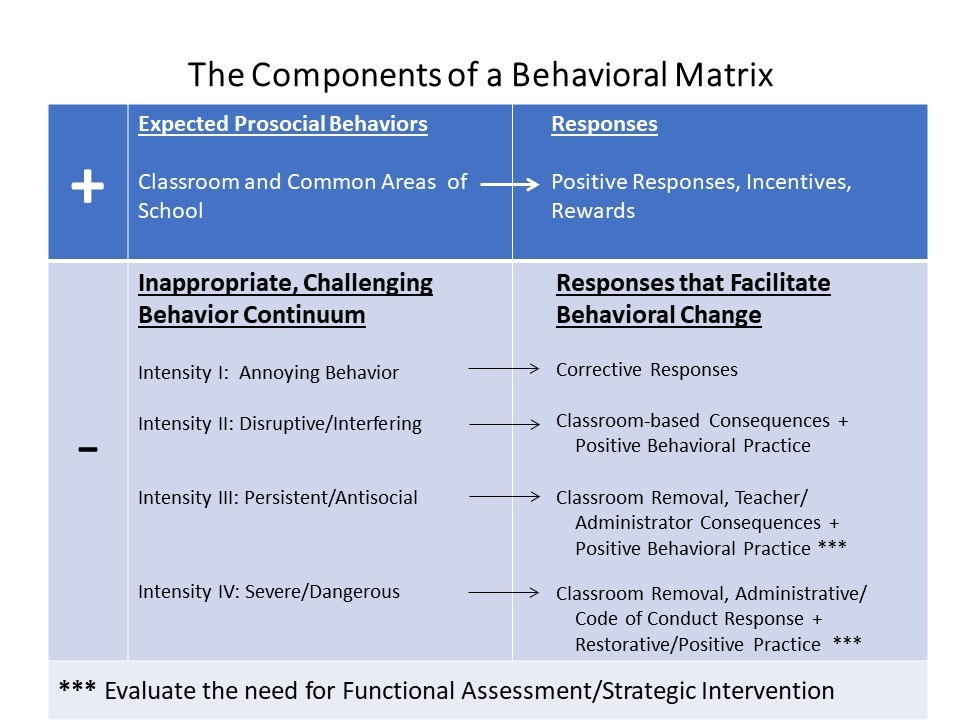

For us, we call this road map the Behavioral Matrix, and we work constantly with schools nationwide to help them develop their own grade-level Matrices that are sensitive to and reflective of their staff and students.

The Behavioral Matrix is the “anchor” to a school’s behavioral accountability and progressive school discipline system. At the Elementary School level, there typically is a Behavioral Matrix at each grade level because of the developmental differences across prekindergarten through (typically) Grade 5 students.

At the Secondary level, there typically is a school-wide (for example, Grade 6 to 8, and Grade 9 to 12) Matrix for each middle and high school, respectively. Significantly, at times these schools create separate Grade 6 and Grade 9 matrices, because these students are often entering their middle or high schools, respectively, for the first time, and the schools want to individualize the behavioral expectations and accountability attention specifically to them.

Every Behavioral Matrix has quadrants that address appropriate versus inappropriate behavior, respectively (see the Figure below). The first two quadrants of the Matrix specify (a) the behavioral expectations in the classroom connected (b) with positive responses, motivating incentives, and periodic rewards.

The third and fourth quadrants, respectively, identify four progressive “Intensity Levels” of inappropriate behavior, connected with research-based responses and strategies that facilitate a change of this inappropriate behavior.

When teachers and administrators use these quadrants with fidelity, they help to eliminate both disproportionate referrals of students of color to the principal’s office, and repeated school suspensions of the same students—especially, when multi-tiered services and supports are in order.

When students are taught, as recommended, about the different levels of inappropriate behavior and how each level will be addressed, many (a) are motivated to avoid these responses by demonstrating appropriate behavior, or (b) are not surprised by the teacher consequences or administrative responses that occur when they choose to demonstrate inappropriate behavior.

In addition, many students internalize the Matrix, and it becomes an internal, intrinsic self-management guide that facilitates self-control, behavioral decision making, self-reinforcement, and self-accountability.

When teachers are involved in creating and/or are taught to use the Matrix as part of their classroom management, they realize that (a) Intensity I or II inappropriate student behaviors should not be sent to the principal’s office, and (b) there will be administrative questions, training, coaching, or even personnel-related actions if they continue to send Intensity I or II behavior to the office.

The four Intensity Levels are briefly defined as follows:

- Intensity I (Annoying) Behavior: Behaviors in the classroom that are annoying or that mildly interrupt classroom instruction or student attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a minimum of interaction by using a corrective response (e.g., a non-verbal prompt or cue, physical proximity, a social skills prompt, reinforcing nearby students’ appropriate behavior).

_ _ _ _ _

- Intensity II (Disruptive or Interfering) Behavior: Behavior problems in the classroom that occur more frequently, for longer periods of time, or to the degree that they disrupt classroom instruction and/or interfere with student attention and engagement. Teachers handle these behaviors with a corrective response, and a classroom-based consequence (e.g., loss of student points or privileges, a classroom time-out, a note or call home, completion by the student of a behavior change plan).

After the consequence is over, and guided by the teacher, the student must positively practice the appropriate behavior that the student should have done and did not do (hence, requiring the consequence) at least three times as soon as possible.

_ _ _ _ _

- Intensity III (Persistently Disruptive or Antisocial) Behavior: Behavior problems in the classroom that significantly (as in a single incident) or persistently (as in multiple incidents that increase in severity over time) disrupt classroom instruction or engagement, or that involve antisocial acts toward adults or peers.

These inappropriate behaviors require some type of out-of-classroom response (e.g., a time-out in another teacher’s classroom, removal to a school “student accountability room,” an office discipline referral), and a consequence that involves the classroom teacher (even if, for example, an administrator is involved)—so that the student remains accountable to the teacher and the classroom where the behavior occurred.

The consequence could be followed by a restitutional pay-back (e.g., an apology, cleaning up/repairing damaged property or a messed-up classroom, community service), and should be followed by the positive practice of the appropriate behavior described in Intensity II above.

If it is believed or apparent that the inappropriate behavior is not a discipline problem but a social, emotional, behavioral, or psychoeducational problem, the student should be referred to the school’s Multi-Tiered Services (Child Study, Student Services) Team for assessments to determine the root cause(s) of the problem, and a resulting behavioral intervention plan that specifies the services, supports, strategies, or interventions that are both linked to the assessment results and needed to ameliorate the problem.

_ _ _ _ _

- Intensity IV (Severe or Dangerous) Behavior: These involve extremely antisocial, damaging, and/or dangerous behaviors—on a physical, social, or emotional level—that are typically cited and described in a District’s Student Code of Conduct handbook. These inappropriate behaviors require an immediate administrative referral and response (e.g., a parent conference, suspension, or expulsion), followed (at times) by additional consequences, restitutional requirements, and (once again) positive practice sessions.

While an administrator may, by Code, need to suspend a student, if she or he believes that the offense is not a discipline problem but a social, emotional, or behavioral problem, the student—as in the Intensity III description above—should be referred into the school’s Multi-Tiered Services and Supports process.

_ _ _ _ _

As noted, relative to disproportionality, when teachers consistently use the Intensity I, II, and III areas of the Matrix for all students, disproportionality is decreased or eliminated. This often occurs because the Matrix specifically discriminates between annoying (Intensity I) and disruptive behavior in the classroom (Intensity II)—explicitly identifying the different responses that facilitate students’ change of behavior.

When Administrators additionally hold teachers accountable for using the Matrix appropriately and consistently with all students, once again, disproportionality is effectively addressed.

When implementing the Behavioral Matrix process, schools need to use it with specific peer groups. This is because some peer groups have more social power, reinforcement, or influence over some individual students—reinforcing their inappropriate behavior and undermining school and classroom management. Here, the incentives and consequences built into the Matrix may need to be modified—both for the individual students and the peer groups involved.

_ _ _ _ _

Taken altogether, the Behavioral Matrix increases the probability that all students—including students of color—demonstrate the appropriate interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills described and taught in the second component above.

When all students—including students of color—decide to demonstrate inappropriate behavior, the Behavioral Matrix provides a predictable, but flexible and strategic, roadmap of proven practices that are focused on holding students accountable for their behavior, while motivating them to make a better choice the next time.

For teachers, the Behavioral Matrix also provides them a roadmap, but it especially addresses what needs to occur when students demonstrate Intensity I of II inappropriate behavior.

For administrators, the Behavioral Matrix provides guidance as to how to address serious student inappropriate behavior, and what to do when teachers send inappropriate “discipline” referrals to the office.

Over time, the Behavioral Matrix process helps schools and staff to discriminate and effectively address disciplinary problems and—from a multi-tiered perspective—social, emotional, and behavioral problems.

We have published an extensive number of resources that help schools to effectively develop and successfully implement the Behavioral Matrix process. For example, you may be interested in our Monograph:

Developing School Discipline Codes that Work: Increasing Student Responsibility while Decreasing Disproportionate Discipline Referrals

For more information:

[CLICK HERE for Behavioral Matrix RESOURCES]

_ _ _ _ _

Consistency and Fidelity

Consistency is a process. It would be great if we could “download” it into all students and staff. . . or put it in their annual flu shots. . . but that’s not going to happen.

Consistency needs to be “grown” experientially over time and, even then, it needs to be sustained in an ongoing way. It is grown through effective strategic planning with detailed implementation plans, good communication and collaboration, sound implementation and evaluation, and consensus-building coupled with constructive feedback and change.

It’s not easy. . . but it is necessary for school success. And it is especially important when working with students of color—who have been victimized by the system, and when implementing interventions for disproportionality.

More specifically, in order to be successful, staff (and students) need to (a) demonstrate consistent prosocial relationships and interactions—resulting in consistently positive and productive school and classroom environments; (b) communicate and maintain consistent behavioral expectations, while consistently teaching and practicing them; (c) use consistent incentives and consequences, while holding student consistently accountable for their appropriate behavior; and then (d) apply all of these components consistently across all of the settings, circumstances, and peer groups in the school.

Moreover, consistency occurs when staff interact similarly (a) with the same individual students, (b) across different students, and (c) within their grade levels or instructional groups. . . (d) across time, (e) across settings, and (f) across situations and circumstances.

Critically, when staff are inconsistent, students feel that they are being treated unfairly or that other students are being treated preferentially. As a result, they sometimes behave differently for different staff or in different settings, they can become manipulative— pitting one staff person against another, and they often emotionally react—some students getting angry with the inconsistency, and others simply withdrawing because they feel powerless to change it.

Said a different way: Inconsistency undercuts student motivation and accountability, and you don’t get the social, emotional, or behavioral interactions that you want from individual students, groups of students, or entire grade levels of students. . . in the classroom or in the common areas of the school.

Relative to Fidelity, a district or school may develop a multi-tiered “Disproportionality Action Plan” that is sound and well-prepared, specific and well-designed, research-based and proven, and well-staff and resourced. And yet, if there is no, poor, or inconsistent training, or if staff are not held accountable for implementation and results, the Plan may be implemented incompletely or improperly.

Thus, a lack of implementation fidelity will undermine and eventually doom any initiative—no matter how well designed or resourced.

_ _ _ _ _

Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The last of the evidence-based, interdependent components that districts and schools need at the center of their disproportionality recipe involve three “special situations”—the last of which requires a sound multi-tiered system of supports.

The first Special Situation focuses on the multiple settings in a school. Here, schools need to plan for student behavior and interactions not just in the classroom, but also in the common areas of the school—for example, the hallways, bathrooms, buses, cafeteria, and the playgrounds or common gathering areas.

It is important to understand that these common school areas are more complex and dynamic psychosocially than the classroom settings. Indeed, in these settings, there are typically more multi-aged or cross-grade students, more and more varied social interactions, more physical space or fewer explicit boundaries, fewer staff and supervisors, and different social demands.

As such, the positive student social, emotional, and behavioral interactions that may occur more easily in the classroom can be more taxed in the common school areas.

Accordingly, all students—including students of color—need to be taught how to demonstrate their interpersonal, social problem solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills in each common school area. Moreover, the training needs to be tailored to the social demands and expectations of these settings.

At the same time, staff who are supervising in these settings also need to be trained and coached to make sure that they are fairly and consistently (a) evaluating students’ behavior relative to the explicit expectations established for each setting; (b) prompting and reinforcing appropriate student behavior; and (c) responding to inappropriate behavior when exhibited by different students from different racial backgrounds.

_ _ _ _ _

The second Special Situation focuses on the impact of peer groups as psychosocial influencers, and their relationship to teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression (fighting).

As discussed in the Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skills Instruction and the Motivation and Accountability component sections, respectively, above, it is important to understand that the peer group is often a more dominant social and emotional “force”—relative to motivating or reinforcing individual students’ behavior—than the adults in a school.

As such, the school’s approaches to student behavior and self-management in the first four components must be consciously generalized and applied—relative to climate, relationships, behavioral expectations, skill instruction, motivation, and accountability—to ensuring that the peer group is an active positive and prosocial behavioral influence on individual students.

Thus, this component focuses on prevention and response strategies and approaches that focus all students—including students of color—on demonstrating appropriate behavior, and using productive ways to respond to negative peer interactions when they happen.

When the prevention strategies work, they eliminate the need for disciplinary actions that might end up being disproportionately weighted against students of color.

When the student response strategies work, students know how to respond to, for example, peer-instigated teasing, rejection, accusations, and social pressure—even when this occurs. In addition, because all of the students are trained in these strategies, this also prevents some negative peer interactions because the “aggressing” peer group knows that their “targets or victims” are prepared to respond appropriately to them.

All of this, once again, helps students who are being socially targeted or victimized from responding inappropriately and becoming part of a disciplinary action. It also teaches students who are bystanders to specific events how to effective respond when negative peer interactions occur. Finally, for socially inappropriate peer groups who nonetheless continue to “behave badly,” this component includes strategic or intensive multi-tiered interventions that are geared to eliminating the inappropriate interactions on the “front end.”

Because they are often peer events—and occur most often in the common areas of a school— activities in this Special Situations component extend to the prevention of and responses to peer-to-peer teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression. But the most important focus is teaching, motivating, and reinforcing the different peer groups in a school so that they are—especially at the secondary level—consistently prosocial contributors to the positive and safe culture, climate, norms, and interactions across the student body.

As an extension to addressing disproportionality, remember that classroom teachers, support staff, and administrators take an active role in all of this student and peer group instruction, motivation, and accountability.

As such, they are developing more intimate relationships with students of color, and the social problem-solving discussions help them to understand the backgrounds and social contexts of these students. Thus, when annoying or disruptive inappropriate behavior occurs with these same students of color, the teachers are more easily to move into a “Behavioral Matrix-based” problem-solving mode. . . rather than a rigid, sometimes race-based reactive mode that is based on discipline and not self-management.

_ _ _ _ _

The third Special Situation focuses on the fact that some student behavior occurs due to significant or intense idiosyncratic situations or circumstances that are not disciplinary in nature, but are part of their social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health make-up. As discussed earlier, these students often need multi-tiered strategic (Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) services, supports, strategies, or interventions that are based on functional or diagnostic assessments that determine the root causes of the students’ challenging behavior.

Examples of some of the triggers or causes of these social, emotional, and/or behavioral (not disciplinary) challenges include:

- Physical, Biological, Physiological, Genetic, Neurological issues

- Mental health issues

- Disabilities

- Significant stresses or traumas

- Dysfunctional home and family situations

- Poverty or Economic stresses

- Drugs, Alcohol, Vaping

- Significant Life Changes or Events

We know the students of color are at-risk in a number of the areas above. Indeed, this fact has been reinforced especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Relative to disproportionality, once again, it is important that teachers, support staff, and administrators discriminate between “discipline” and social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health student problems. While we are not saying that, using the Behavioral Matrix, students should not be sent to the principal’s office and/or suspended from school (the first time) after demonstrating an Intensity III or IV infraction. . . we are saying that, if we do not have the data that validates the discipline versus social, emotional, or behavior differentiation, the multi-tiered process needs to begin, and the office referrals and suspensions need to be reconsidered.

Said a different way: If teachers believe that an office referral and administrators believe that a suspension of a student of color (or any student) is the “strategic intervention” that will facilitate a student change of motivation or behavior, how many office referrals or suspensions are needed before the data tell you that that strategic intervention is not working. . . and that the building-level multidisciplinary Multi-Tiered Services Team needs to be involved in the case?

We have discussed the evidence-based, effective characteristics of a school-level multi-tiered system of support process in a number of past Blogs.

An excellent resource—that we used to guide districts’ and schools’ MTSS processes through our work at the Arkansas Department of Education for 13 years—is:

A Multi-Tiered Service and Support Implementation Guidebook for Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap

[CLICK HERE to Review this Resource]

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Summary

This two-part Blog Series was dedicated to helping districts and schools to successfully eliminate disproportionate discipline referrals and (punitive) actions for students of color.

In Part I of the Series, we presented a definition of “racism,” and talked about Critical Race Theory. We did this to emphasize that (a) the disproportionate disciplinary treatment of students of color—especially Black students (as well as students with disabilities)—has existed for decades, and that (b) initiatives to eliminate disproportionality should not be linked to the recent politicized conversation involving Critical Race Theory.

Relative to the latter area, we objectively reviewed the current information regarding Critical Race Theory and its presence in America’s classrooms. We expressed concerns about the impact that legislative and other policy-level actions—focused on restricting or eliminating the discussion of Critical Race Theory in schools—might have on teachers and students. And, we recommended that educators avoid wasting their time by looking past the Critical Race Theory politics and debate and, instead, focus directly on how to eliminate the disproportionate disciplinary referrals and actions against students of color—a long-standing result of racial bias in our schools.

Part I then discussed six different approaches that have been implemented in the past to address school-level disciplinary disproportionality—explaining why they have not worked and, hence, why they should be avoided in the future.

In this Part II, we addressed the six reasons/flaws from Part I by providing effective practices and solutions to decrease or eliminate disproportionality.

As part of this discussion, we directly addressed and dismissed an embedded issue in many of the race-based laws passed by different states during this year’s legislative sessions: the use of (especially, one-session in-service) anti-bias or diversity training with school staff members. Relative to disproportionality, however, we still clearly stated that staff who are specifically motivated by explicit bias and overt prejudice should be held directly accountable for discriminatory behavior, and that the recent state laws have not changed this professional (for administrators) responsibility.

The remainder of this Blog:

- Described five interdependent psychoeducational components and their specific, embedded practices (addressing Blog Part I’s Flaw #1); that are

- Organized within a strategically-implemented, evidence-based, multi-tiered professional development and coaching-centered whole-school initiative (addressing Flaw #2); that focuses on

- Teaching students—from preschool through high school—specific, observable, and measurable social, emotional, and behavioral self-management skills (addressing Flaws #3 and 5).

- We then advocated the use of a data-based problem-solving process—when students demonstrate frequent, persistent, unresponsive, significant, or extreme levels of inappropriate, disruptive, unpredictable, antisocial, or dangerous behavior—to objectively identify the root causes of the behavior, and to discriminate discipline problems from social, emotional, behavioral, and/or mental health problems. . . so that

- The assessment results can be linked to the strategic or intensive multi-tiered services, supports, strategies, or interventions that will eliminate the student problem and replace it—once again—with appropriate behavior (addressing Flaw #6).

Using the metaphor of a Master Chef who needs an excellent recipe and well-honed technical skills to prepare a world-class meal, the five interdependent psychoeducational components needed and discussed to eliminate disproportionality were:

- Positive Relationships and School/Classroom Climates

- Positive Behavioral Expectations and Skill Instruction

- Student Motivation and Accountability

- Consistency and Fidelity

- Special Situations and Multi-Tiered Services and Supports

The inherent principle grounding the evidence-based approach to disproportionality is:

- When all students (including students of color) are taught (in developmentally, culturally, and pedagogically-sound ways—from preschool through high school), and when they have mastered and can apply specific and scaffolded interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills... and

- When they are prompted, motivated, and held accountable for using these skills in all school settings and circumstances. . .

- They will consistently demonstrate appropriate, prosocial interactions. . . such that

- The need to need a disciplinary referral to the principal’s office will become moot.

In addition, as teachers, support staff, and administrators design, conduct, and apply this process, they will develop more intimate relationships with students of color that will help them to understand the backgrounds and social contexts of these students. Thus, when annoying or disruptive inappropriate behavior occurs with these same students of color, they can more easily to move into a self-management problem-solving mode—reacting more to the person than the person’s race.

_ _ _ _ _

As always, I hope that this Series was useful to you, and always look forward to your comments. . . whether on-line or via e-mail.

If I can help you in any of the components or multi-tiered areas discussed above, know that I am constantly working with districts and schools—virtually and on-site—in this important area. I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help you clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students.

As your school year enters the new school year, please accept my best wishes for a safe and productive one. . . one complete with active and positive student engagement, learning, and success.

Best,