The SEL Secret to Success: You Need to “Stop & Think” and “Make Good Choices”

Helping Students Learn and Demonstrate Emotional Control, Communication, and Coping

Awareness without Skills is Incomplete. A Plan without Action is a Waste.

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Over the past few weeks, as I have traveled to different consultations across the country, I have been reading Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl was incarcerated in the Nazi concentration camps during World War II, and he survived largely by focusing his mind, being, and existence on maintaining a meaning for his life even in the midst of horrific, hopeless, and harrowing circumstances.

As a psychotherapist, even in the death camps, Frankl also observed that those who found some meaning within or outside their imprisonment and daily abuse were the ones who had the highest probability of survival.

On a far different scale, I believe that we are all trying to find meaning in our personal and professional lives. And that is why I always try to consciously take the time to reflect on the “big ideas” that I have learned—about students, staff, schools, or systems—at the end of each week’s consultations.

This week, for example, I was able to visit six different schools in a demographically diverse urban/suburban school district—meeting with the counselors in each school.

The task was simple: To ask the counselors to identify the most pressing social, emotional, or behavioral issues or gaps in their respective schools, and what resources they needed from me through the five-year federal School Climate Transformation Grant that makes me available to them one full week per month.

Almost consistently, each counselor identified strikingly similar needs:

- Teaching students the interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills needed to mediate their within- and outside-of-school pressure points

- Helping teachers to build strong, positive, and sustained relationships with their students, to use effective and complementary classroom management strategies, and to discriminate among students with “discipline” problems versus those with social, emotional, behavioral, or mental health problems

- Discouraging teachers from sending students out of their classrooms—either to the Principal for discipline or to the Counselor for “counseling”—for mild to moderate disagreements, disengagements, or disruptions. . . encouraging them, instead, to use student conferences, collaborative problem-solving, consultations with colleagues and counselors (or other related services professionals), and (as warranted) classroom-based interventions

- The need for a structured, field-tested, and practical multi-tiered SEL process (not program) that results in increasing and maintaining students’ social, emotional, and behavioral accountability and self-management

What the counselors also shared—implicitly or explicitly—was the following:

- No one in their school really knew what “SEL” was, and many schools had different (and, sometimes, conflicting) perspectives, orientations, and committees for SEL, PBIS, and Restorative Practices, respectively;

- The schools were not using a concrete, research-proven blueprint to strategically guide, integrate, and evaluate their SEL/PBIS process—relative to both selecting and adding new elements, activities, or resources;

- Teachers’ 20-minutes of “mindfulness” with their students each morning was not producing meaningful or measurable student outcomes and, for many teachers, this time had (d)evolved into a “traditional, mindless” homeroom period where students “were supposed” to watch/listen to a “mindfulness video” or simply “checked in” for the day;

- Teachers’ classroom circles or meetings were similarly disconnected, unfocused, and unproductive. . . with some having lost the expected goals and outcomes, and others being dominated by the same students consistently identifying the same irritating issues caused by the same peers; and

- Most staff were dissatisfied with the circumstances above, but (a) many teachers had to prioritize academics over students’ social, emotional, or behavioral status; and (b) many counselors, administrators, and other related services professionals were doing the best they could (in pulling resources down from the internet), but truly “did not know what they did not know” in these social, emotional, and behavioral (Tier I) areas.

Students’ Emotional Control, Communication, and Coping

While the Counselors identified so many critical needs, and we could write hundreds of Blogs (or books) on each one. . .

[and we HAVE discussed many of these issues in many of our past Blogs—check them out using the chronological Archive or the indexed Categories at our Blog site: https://www.projectachieve.info/blog] . . .

let's focus on the need for students to learn how to leverage their emotional awareness so that, over time, they can independently demonstrate emotional control, communication, and coping skills.

Unfortunately, some colleagues frame these skills using vague, global, and constructivist terms like “emotional self-regulation”. . . and then they advocate unproven or similarly global strategies (like “mindfulness”).

In contrast, we advocate explicitly defined, observable, and measurable outcomes, which are anchored by established, science-to-practice emotional, cognitive, and behavioral strategies.

As such, Emotional Awareness involves:

- Students’ identification, knowledge, understanding, and discrimination of the many different emotions that they may experience in their lives;

- Their awareness of the emotional triggers that exist in the settings that they go to or must attend;

- Their awareness of their physiological cues and responses to different emotional situations; and

- Their awareness of how others look and act when they are in different emotional situations or states.

_ _ _ _ _

Emotional Control and Communication occurs:

- When students are able to maintain the physiological control of their bodies when under conditions of emotionality, so that

- They are able to think clearly and rationally—demonstrating effective social problem-solving skills, so that

- They can demonstrate appropriate social interactions and behavioral self-management skills.

_ _ _ _ _

Emotional Coping:

- Goes beyond emotional control to the point where a student is able to consciously process a personal or interpersonal situation in order to master, minimize, or tolerate the stress and conflict. Coping includes accepting someone else’s emotional support.

- Emotional coping occurs when students debrief and reconcile a just-concluded emotional situation and/or learn to minimize the emotional impact of a persistent or traumatic situation.

- Ultimately, emotional coping skills help students to (continue to) live their lives in emotionally positive and healthy ways—even in the face of continuing, similar, or new traumatic situations (or those that trigger emotional memories).

_ _ _ _ _

And all of this combines as students demonstrate, for example, the following strategies or situational responses:

- Avoiding Trouble/Conflict Situations

- Deciding Whether to Follow the Group

- Dealing with Peer Pressure

- Being Honest/Acknowledging your Mistakes

- Apologizing/Excusing Yourself

- Dealing with Teasing

- Dealing with Being Rejected or Left Out

- Dealing with Losing or Not Attaining Desired Goals

- Showing Understanding of Another’s Feelings/Empathy

- Dealing with and Responding to Another Person’s Anger or Emotionality

- Walking Away from a Fight/Conflict

- Negotiating to Resolve Conflicts Peacefully and Productively

_ _ _ _ _

From a science-to-practice perspective, then:

- Emotional Awareness develops through instruction, personal and social understanding, learning and coaching, application and feedback, and evaluation, mastery, and maturation.

- Emotional Control and Communication occurs when there is physiological control, emotional self-control, attributional/attitudinal control, and behavioral control and execution.

- Emotional Coping develops through students’ emotional awareness, and the use of emotional and attributional control skills that are integrated into coping strategies. Hundreds of social, emotional, and behavioral coping strategies have been identified in both research and practice.

The SEL Secret to Success

Our opening quote stated:

Awareness without Skills is Incomplete. A Plan without Action is a Waste.

While multiple applications of this quote are possible, we want to emphasize that teaching students to accurately recognize, label, and discuss their emotions is but the first step in teaching emotional control, communication, and coping.

Indeed, if students—concurrently, and in response to real-life classroom, peer, and school situations—are not explicitly taught how to move from emotional awareness to planning and demonstrating effective (a) emotional and physiological control, (b) social and interpersonal communication, (c) conflict prevention and resolution skills, and (d) short- and long-term coping strategies, then the potential that begins with awareness most likely will not result in real and sustained outcomes.

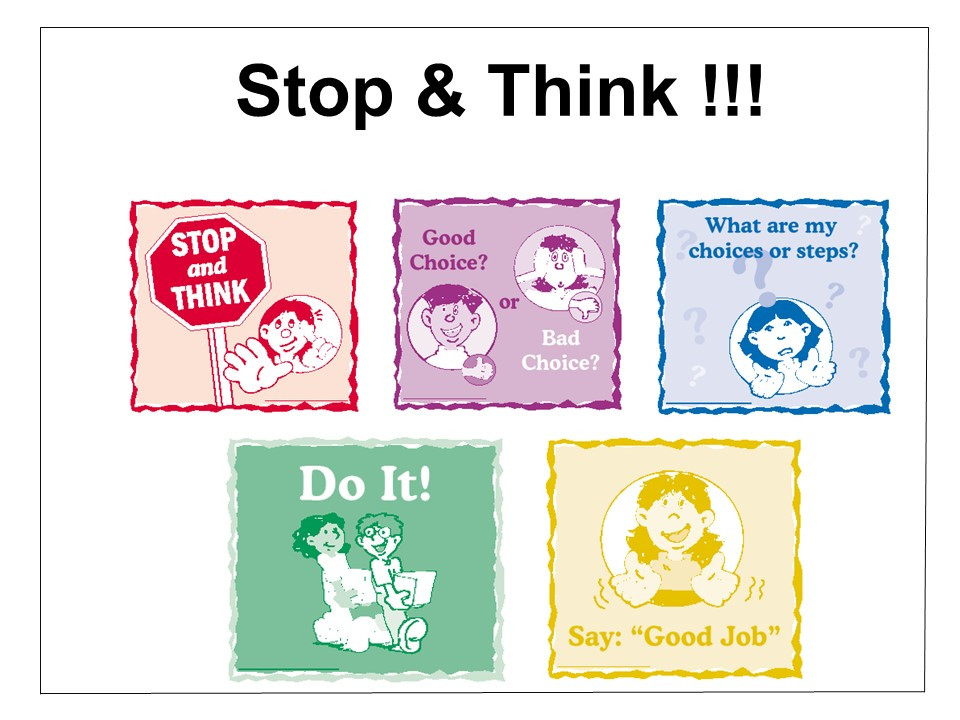

For us, the foundation to bridging and integrating these emotional, cognitive, and behavioral (SEL) domains—and to produce real outcomes—begins with the Stop & Think universal language that we use to teach all of the skills in our Stop & Think Social Skills Program.

Once internalized, this science-to-practice language is used by students to guide them through a social problem-solving process that helps them to (a) maintain their emotional control, (b) think clearly, (c) plan strategically, and (d) implement needed social or conflict resolution skills confidently.

This is the SEL Secret to Success!

The core Stop & Think language involves five steps that can be modified as they are mastered by students, or are adapted—especially in Step 2—when students “push back” and exhibit resistance or persistent challenges.

The Steps are:

- I need to Stop and Think!

- Am I going to make a Good Choice or Bad Choice? I need to make a Good Choice.

- What are my (good) Choices or Steps?

- Now, I’m going to just Do It!

- Great! Now I can tell myself that I did a Good Job!

Here is a brief description of the scientific foundation, use, and contributions of these steps:

Step 1

The Stop and Think! step is a self-control, impulse-control, and/or self-management step designed to classically condition students (a la Pavlov) to stop and take the time necessary to remain calm (or calm down) and control their emotions, so that they can think about how they want to handle a situation.

For emotional situations, we condition this language and momentary stopping behavior to students’ emotional triggers. This results in an almost involuntary physical and emotional pause before students (a) react in an overly-emotional way and/or (b) respond inappropriately without thinking.

The Stop and Think! step is neurologically focused on the brain’s amygdala and limbic system. . . helping students to control their fight, flight, or freeze responses to emotional situations. This emotional control then allows students to move to Step 2—which requires them to use the executive functioning and social problem-solving strategies housed in the brains’ cortex.

_ _ _ _ _

Step 2

The Good Choice or Bad Choice? step is an operant conditioning step (a la Skinner) that motivates students to reject the Bad Choices that could be chosen to (inappropriately) handle specific social or interpersonal situations and, instead, to choose, plan, and demonstrate one or more Good Choices.

Here, students are taught—after stopping and now thinking—to consider the consequences of making a Bad Choice, and/or the incentives of making a Good Choice.

Parenthetically, incentives and consequences are both used to motivate appropriate student (or anyone’s) behavior. Critically, consequences are different than punishment which (the latter) typically is used to stop inappropriate behavior. At times, punishment is successful, but it often (a) models poor social problem-solving and emotional control; (b) is inconsistent with developing or maintaining good rapport and positive relationships with students; and (c) may result in students next exhibiting yet another different but inappropriate behavior that is not also being punished at the same time.

In a classroom or common school area, teachers and other staff need to make sure that (a) incentives and consequences are explicit to students; that (b) they are motivationally meaningful and powerful to students; that (c) there are enough different incentives and consequences available so that they can be individualized to different students; and (d) that they are delivered consistently by all staff.

In this regard, when specific social skills are taught to students the first time, the teachers leading the lessons need to guide students through a discussion that includes these questions:

“What negative outcomes or consequences will occur if you make a Bad Choice and either do not demonstrate this skill or demonstrate it in an incorrect way?”

“What positive outcomes or incentives will occur if you make a Good Choice and use this skill, implementing it in a correct way?”

Ultimately, once internalized, students will routinely complete Step 2 in their heads, concluding that, “I’m going to make a Good Choice.”

This decision not only motivates students to actually make a Good Choice in Step 4, but also to think only about “good choices and/or steps” as they proceed through Step 3.

_ _ _ _ _

Step 3

The What are your Choices or Steps? step uses cognitive-behavioral psychology and mediational learning (a la Meichenbaum and Bandura) to help organize, prepare, and script students to think about the appropriate steps and related behaviors of a specific skill or interaction that is needed in an emotionally-challenging situation.

This is where teachers teach the specific “skills scripts” for each Stop & Think skill so that students learn and are able to demonstrate (in Step 4) their Good Choices—that is, their prosocial, conflict resolution, and/or coping skills—even under conditions of emotionality.

Thus, this is also the Step that teachers especially focus on as they guide student roleplays—during their social skill lessons—with increasing levels of (simulated) emotional conditions.

One ultimate goal here is to teach students how to maintain the initial emotional control accomplished in the Stop & Think step (Step 1), such that they can perform the behavioral actions needed (in Steps 3 and 4) while still in or experiencing significantly tense emotional situations.

A second ultimate goal is to neurobehaviorally condition students to “Think (Step 3) before they Act (Step 4),” countering what students often do in emotional situations when they “Act (Step 4) before they Think (Step 3).”

_ _ _ _ _

As students process through Step 3 of the Stop & Think language, they can use two types of skill scripts—scripts that are organized in a step-by-step sequential fashion (“Step” skills), or scripts where students need to consider and select one of a number of possible good choices (“Choice” skills).

Because of their developmental status, younger students (through Grade 3) typically use scripts that involve Step skills, while older students (Grade 4 and above) can learn and use the higher-ordered thinking scripts that employ Choice skills.

For example, the Grade 1 “Dealing with Teasing” Step 3 skill script below is organized as a Step skill because, developmentally, students are most successful here when they go from step to step in the script sequence—stopping only when a specific step leads to a successful resolution of the situation.

What are your Choices or Steps? You should:

- Take deep breaths and count to five.

- Ignore the person who is teasing you.

- Ask the person to stop in a nice way.

- Walk away.

- Find an adult for help.

The Grade 5 “Dealing with Teasing” Step 3 skill script below is organized as a Choice skill because students at this level have the cognitive-developmental ability to evaluate a specific teasing situation, eventually selecting the best choice from a number of possible “Good Choice” options.

What are your Choices or Steps? You should:

- Take deep breaths and count to five.

- Think about your good choices. You can:

a. Ignore the person who is teasing you.

b. Ask the person to stop in a nice way.

c. Walk away.

d. Find an adult for help.

- Choose and Act Out your best choice.

_ _ _ _ _

When students are applying the Stop & Think language for emotional control, communication, and coping situations, they always begin Step 3 with a “Take deep breaths and count to five (or ten, or more)” step.

Because this emotional control or de-escalation step neurologically targets the brain’s amygdala, and because—in emotional situations—the amygdala activates before the cortex or thinking/executive functioning part of the brain, the Stop & Think language is modified so that students say:

“I need to Stop & Think (Step 1), Make a Good Choice (Step 3), and Take my Deep Breaths (the beginning part of Step 3).”

When conditioned, internalized, and automatically used by students in emotionally-triggering situations, this modified, internal language Stop & Think script offers the highest probability that they will successfully control their emotions, communicate or interact effectively, and cope with the situation at-hand.

_ _ _ _ _

Step 4

Once students have thought about the good social skill steps or choices needed for a particular skill or emotionally-triggering situation (Step 3), they are ready to behaviorally demonstrate them.

Thus, in the (just) Do It! step (Step 4), students behaviorally carry out their plan, implement the social skill steps chosen, and evaluate whether or not it has worked.

When teaching younger elementary school-aged students, teachers may need to repeat the skill steps as their students follow them in Step 4, and they might need to physically guide some students through specific skill-related behaviors.

Older students, with prompting, practice, and self-monitoring over time, will eventually echo the Stop & Think steps and scripts silently to themselves, performing their prosocial behaviors more independently and automatically over time.

If the Do It! step (Step 4) works, then students can proceed to Step 5.

If the situation is not resolved or the behavior doesn’t work in Step 4, then students simply return to the Step 3 skill script, review and prepare it more carefully, or choose another (or the next) Good Choice option in the script.

If the skill still doesn’t work, students are prompted to identify another possible social skill or approach to deal with the situation, and/or to find a peer or adult who can provide feedback and assistance.

_ _ _ _ _

Step 5

The Good Job! step (Step 5) uses the cognitive-behavioral skill of self-reinforcement as students reinforce themselves for successfully using a social skill to respond appropriately and successfully to an emotional situation or dilemma.

This step is important because students should not become dependent or have to wait on others (especially adults) to tell them that they have done a good job. Self-reinforcement also helps students to deal with negative peer pressure or reinforcement—the times when peer groups do not value and/or will not reinforce the Good Choices that should occur in a social or emotionally-involved situation.

Over time and practice, Step 5 helps students to independently recognize when they are successful, and how to effectively reinforce themselves for a job well done. This is an essential step in the emotional coping and self-management process.

Summary

This Blog began by describing the most pressing social, emotional, or behavioral student (and staff) issues or gaps—identified by Counselors in interviews with me this past week. These issue and gaps represent the concerns of educators across the country.

Focusing especially on the fact that students have not learned and/or are not consistently demonstrating effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional control, communication, and coping skills, we summarized the counselors’ implicit and explicit observations regarding SEL in their schools:

- No one in their school really knew what “SEL” was, and many schools had different (and, sometimes, conflicting) perspectives, orientations, and committees for SEL, PBIS, and Restorative Practices, respectively;

- The schools were not using a concrete, research-proven blueprint to strategically guide, integrate, and evaluate their SEL/PBIS process—relative to both selecting and adding new elements, activities, or resources;

- Teachers’ 20-minutes of “mindfulness” with their students each morning was not producing meaningful or measurable student outcomes and, for many teachers, this time had (d)evolved into a “traditional, mindless” homeroom period where students “were supposed” to watch/listen to a “mindfulness video” or simply “checked in” for the day;

- Teachers’ classroom circles or meetings were similarly disconnected, unfocused, and unproductive. . . with some having lost the expected goals and outcomes, and others being dominated by the same students consistently identifying the same irritating issues caused by the same peers; and

- Most staff were dissatisfied with the circumstances above, but (a) many teachers had to prioritize academics over students’ social, emotional, or behavioral status; and (b) many counselors, administrators, and other related services professionals were doing the best they could (in pulling resources down from the internet), but truly “did not know what they did not know” in these social, emotional, and behavioral (Tier I) areas.

_ _ _ _ _

Focusing on, defining, and identifying how students should exhibit emotional control, communication, and coping skills in their classrooms and across the common areas of the school, we then shared the SEL Secret to Success—the evidence-based Stop & Think Social Skills universal language:

- I need to Stop and Think!

- Am I going to make a Good Choice or Bad Choice? I need to make a Good Choice.

- What are my (good) Choices or Steps?

- Now, I’m going to just Do It!

- Great! Now I can tell myself that I did a Good Job!

The scientific foundation, use, and contributions of these steps were then described.

_ _ _ _ _

More Resources

Our experience in training educators and related services professionals (counselors, school psychologists, social workers, special education teachers, applied behavioral specialists) to implement the Stop & Think Social Skills process in thousands of schools over the past 30+ years has resulted—as objectively measured using multiple measures and observed student behavior over time—in the outcomes identified by our Counselors this week, and that are the core outcomes of any SEL initiative.

Clearly, success does not occur with all students. That is why any SEL initiative must have a multi-tiered continuum of services, supports, strategies, and interventions for students needing more intensive attention.

For those who would like to see the Stop & Think process in more action (albeit through our Stop & Think Parenting Program), a free 46-minute on-line/on-demand video is available at:

[CLICK HERE for Free Stop & Think Video]

_ _ _ _ _

For those interested in reading about the current state of SEL in our country—what is being done, and what should be done, please feel free to consult the following recent Blogs:

October 23, 2021: Addressing Students’ SEL Pandemic Needs by Addressing their SEL Universal Needs. What Social, Emotional, Attributional, and Behavioral Skills Do ALL Students Need from an SEL Initiative? (Part I)

_ _ _ _ _

November 6, 2021. The Current State of SEL in our Schools: The Frenzy, Flaws, and Fads. If the Goal is to Teach Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skills, Why are We Getting on the Wrong Trains Headed “West”?(Part II)

_ _ _ _ _

With all of the social, emotional, and behavioral student and staff needs in our schools, it only makes sense to implement the science-to-practice strategies that have demonstrated their success in demographically diverse schools across the country.

Today’s “SEL Secret” is just the beginning. But this beginning can set the tone for a schoolwide initiative that best addresses the student, staff, and school outcomes that we all want—and that everyone, especially given the events of the past two years—needs.

I appreciate everyone who reads this bi-monthly Blog and thinks about the issues or recommendations that we share.

As always, if I can help you in any of the SEL areas discussed in this message, I am always happy to provide a free one-hour consultation conference call to help clarify your needs and directions on behalf of your students and colleagues.

You, too, can be one of the many districts or schools that have seized this post-Blog opportunity. I hope to hear from you soon.

Best,