Revisiting Title IX’s Sexual Harassment Requirements While Avoiding Secondary Victimization: A Procedural Primer

Why Do Too Many Districts Not Know (or Abdicate) their Responsibilities?

[To listen to a synopsis and analysis of this Blog on the “Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive” podcast on Spotify. . . hosted by popular AI Educators, Angela Jones and Davey Johnson: CLICK HERE for Angela and Davey’s Enlightening Discussion]

Dear Colleagues,

Introduction

Today, we’re going to have a very straightforward, factual discussion.

The “backstory” involves the last few Expert Witness court cases that I have been involved in. . . in different states. In all of these cases, I am supporting different adolescent girls who were sexually assaulted by male peers on school grounds.

As such, the cases involve Title IX (2020) regulations (Part 106—Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance).

Through these cases, I am finding that—even though this is Federal law—many school administrators and educators either do not know that (a) Title IX has an entire section addressing Sexual Harassment; and (b) this section requires a series of very specific responses and actions.

These are codified in Title IX’s Subpart D—Discrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Prohibited (primarily, §106.44 Recipient's response to sexual harassment; and §106.45 Grievance process for formal complaints of sexual harassment).

The first Bottom Line is that a district must substantively respond to a sexual harassment allegation when it occurs in one of its schools.

It cannot abdicate this responsibility by only turning the case over to Law Enforcement.

Here, as Joe Friday would say (look him up), are the facts.

Definitions from Title IX

To begin our journey, consider the following verbatim Title IX definitions:

Sexual harassment means conduct on the basis of sex that satisfies one or more of the following:

An employee of the recipient conditioning the provision of an aid, benefit, or service of the recipient on an individual's participation in unwelcome sexual conduct;

Unwelcome conduct determined by a reasonable person to be so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the recipient's education program or activity; or

“Sexual assault” as defined in 20 U.S.C. 1092(f)(6)(A)(v), “dating violence” as defined in 34 U.S.C. 12291(a)(10), “domestic violence” as defined in 34 U.S.C. 12291(a)(8), or “stalking” as defined in 34 U.S.C. 12291(a)(30).

_ _ _ _ _

Actual knowledge means notice of sexual harassment or allegations of sexual harassment to a recipient's Title IX Coordinator or any official of the recipient who has authority to institute corrective measures on behalf of the recipient, or to any employee of an elementary and secondary school.

“Notice” as used in this paragraph includes, but is not limited to, a report of sexual harassment to the Title IX Coordinator as described in §106.8(a).

_ _ _ _ _

Complainant means an individual who is alleged to be the victim of conduct that could constitute sexual harassment.

_ _ _ _ _

Respondent means an individual who has been reported to be the perpetrator of conduct that could constitute sexual harassment.

_ _ _ _ _

Formal complaint means a document filed by a Complainant or signed by the Title IX Coordinator alleging sexual harassment against a Respondent and requesting that the recipient investigate the allegation of sexual harassment.

At the time of filing a formal complaint, a Complainant must be participating in or attempting to participate in the education program or activity of the recipient with which the formal complaint is filed. A formal complaint may be filed with the Title IX Coordinator in person, by mail, or by electronic mail, by using the contact information required to be listed for the Title IX Coordinator under §106.8(a), and by any additional method designated by the recipient.

As used in this paragraph, the phrase “document filed by a Complainant” means a document or electronic submission (such as by electronic mail or through an online portal provided for this purpose by the recipient) that contains the Complainant's physical or digital signature, or otherwise indicates that the Complainant is the person filing the formal complaint. Where the Title IX Coordinator signs a formal complaint, the Title IX Coordinator is not a Complainant or otherwise a party under this part or under §106.45, and must comply with the requirements of this part, including §106.45(b)(1)(iii).

_ _ _ _ _

Supportive measures means non-disciplinary, non-punitive individualized services offered as appropriate, as reasonably available, and without fee or charge to the Complainant or the Respondent before or after the filing of a formal complaint or where no formal complaint has been filed. Such measures are designed to restore or preserve equal access to the recipient's education program or activity without unreasonably burdening the other party, including measures designed to protect the safety of all parties or the recipient's educational environment, or deter sexual harassment.

Supportive measures may include counseling, extensions of deadlines or other course-related adjustments, modifications of work or class schedules, campus escort services, mutual restrictions on contact between the parties, changes in work or housing locations, leaves of absence, increased security and monitoring of certain areas of the campus, and other similar measures.

The recipient must maintain as confidential any supportive measures provided to the Complainant or Respondent, to the extent that maintaining such confidentiality would not impair the ability of the recipient to provide the supportive measures.

The Title IX Coordinator is responsible for coordinating the effective implementation of supportive measures.

_ _ _ _ _

Critically, Title IX also addresses sexual harassment through social media. While school-conducted Title IX investigations have increasingly considered private and public social media communications and posts, whether social media activity can be used as evidence in a hearing depends on the school’s sexual harassment and student conduct policy or its jurisdiction to discipline students and faculty members for off-campus behavior.

Thus, districts—often required by state law—really must have their own written and School Board-passed Sexual (and other) Harassment polic(ies) that conform to both Federal and state law (more on this later).

Important and Required Title IX Sexual Harassment Procedures

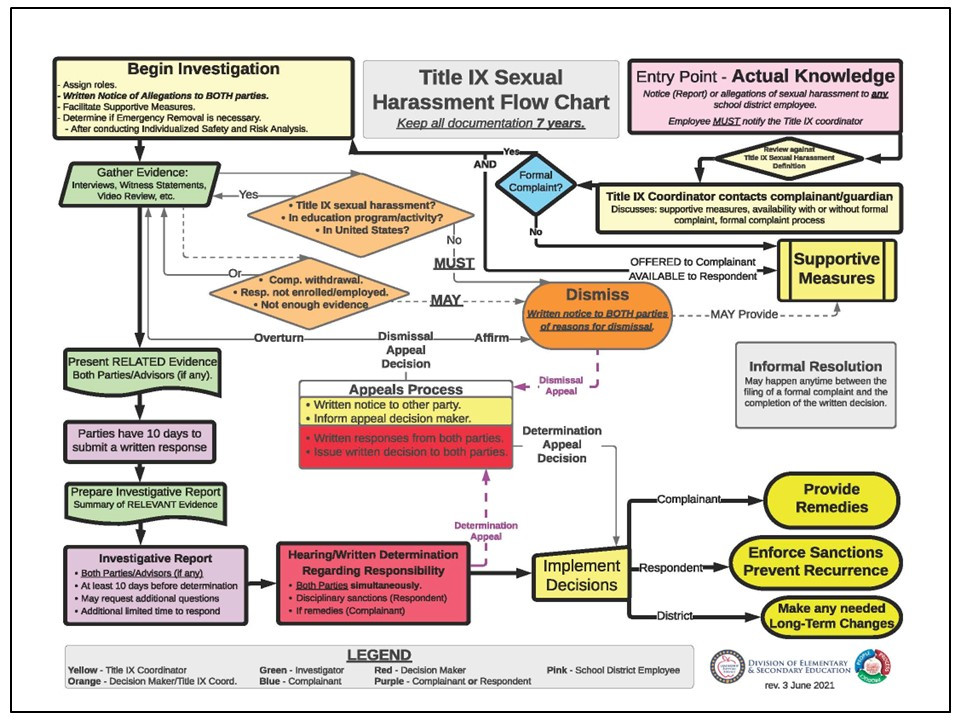

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education published the Title IX procedural Flowchart below in June 2021.

As is evident in the upper right-hand section of the Flowchart, when any school employee receives a notice (Report) or allegation of sexual harassment, the staff member must notify the District’s Title IX Coordinator (who must always be duly designated by and present in the District).

This means that the allegation does not have to be proven at the beginning of the process. Indeed, this is one reason why the process exists.

Moreover, it also means that, for example, a school staff member or administrator can conduct their own investigation and independently conclude that “there was not sexual harassment here”. . . and not report it to the Title IX Coordinator.

Finally, it means that (a) a staff member who does not notify the Title IX Coordinator is at-risk of a disciplinary action by the District, because (b) that staff member is responsible for causing the District to be out-of-compliance with this Federal law.

At this point, at least the following should occur:

- The Title IX Coordinator has a “prompt” meeting with the Complainant (and his or her parents/guardians) to (a) discuss the availability of supportive measures as defined in §106.30—with or without the filing of a formal complaint, (b) consider the student’s wishes relative to supportive measures, and (c) explain the process for filing a formal complaint.

Note that it is the student’s decision to proceed (or not) with a formal complaint.

Critically, by not meeting with the student—and either dismissing the case or proceeding independently with a formal complaint, the District is de facto and inappropriately making the decision for the student.

NOTE: If, per State law, the District must involve Child Protective Services and/or Law Enforcement, then that needs to occur and be communicated to the parents/guardians and (as appropriate) the student.

BUT: There are no statements in Title IX that preclude a simultaneous investigation involving both the District and law enforcement, and Title IX says that the district must conduct a formal investigation if requested by the Complainant.

While simultaneous or parallel District and Law Enforcement investigations need to be coordinated to ensure the integrity of their respective fact-finding and decision-making processes, the decision to proceed with a District-level formal complaint—once again—rests with the allegedly aggrieved student.

_ _ _ _ _

- At the beginning of the formal complaint/grievance process, a within-District or external individual or entity could be appointed by the District’s Title IX Coordinator to conduct an investigation.

The investigation must treat “Complainants and Respondents equitably by providing remedies to a Complainant where a determination of responsibility for sexual harassment has been made against the Respondent, and. . . by following a grievance process. . . before the imposition of any disciplinary sanctions or other actions that are not supportive measures as defined in §106.30, against a Respondent.”

_ _ _ _ _

- In enacting this process, the District must ensure “an equal opportunity for the parties to present witnesses [34 C.F.R. §106.45(b)(5)(ii)], provide an opportunity to review all evidence [id. at (b)(5)(vi)]; and create an investigative report summary of the evidence [id. at (b)(5)(vii)]. With or without a hearing, following the investigative report, each side is permitted to submit questions to the other party or witnesses [34 C.F.R. §106.45(b)(6)].”

_ _ _ _ _

- Finally, the individual appointed to make a final case decision cannot be the Title IX Coordinator or the investigator [34 C.F.R. §106.45(b)(7)]. This decision-maker must issue a “written determination” with findings of fact, conclusions, a determination regarding responsibility, disciplinary sanctions, and remedies [Id. at (b)(7)(ii)(C),(D)(E)].

_ _ _ _ _

Early on, it is recommended that the Title IX Coordinator facilitate a process whereby a decision is made on the need to protect the Complainant through an Emergency Removal.

Title IX states:

Emergency removal. Nothing in this part precludes a recipient from removing a Respondent from the recipient's education program or activity on an emergency basis, provided that the recipient undertakes an individualized safety and risk analysis, determines that an immediate threat to the physical health or safety of any student or other individual arising from the allegations of sexual harassment justifies removal, and provides the Respondent with notice and an opportunity to challenge the decision immediately following the removal. This provision may not be construed to modify any rights under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, or the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Sample District Policy Statements

The U.S. Department of Education has a number of resource documents to help districts successfully follow Title IX’s regulations. These include (a) the Regulations themselves; (b) a Fact Sheet; (c) a Question and Answer document; and (d) a number of webinars and blogs.

Most can be found at the following link:

[CLICK HERE for Title IX Resources]

In one of the linked U.S. Department of Education resources, some sample District Policy Statements in different areas of Title IX are suggested.

Below are a few:

Receiving and Responding to Reports of Sexual Harassment

When a complaint or report of sexual harassment is made under this school’s policy, the Title IX Coordinator (or designee) will: (1) confidentially contact the Complainant to offer supportive measures, consider the Complainant’s wishes with respect to supportive measures, and inform them of the availability of supportive measures with or without filing a formal complaint; (2) explain the process for how to file a formal complaint; (3) inform the Complainant that any report made in good faith will not result in discipline; and (4) respect the Complainant’s wishes with respect to whether to investigate, unless the Title IX Coordinator determines it is necessary to pursue the complaint in light of a health or safety concern for the community.

_ _ _ _ _

Supportive Measures

Supportive measures are available regardless of whether the Complainant chooses to pursue any action under this school’s policy, including before and after the filing of a formal complaint or where no formal complaint has been filed. Supportive measures are available to the Complainant, Respondent, and, as appropriate, witnesses or other impacted individuals. The Title IX Coordinator will maintain consistent contact with the parties to ensure that safety and emotional and physical well-being are being addressed. Generally, supportive measures are meant to be short-term in nature and will be re-evaluated on a periodic basis. To the extent there is a continuing need for supportive measures after the conclusion of the resolution process, the Title IX Coordinator will work with appropriate school resources to provide continued assistance to the parties.

_ _ _ _ _

Investigations

Once a formal Title IX complaint is filed, an investigator will be assigned and the parties will be treated equitably, including in the provision of supportive measures and remedies. They will receive notice of the specifics of the allegations as known, and as any arise during the investigation. The investigator will be unbiased and free from conflicts of interest and will objectively review the complaint, any evidence, and any information from witnesses, expert witnesses, and the parties. The investigation may include, among other things, interviewing the Complainant, the Respondent, and any witnesses; reviewing law enforcement investigation documents if applicable; reviewing relevant student or employment files (preserving confidentiality wherever necessary); and gathering and examining other relevant documents, social media, and evidence. If the investigator conducts interviews, the parties will be provided time to prepare and will receive notice of the time/date/location/participants/purpose for the interviews.

_ _ _ _ _

Hearing format

While the hearing is not intended to be a repeat of the investigation, the parties will be provided with an equal opportunity for their advisors to conduct cross-examination of the other party and of relevant witnesses. A typical hearing may include: brief opening remarks by the decision-maker; questions posed by the decision-maker to one or both of the parties; cross-examination by either party’s advisor of the other party and relevant witnesses; and questions posed by the decision-maker to any relevant witnesses.

_ _ _ _ _

Confidentiality

The hearing is a closed proceeding and is not open to the public. All participants involved in a hearing are expected to respect the seriousness of the matter and the privacy of the individuals involved. The school’s expectation of privacy during the hearing process should not be understood to limit any legal rights of the parties during or after the resolution. The school may not, by federal law, prohibit the Complainant from disclosing the final outcome of a formal complaint process (after any appeals are concluded). All other conditions for disclosure of hearing records and outcomes are governed by the school’s obligations under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), any other applicable privacy laws, and professional ethical standards.

_ _ _ _ _

Restrictions on Considering a Complainant’s or Respondent’s Sexual History

The investigator will not, as a general rule, consider the sexual history of a Complainant or Respondent. However, in limited circumstances, sexual history may be directly relevant to the investigation. As to Complainants: While the investigator will never assume that a past sexual relationship between the parties means the Complainant consented to the specific conduct under investigation, evidence of how the parties communicated consent in past consensual encounters may help the investigator understand whether the Respondent reasonably believed consent was given during the encounter under investigation. Further, evidence of specific past sexual encounters may be relevant to whether someone other than Respondent was the source of relevant physical evidence. As to Respondents: Sexual history of a Respondent might be relevant to show a pattern of behavior by Respondent or resolve another issue of importance in the investigation. Sexual history evidence that is being proffered to show a party’s reputation or character will never be considered relevant on its own.

_ _ _ _ _

Determination Regarding Responsibility

The school will review the evidence provided by all parties and will make a final determination of responsibility after the investigation. The decision-maker will not be the Title IX Coordinator, the investigator, or any other individual who may have a conflict of interest. The final determination will be provided to the parties at the same time, with appeal rights provided. It will explain if any policies were violated, the steps and methods taken to investigate, the findings of the investigation, conclusions about the findings, the ultimate determination and the reasons for it, any disciplinary sanctions that will be imposed on the Respondent, and any remedies available to the Complainant to restore or preserve equal access.

The decision-maker will issue a written determination following the review of evidence. The written determination will include: (1) identification of allegations potentially constituting sexual harassment as defined in 34 C.F.R. § 106.30; (2) a description of the procedural steps taken from the receipt of the complaint through the determination, including any notifications to the parties, interviews with parties and witnesses, site visits, and methods used to gather evidence; (3) findings of fact supporting the determination, conclusions regarding the application of this formal grievance process to the facts; (4) a statement of, and rationale for, the result as to each allegation, including any determination regarding responsibility, any disciplinary sanctions the decision-maker imposed on the Respondent that directly relate to the Complainant, and whether remedies designed to restore or preserve equal access to the school’s education program or activity will be provided to the Complainant; and (5) procedures and permissible bases for the parties to appeal the determination. The written determination will be provided to the parties simultaneously. Remedies and supportive measures that do not impact the Respondent should not be disclosed in the written determination; rather the determination should simply state that remedies will be provided to the Complainant.

_ _ _ _ _

Sanctions and Remedies

When a Respondent is found responsible for the prohibited behavior as alleged, sanctions are based on the severity and circumstances of the behavior. Disciplinary actions or consequences can range from a conference with the Respondent and a school official through suspension or expulsion. When a Respondent is found responsible for the prohibited behavior as alleged, remedies must be provided to the Complainant. Remedies are designed to maintain the Complainant’s equal access to education and may include supportive measures or remedies that are punitive or would pose a burden to the Respondent.

Whatever the outcome of the investigation, hearing, or appeal, the Complainant and Respondent may request ongoing or additional supportive measures. Ongoing supportive measures that do not unreasonably burden a party may be considered and provided even if the Respondent is found not responsible.

_ _ _ _ _

Appeals

Each party may appeal (1) the dismissal of a formal complaint or any included allegations and/or (2) a determination regarding responsibility. To appeal, a party must submit their written appeal within five business days of being notified of the decision, including the grounds for the appeal. The grounds for appeal are as follows: Procedural irregularity that affected the outcome of the matter (i.e., a failure to follow the institution’s own procedures); New evidence that was not reasonably available at the time the determination regarding responsibility or dismissal was made, that could affect the outcome of the matter; The Title IX Coordinator, investigator(s), or decision- maker(s) had a conflict of interest or bias for or against an individual party, or for or against Complainants or Respondents in general, that affected the outcome of the matter. The submission of an appeal stays any sanctions for the pendency of an appeal. Supportive measures and remote learning opportunities remain available during the pendency of the appeal. If a party appeals, the school will as soon as practicable notify the other party in writing of the appeal; however the time for appeal shall be offered equitably to all parties and shall not be extended for any party solely because the other party filed an appeal. Appeals will be decided by an individual, who will be free of conflict of interest and bias, and will not serve as investigator, Title IX Coordinator, or decision-maker in the same matter.

_ _ _ _ _

Parent and Guardian Rights

Consistent with the applicable laws of the jurisdiction in which the school is located, a student’s parent or guardian must be permitted to exercise the rights granted to their child under this school’s policy, whether such rights involve requesting supportive measures, filing a formal complaint, or participating in a grievance process. A student’s parent or guardian must also be permitted to accompany the student to meetings, interviews, and hearings, if applicable, during a grievance process in order to exercise rights on behalf of the student. The student may have an advisor of choice who is a different person from the parent or guardian.

Understanding Victim’s Emotional Responses and the Issue of Secondary Victimization

While varying from victim to victim—developmentally, over time, and relative to frequency, intensity, and duration—students react to sexual harassment across a range of different social, emotional, and behavioral responses.

Indeed, summarizing across a number of studies (e.g., Hailes, Yu, Danese, & Fazel, 2019; National Women’s Law Center, 2012; Roskin-Frazee, 2023), some of the most common outcomes of child or adolescent sexual abuse include:

Psychological Impact

Emotional Distress: Victims often experience intense emotions such as fear, anxiety, shame, guilt, anger, and depression. These feelings can persist long after the assault.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Many victims develop PTSD, characterized by intrusive memories, nightmares, hypervigilance, and avoidance of reminders related to the trauma.

Dissociation: Some victims may dissociate during the assault, feeling detached from their own bodies or experiencing amnesia.

Flashbacks: Vivid and distressing memories of the assault can intrude into daily life.

Self-Blame: Victims may blame themselves for the assault or feel ashamed.

Self-Harm: Victims may begin to self-harm or self-mutilate either as a representation of their self-blame, or as coping mechanism to demonstrate that they have control over at least one part of their life.

Trust Issues: Trust in others may be shattered, leading to difficulties in forming new relationships.

Sexual Dysfunction: Victims may experience changes in sexual desire, arousal, or functioning.

Sleep Disturbances: Nightmares, insomnia, and disrupted sleep patterns are common.

_ _ _ _ _

Sociological Impact

Stigma and Social Isolation: Victims may face stigma, judgment, or disbelief from others. When adolescent victims are not believed, it exacerbates their trauma.

Relationship Challenges: Relationships with family, friends, and partners can be strained due to the emotional aftermath of the sexual abuse.

Educational and Occupational Disruptions: Victims may struggle academically or professionally due to trauma-related difficulties.

_ _ _ _ _

Long-Term Effects

Some victims experience long-lasting effects, including chronic anxiety, depression, and difficulty trusting others.

The impact of rape extends beyond the individual survivor to their families and communities.

_ _ _ _ _

Significantly, school staff and—especially—administrators need to understand these potential reactions because a victim’s behaviors and interactions may significantly change (as above) after the harassment, or even due to (or compounded by) the complaint and investigation process.

School staff and administrators also need to monitor how peers and others in the student body hear about, react to, and/or are affected by the harassment situation. . . as it may become known (and, not necessarily accurately) through different social channels.

Indeed, at times, the victim’s behavior may be inappropriate or even extreme—from a “disciplinary” perspective—even though it is a psychological reaction to the harassment or its aftermath.

All of this suggests that administrators need to involve their mental health professionals early on in this process. . . both relative to the students directly involved in the harassment, and those who are involved “on the periphery.”

While challenging, at times, administrators may need to respond more from a mental health perspective than a disciplinary perspective relative to victims’ behavior and interactions after a harassment event (be it a Title IX event or not) has occurred.

_ _ _ _ _

Secondary Victimization

Administrators and school staff also need to understand that how they respond to a sexual harassment allegation, correctly using—or not—the Title IX procedures, may separately impact the victim socially, emotionally, or behaviorally.

Indeed, one of the critical variables embedded in a sexual harassment situation for victims is the issue of “control.”

Many victims feel that they had no control over the sexual harassment event, and that they have little or no control over much of its aftermath.

Hence, they are trying to assert and regain some level of control over some parts of their lives.

When districts do not follow—or inaccurately or unfairly follow—the Title IX procedures, some victims feel a renewed or continued level of (for example) hopelessness, disrespect, or anger. This reinforces their lack of control over important facets of their lives, resulting in an emotional “vicious cycle.”

This cycle is called Secondary Victimization. . . which can also occur in how District and/or Law Enforcement staff handle sexual harassment complaints, investigations, hearings, or appeals.

Secondary Victimization:

Secondary victimization is victimization that occurs, not as a direct result of an original inappropriate, antisocial, unlawful, or criminal act, but through the response of individuals (like peers or others), representatives (like administrators acting on behalf of a district or school), and/or institutions (like law enforcement or the court system and its players) to the victim.

Secondary victimization is an indirect result of the primary assault that occurs through the responses of these individuals, representatives, and institutions to the victim. Types of secondary victimization include, for example, (a) victim blaming, shunning, rejection, or ridicule; (b) inappropriate behavior or language by medical personnel or others in organizations that interact with the victim post-assault; or (c) implicit or explicit biases reflected in a lack of objectivity with or towards the victim, or conscious or unconscious favoritism of the assailant.

Secondary victimization can also be called “post-crime victimization” or “double victimization.”

Critically, secondary victimization is another psychological reaction that school and district staff and administrators need to be aware of. While it may occur due to a poorly organized Title IX experience, it could occur at any point in time after a sexual harassment event due to other emotionally-triggering interactions.

Summary

The Title IX Fact Sheet from the U.S. Department of Education provides the following guidance:

Recognition of Sexual Harassment as Sex Discrimination

Sexual harassment under Title IX includes—dating violence, domestic violence, and stalking.

_ _ _ _ _

Protections for Survivors

Survivors are in the position of control to decide what happens after an incident of sexual harassment, including sexual assault, occurs.

Schools must respect a survivor’s decision to file, or not to file, a formal complaint and must offer supportive measures either way.

Schools must respond promptly in every instance by offering to provide supportive measures like class schedule adjustments.

Schools are forbidden from pressuring a survivor into filing or not filing a formal complaint or participating in a grievance process.

To protect younger students, K-12 schools must respond promptly when any school employee has notice of sexual harassment, including sexual assault.

If a survivor chooses to participate in a grievance process, the regulation protects survivors from inappropriately being asked about prior sexual history (also known as “rape shield” protections), and the survivor must not be required to divulge any medical, psychological, or similarly privileged records.

A survivor never has to come face-to-face with the accused during a hearing, and an accused is never allowed to personally ask questions of a survivor.

Survivors are protected against retaliation when they choose to report sexual misconduct or not, file a formal complaint or not, participate in a grievance process or not.

Survivors are protected against bullying or harassment throughout the grievance process.

_ _ _ _ _

Campus Processes and Procedures

The regulation provides students with a right to written notice of allegations, the right to an advocate, and the right to submit, examine, and challenge evidence.

All students have the right to a live hearing where advisors conduct cross-examination.

All students have the right to an impartial finding based on evidence using a standard of evidence—either the preponderance of evidence standard or the clear and convincing standard—that applies to all members of the school community, including faculty.

Schools must offer both parties an equal opportunity to appeal the finding.

The regulation gives schools flexibility to conduct Title IX investigations and hearings remotely.

_ _ _ _ _

Clearly, the best “Title IX” procedure here involves preventing sexual harassment from ever occurring. As such, in developmentally-appropriate ways across the age span, schools need to include discussions of sexual harassment—and overviews of the Title IX procedures—in their beginning-of-the-school-year school climate, expectations, and discipline discussions with students.

This should not be a “just give students the Student Handbook, and tell them to read and sign it” occasion.

_ _ _ _ _

Beyond this, it is important to recognize that the sexual harassment Title IX formal complaint process is very different from the Law Enforcement process.

The Title IX grievance process, importantly, provides students access to due process without being put through the machinations and unpredictability of the court system.

Moreover, the criteria to validate the Complainant’s allegation—and to receive relief, if verified—significantly differ relative to Title IX and the Court system. The Title IX process largely looks at sexual harassment from a disciplinary perspective (relative to the Respondent), and a student health, mental health, and wellness perspective (relative to the victim). The court system process aligns the alleged behavior with statutory and case law, and then focuses on punishment and compensation.

The former process is typically quicker, more likely to result in a definitive decision, and it is far more likely to be psycho-educationally meaningful to all parties.

_ _ _ _ _

We hope that this Blog has been both relevant and helpful to you, and we encourage you to review the resources cited above, and to share this piece with your colleagues.

While most schools are now on (or near) “summer vacation,” we know that some of you continue to work—analyzing and debriefing the past school year to prepare for the new one.

Know that, even during the summer, I am available to you and your team to discuss any of your “strategic planning” work. Our first conversation is free, and many districts and schools take the suggestions from our “first” conversation, and move “to the next level of excellence” on their own.

I hope to hear from you. . . or see you at the Model Schools Conference, June 23-26, 2024 in Orlando, FL where I will be making two presentations: “Building Strong Schools to Strengthen Student Outcomes: The Seven Sure Solutions,” and “Successful Federal Grant Writing 101: A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing U.S. Department of Education Grants that Get Funded.”

Best,