Delegating Duties and Decisions in a Shared Leadership School:

Avoiding Staff Reservations or Resentment

[To listen to a synopsis and analysis of this Blog on the “Improving Education Today: The Deep Dive” podcast on Spotify. . . hosted by popular AI Educators, Angela Jones and Davey Johnson: CLICK HERE for Angela and Davey’s Enlightening Discussion]

Dear Colleagues,

Effective delegation is critical to administrators’ success. Delegating properly can empower staff and give them leadership experiences and decision-making control, allowing them to exhibit agency over important stakes. Yet, our research shows that, if not done effectively and at the right time, staff can view delegated decision-making as a burden that they would prefer to avoid. Knowing when, when not, and how to delegate helps administrators navigate this process effectively without paying an interpersonal price.

Hayley Blunden and Mary Steffel (with minor modifications)

_ _ _ _ _

Introduction

When implementing a building-wide academic or school discipline, classroom management, and student engagement initiative, it is essential to work from a systemic, ecological, whole-school-improvement perspective. This is because classrooms’ academic/instructional and classroom management/student engagement processes are interdependent.

I have demonstrated this for over forty years in the field by asking educators three simple questions:

- Do you have students in your classrooms who are behaviorally acting out because of academic struggles?

- Do you have other students in your classrooms who are academically struggling because of social, emotional, or behavioral challenges?

- When you have an academically struggling student or a behaviorally challenging student, which is which based on why are they having these difficulties?

Consistently, the answer to the first two questions is, “Yes.”

The answer to the third question. . . after some thought and reflection on the interdependence of students’ academic and behavioral classroom performance. . . is:

“I don’t know. It could be an academic or social, emotional, behavioral problem. . . or both.”

And that’s the point.

Before schools implement school-wide academic initiatives, they must look at how their school’s current discipline, classroom management, and student engagement processes are impacting their students’ academic instruction, learning, and mastery. . . and how the new initiative might positively or adversely impact these same processes.

Similarly, before schools implement school discipline, classroom management, and student engagement initiatives, they must evaluate the impact of their existing academic program. . . and how the new initiative might positively or adversely impact these same processes.

_ _ _ _ _

For me, the strategic planning for any school initiative. . . indeed, for all school improvement activities. . . involves a shared, collaborative leadership structure and process.

And this shared leadership structure and process requires staff involvement, commitment, and productivity. . . and the delegation of certain duties and decisions by school administrators to school staff.

And there’s the rub.

How do administrators best delegate duties and decisions to school staff—to individuals, teams, grade levels, departments, committees, or everyone in the entire organization—so that they embrace them rather than (as in the quote above) “paying an interpersonal price” because they are seen as “burdens to avoid?”

In this Blog, we will describe (a) the essential structure and process in a shared, collaborative leadership school; (b) recent research reported by Hayley Blunden and Mary Steffel on how to effectively delegate duties and decisions to staff members; and (c) how to apply the two together.

Expanding on the Shared Leadership School

As emphasized above, there are two essential elements in a successful Shared Leadership School: (a) a formal and well-organized shared leadership structure, and (b) differentiated decision-making processes.

While virtually no administrator would question this, most districts and schools have a loose shared leadership structure (if they have one at all), and they use decision-making processes that vary—sometimes unpredictably—over time and across different situations.

Critically, the shared leadership structure should incorporate the science-to-practice components that (a) facilitate sound strategic planning and school improvement at the student, teacher, and classroom levels; and (b) result in successful and effective school and schooling outcomes.

The differentiated decision-making processes need to use research, experience, and common sense so that they can be implemented flexibly to adapt to specific student, staff, and school questions and needs.

_ _ _ _ _

The Shared Leadership School Structure

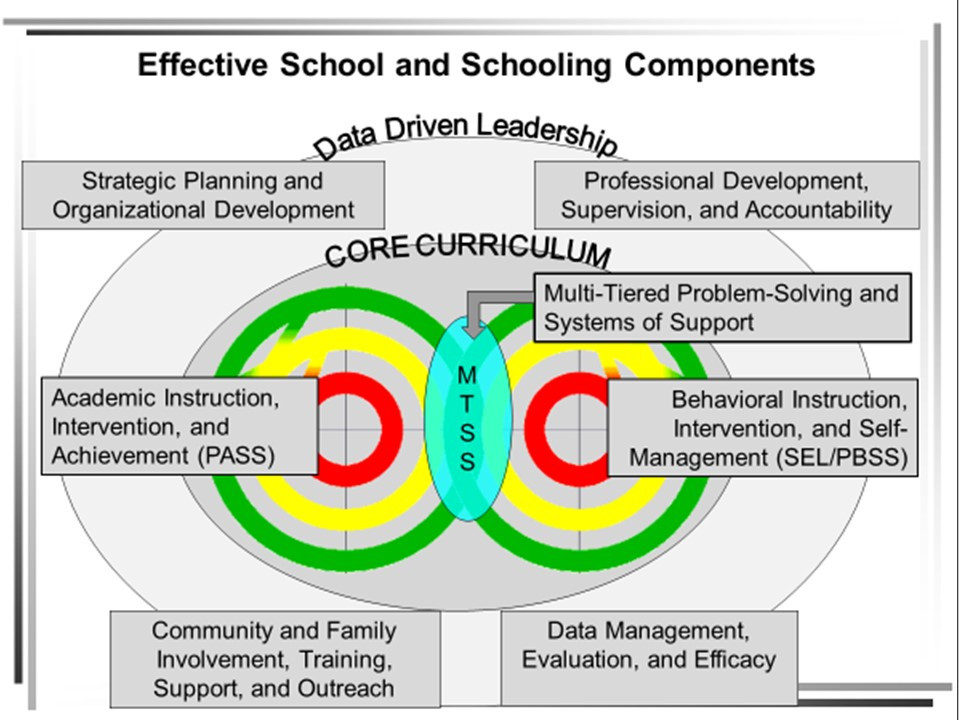

Based on long-standing science-to-practice studies, there are seven interdependent areas that help produce positive, sustained, and meaningful school and schooling outcomes (see Figure 1 below):

- Area 1. Strategic Planning and Organizational Analysis and Development

- Area 2. Multi-Tiered Problem-Solving and Systems of Support (MTSS)

- Area 3. Professional Development, Supervision, Coaching, and Accountability

- Area 4. Academic Instruction, Assessment, Intervention, and Achievement (Positive Academic Supports and Services—PASS)

- Area 5. Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Instruction, Assessment, Intervention, and Self-Management (Social-Emotional Learning/ Positive Behavioral Support System—SEL/PBSS)

- Area 6. Parent and Community Involvement, Training, Support, and Outreach

- Area 7. Data Management, Evaluation, and Efficacy

Figure 1.

_ _ _ _ _

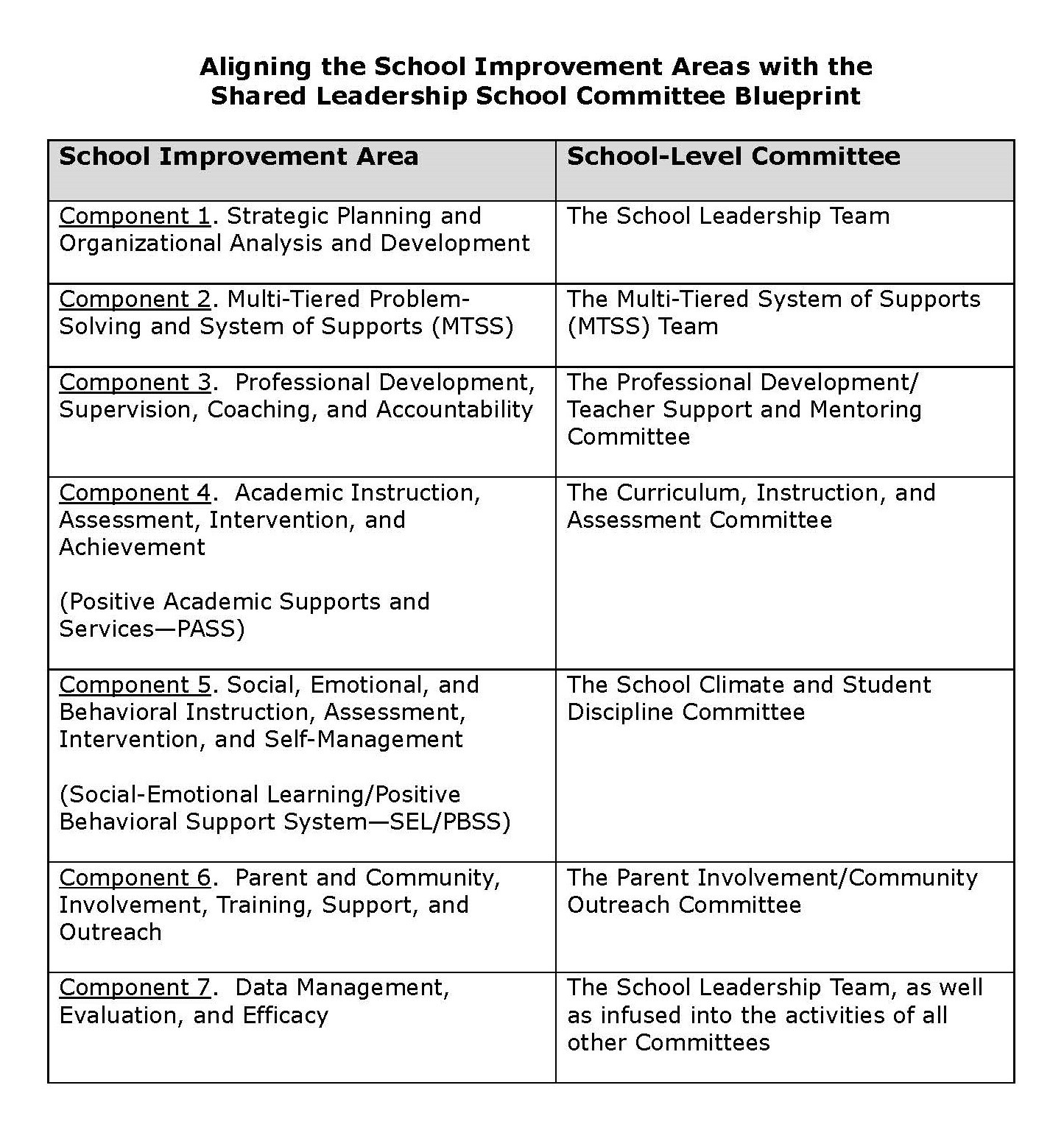

In a Shared Leadership School, the first six of these respective areas are overseen by specific school-level committees or teams (see Table 1 below). The last area is an embedded responsibility for all of these committees or teams.

(Critically, this shared leadership committee “blueprint” may be adapted given the size, needs, or challenges within a specific school. Moreover, we certainly recognize the presence and importance of other teams—for example, grade-level teams—that also exist in effective schools.)

Table 1.

Briefly describing these committees or teams:

Briefly describing these committees or teams:

Led by the School Principal, the School Leadership Team (SLT) is primarily responsible for overseeing activities related to the Strategic Planning and Organizational Analysis and Development component within the effective school and schooling model. Thus, it makes most of the site-based management and related organizational and fiscal decisions on behalf of the school, or recommends these to the administration. The SLT is ultimately responsible for planning (e.g., through the annual School Improvement Plan) and evaluating all school-level and student-specific outcomes.

Because the core of the SLT involves the Chairs or Co-Chairs of the other school-level committee, they report on their respective committee meetings and activities so that all SLT members are duly briefed and can coordinate and collaborate, as appropriate, across school committees, teams, and staff. All of this facilitates a seamless “bottom-up” (i.e., from individual staff to grade levels to school-level committees to SLT and administration) communication process, as well as a “top-down” (i.e., from the administration on down) process.

While the SLT is the oversight committee to which all other committees report, there still is a clear delineation between the mandated and district-designated responsibilities of the school’s administration and the shared leadership responsibilities of the SLT. In the former area, the SLT may be advisory to the school’s administration relative to certain administrative responsibilities, actions, and/or decisions where the administration must make final decisions. In the latter area, the SLT has many of its own decision-making responsibilities—still as agreed upon by the administration.

_ _ _ _ _

The MTSS—Multi-Tiered System of Supports Team is responsible for developing, implementing, and evaluating the continuum of services, supports, strategies, and interventions, and the data-based problem-solving process to address the academic and/or social, emotional, and behavioral needs of students who are not responding to effective general education instruction and classroom management.

The MTSS team is composed of the strongest academic and behavioral intervention specialists in and available to the school, and it is also often responsible for determining a student’s eligibility for more intensive special education services if strategic interventions, over time and consistent with IDEA, are not successful. As such, this multidisciplinary Team is largely staffed by related service and specialization professionals—including special education teachers, the school nurse, the School Principal, and relevant others.

Given all of this, this committee is largely responsible for the school and School Improvement Plan’s Problem Solving, Teaming, and Consultation Processes component and activities, but this committee’s activities clearly overlap with other committees, especially those focused on the school’s core academic instruction and social, emotional, and behavioral programming for all students.

_ _ _ _ _

The Professional Development/Teacher Support and Mentoring Committee oversees, facilitates, and evaluates the school’s professional development (PD), and formal and informal collegial supervision and support activities. These activities should help all staff feel professionally and personally connected to the school and its organizational, planning, instruction, and continuous improvement processes, and motivate them to interact instructionally and personally with students and each other at the highest levels of effectiveness.

With goals and outcomes connected to the School Improvement Plan, this committee helps to evaluate the short- and long-term implementation and outcomes of the school’s PD program, making recommendations to ensure that all PD initiatives (a) are delivered using appropriate adult learning approaches; and (b) implemented so that staff receive the depth of training, job-embedded practice, supervision and feedback, and time needed to be successful. Ultimately, this committee facilitates a process such that the information and knowledge provided during any PD training transfers into instructional skill and confidence over time, and that the school’s PD program and process collectively results in meaningful student outcomes.

_ _ _ _ _

The Professional Development/Teacher Support and Mentoring Committee also helps welcome and orient staff who are new to the building each year, coordinates the teacher mentoring program for teachers who are new to the profession, and guides others who have completed this induction process and are moving toward earning tenure or continuing appointments. In addition, this committee stays abreast of new pedagogical or technological advances in the field, periodically briefing the faculty on these new approaches and how they can improve the school and schooling process.

_ _ _ _ _

The Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment Committee looks at the most effective ways to teach and infuse the primary academic areas of literacy, mathematics, written/oral expression, and science to all students in the school throughout the instructional process and day. Meeting on at least a monthly basis with goals and outcomes connected to the School Improvement Plan, this committee also oversees the implementation of new and other existing district- and building-level curricula into the classroom such that they are most effectively taught to all students.

The membership of this committee includes representatives from every grade or instructional/ teaching team or level, including representatives from every intervention support or consultation group in the school and administrators. Many times, this Committee extends from the school-level up to the district level, and from the school-level down to the grade (or instructional team) level and individual teachers’ classrooms. As such, this “Committee” often is as differentiated as the curricula being taught in the school and, in large schools, it may have curriculum-specific subcommittees or other organizational arrangements, as needed, to facilitate the instruction and achievement of all students.

_ _ _ _ _

The School Climate and Student Discipline Committee is the building-level committee that oversees the school’s positive behavioral supports and interventions, school discipline, behavior management, and school safety processes and activities. Meeting on at least a monthly basis with goals and outcomes connected to the School Improvement Plan, this committee looks at the most effective ways to facilitate positive interpersonal, social problem solving, and conflict resolution skills and interactions across students and staff such that students feel connected to the school, engaged in classroom activities, and safe across the school’s common areas.

This Committee also addresses large-scale issues of teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, and physical aggression—working to prevent these situations across the student body, and responding to them with strategic or intensive interventions as needed. In addition, the Committee oversees crisis prevention for the school, and is prepared to intervene when crises occur. Finally, this Committee works to involve school support staff (e.g., custodians, cafeteria workers, secretaries, bus drivers) in its efforts, and it reaches out to parents and community agencies, and other community leaders in a collaborative effort to extend its activities to home and community.

_ _ _ _ _

The Parent Involvement/Community Outreach Committee is responsible for planning, implementing, and evaluating the school’s parent and community outreach goals and activities as written into the school’s annual School Improvement Plan. As such, based ongoing needs assessments of the school’s different parent and community groups and constituencies, and analyses of their resources, interest, and capacity, this committee focuses on (a) establishing and sustaining the collaborative approaches needed to address students’ academic and social, emotional, or behavioral needs in home or community settings, and (b) increasing the support, involvement, and leadership of parents, community agencies, and other organizations in accomplishing the school’s mission and goals.

Consisting of a representative cross-section of staff from within a school, this Committee collaborates with and supports its school’s PTA leaders and members. This Committee also collaborates with other community agencies and organizations, establishing partnerships with relevant businesses and foundations, and becoming, formally or informally, the public face and public relations unit for the school.

_ _ _ _ _

Three Embedded Committee Structure Principles

Critically, there are three embedded principles in establishing these teams or committees:

- All instructional and support staff are on at least one school-level committee;

- Every committee (except, perhaps, the Leadership Team) has representatives from every grade level (for elementary and middle schools) or departmental level (for some middle and all high schools); and

- Every committee (except the Leadership Team) is co-chaired by instructional and/or support staff, and these co-chairs form the core of the Leadership Team (administrators are ex officio to all committees)

This, once again, brings us back to the theme of this Blog. . . how to utilize these principles and establish these committees so that staff see them as advantageous—to themselves, their students, and the school’s culture and operation—and willingly participate and collaborate in the shared leadership process.

_ _ _ _ _

For those interested in a more detailed discussion in this specific area, we show how to implement a shared school leadership committee structure and process in our popular monograph:

Shared Leadership through School-Level Committees: Process, Preparation, and First-Year Action Plans

[CLICK HERE for More Information]

_ _ _ _ _

Moreover, we have discussed this committee blueprint in a previous Blog on staff development:

May 27, 2023

“Aligning the Seven Areas of Continuous School Improvement to Teacher Leadership and Advancement”

[CLICK HERE to Read this Blog]

_ _ _ _ _

Differentiating School Decision-Making Processes

In a Shared Leadership School, administrators differentiate among the common decisions that typically occur on a daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and annual basis.

They then (a) determine how these decisions will be made and by whom; (b) share and confirm this information with the School Leadership Team; and (c) discuss them with the entire staff—providing training in how effective committees and teams run, and how sound decisions are made. . . even when they are complex or controversial.

Focusing on the “how and the who” above, below are some ways that decisions are made by small and large groups in a school.

Critically, staff need to understand that the absence or abdication of making a needed decision is actually a decision to either maintain the status quo or to allow (or force) someone else to make the decision.

While this should not pressure staff into premature or rash decisions, it also should not routinely occur because, for example, (a) staff are unable to effectively discuss—or want to avoid making—complex or controversial decisions; or (b) a small number of staff are overtly or covertly “threatening” to undermine a majority decision.

Conversely, then, it is assumed that school and schooling decisions that are made will be supported and followed by all staff—even when they disagree with the decision, or it was not their first preference.

This is not to suggest that decision-making is dictatorial. Indeed, staff have the right to “agree to disagree,” express and document their concerns and apprehensions, and—in some cases—ask administrators to revisit a decision. In the latter case, decisions that are illegal, unethical, potentially unprofessional, or contrary to the common (student) good should be revisited. (Note that we are not discussing personnel decisions here.)

While the assumptions above are implicit and universal, they may still need to be discussed explicitly—in general or when specific decisions are “on the table”—by school groups, committees, or with the entire staff.

Different decisions in a Shared Leadership School:

- Command Decisions: Decisions that are made by school administrators, largely on their own or due to their authority or official roles or responsibilities in the school.

_ _ _ _ _

- Expert Decisions: Decisions that are approved by school administrators, but are made by (for example, educational, psychological, pedagogical, or legal) Experts who are working in the school or who have been consulted or researched by the administrators.

_ _ _ _ _

- Consultative Decisions: Decisions that are made by school administrators, after consulting with a within-school team, committee, grade level or department, or individual staff member—or someone outside the school. Administrators here can make their own decisions; they are not bound by the information provided during the consultation.

_ _ _ _ _

- Consensus Decisions: Decisions that are made by informally scanning or polling a group. . . where an apparent majority of the group agree with a specific direction or option. A consensus decision is as binding as one determined by a formal vote, and individuals should be allowed to request a formal vote and additional discussion if desired.

_ _ _ _ _

- Voting Decisions: These are decisions where a formal vote (e.g., by a show of hands or “secret” ballot) is taken on a decision or a “motion on the floor” (if, for example, the school uses Robert’s Rules of Order for decision-making).

Administrators, the School Leadership Team, or school staff may decide—in advance—that some decisions will require a simple majority (i.e., 51% of the vote) to “pass,” while other decisions will require a “super-majority” (i.e., 60% or 67% of the vote). In very rare cases, a unanimous (100%) vote standard may be used.

When multiple options (e.g., selecting one curriculum from five options) are being weighed at the same time, the “standard for winning” should be determined or agreed-upon in advance. This, for example, may involve (a) an absolute vote—where the option with the most votes (regardless of the number or percentage) “wins;” (b) a weighted vote—where the options are given points based on each staff member’s ranked preferences, and the most-preferred option wins; or (c) a “drop-out” vote—where there are a series of votes, and the option with the lowest score in each “round” is dropped-out.

_ _ _ _ _

- Minority Decisions: This decision typically is not planned, and should be avoided. It occurs when one individual or a small (but, for example, vocal, powerful, or regarded) number of individuals vote counter to the majority, and/or voice a dissent after the votes and decision have been announced. At this point, in deference to these individuals, the rest of the group acquiesce to their dissent and vacate the vote.

If this “if I don’t get my way, I’ll take the ball and go home” tactic or strategy is allowed, then the “minority” could be empowered, and the integrity of a school’s decision-making process will be weakened or damaged.

The “antidote” here is to (a) reassert the expectation that the everyone will respect and support all final decisions; (b) review, in advance, the voting procedure—along with the standard of winning; and (c) ensure that the formal vote does not begin until sufficient discussion has occurred.

_ _ _ _ _

When schools effectively implement and consistently sustain these two essential Shared Leadership School components—a formal and well-organized shared leadership structure, and differentiated decision-making processes—they create a culture and mindset where staff recognize that their involvement in school committees and relevant school decisions is:

- A relevant part of their professional role and responsibility;

- Beneficial to their professional and personal well-being and success; and

- An important contribution to the success of the school and its student body.

Research: How to Strategically Delegate Duties and Decision-Making

Blunden and Steffel, in a September 10, 2024 Harvard Business Review article, completed a progressive series of controlled experiments and surveys with 2,478 participants from across the United States.

They found that:

Delegating decision-making responsibilities, compared with asking employees for advice and maintaining decision-making responsibility, had significant interpersonal costs for delegators. But we also found material ways that managers can alter how and when they delegate decisions, so that employees feel empowered rather than burdened.

The results of the first set of these systematically-completed studies indicated:

- Study 1. When recalling past incidents with their supervisors, staff who were delegated a task versus asked for their advice were less willing to help the same individual with a future decision–-regardless of the positive or negative outcome of the decision.

_ _ _ _ _

- Study 2. As part of a research study, when asked to decide between two administrative candidates during an on-line chat, staff were more likely to hire the individual who asked their advice during an interview challenge than the candidate delegated a choice to them.

_ _ _ _ _

- Study 3. As part of the next research study, when asked whether they wanted to continue working with their team leader during an online team chat, staff who had been delegated to during the chat were more likely to end their relationship with the leader when compared to staff whose leader asked for their advice.

_ _ _ _ _

Blunden and Steffel concluded:

It turns out that the people in our studies thought being asked to make a decision was less fair than being asked for advice, and that this sense of unfairness made them view delegators more negatively. It may seem unfair when someone asks a colleague to take on decision responsibility—and its potential burdens—when the colleague views that responsibility as rightfully the requester’s to shoulder.

_ _ _ _ _

Given these research outcomes, Blunden and Steffel next investigated the ways that supervisors or managers could delegate tasks or decisions without seeming unfair.

- Study 4. In a controlled experiment, 578 participants were asked to imagine being asked by a supervisor either to make a decision or to give advice regarding laying off colleagues (a negative outcome) or awarding colleagues a bonus (a positive one). The participants were then asked to indicate how fair they felt the supervisor making the request was.

For those asked to make a layoff decision, Blunden and Steffel again found that participants whose supervisors delegated the decision to them (versus asking for their advice) were less willingness to provide help with future decisions. Yet, when asked to award colleagues’ bonuses, there was no difference in the willingness to help supervisors with future decisions between the participants delegated this decision versus simply asked for their advice.

In their follow-up analyses, the researchers found that participants told to make a positive outcome decision (i.e., awarding a bonus) felt that this was fairer than being told to make a negative outcome decision (i.e., laying someone off).

_ _ _ _ _

- Study 5. Critically, the results of next study demonstrated that supervisors were not rated down when they asked staff to make decisions that were relevant to them and that were consistent with their work roles and functions. In this situation, staff saw the delegation of the decision to them as “fair.”

_ _ _ _ _

Blunden and Steffel summarized all of their studies’ results:

When the decision outcome has a high potential to have negative consequences, is outside of the employee’s scope of responsibilities, and primarily affects others, there are likely to be interpersonal costs of decision delegation, and managers looking to utilize their employees’ knowledge should ask for advice instead. When these elements are reversed, transferring decision responsibility is likely to be less interpersonally costly and might provide employees a better venue to test out their decision-making skills.

Our work suggests that those seeking to delegate decisions may benefit from pursuing strategies that make their requests seem fairer. For example, delegators could consider framing a decision within the scope of their colleague’s responsibilities or could articulate how they will take active responsibility for any fallout from an employee’s choice.

Implications for Administrators in a Shared Leadership School

Adapting the research summary paragraph immediately above into “action steps,” administrators would be well-advised to delegate duties and decisions to their staff that:

- Are consistent with their existing (or imminent) roles, responsibilities, and job descriptions;

- Bring their knowledge, skills, and competence to the “next level” of excellence and efficacy;

- Have a high potential to contribute to and positively extend their success and impact on students and other colleagues;

- Have a high potential to identify and eliminate existing ineffective strategies and/or time-consuming or counter-productive tasks; and

- Are fair and equitable with respect to what other staff/colleagues are being asked to contribute.

All of these should be accomplished by asking staff to help build the school’s Shared Leadership system, by actively soliciting and judiciously using staff advice and recommendations, and by ensuring that new responsibilities are counter-balanced with the release of existing ones.

Moreover, relative to any new duties or decision-making responsibilities, administrators should publicly commit to and consistently demonstrate that they “have their staff’s back.” While mis-steps or mistakes may occur as staff get used to new delegated roles or decision-making and leadership responsibilities, administrators need to focus on how to succeed “next time” through analysis, adjustment, advancement, and improvement.

_ _ _ _ _

As noted above, when schools effectively implement a well-organized shared leadership structure, and staff learn and apply sound and differentiated decision-making processes, staff embrace their new shared leadership roles and responsibilities because they enhance their professional and personal success, and that of their students, colleagues, and school.

Indeed, through experience, they recognize that:

- Schools and districts are stronger when experienced and talented people work together on shared short- and long-term goals, actions, activities, and accomplishments; and

- Having the responsibility to make some school and schooling decisions gives them an active voice in how the school is run, as well as what their future expectations, assignments, roles, and contributions might be.

Ultimately, this is a win-win for both administrators and staff.

When new roles and decision-making responsibilities are communicated and shared successfully by administrators, they have more resources and people contributing to all of the tasks that go into running a successful school.

When administrators work as collaborative colleagues with staff, staff feel more trusted, involved, informed, and aware of the complexities of a school and the job of their administrators.

Summary

This Blog discussed the significant benefits of having a Shared Leadership structure and process in every school across the country. The structure was defined by the seven research-to-practice components evident in all successful schools. These were aligned to six school-level committees—each responsible for their part of the school success operation.

The process was defined by describing the different ways to make school and schooling decisions. This is critical as successful Shared Leadership occurs when staff, who serve on committees, learn how to make decisions within those committees—and elsewhere in the school—on their own and on behalf of their colleagues.

Knowing that some staff may initially be uncomfortable in a Shared Leadership School, we summarized the research in a recent Harvard Business Review article by Blunden and Steffel titled, “How to Delegate Decision-Making Strategically.”

This culminated in recommendations on how school administrators can best delegate duties and decisions to school staff so that they embrace their shared leadership responsibilities—rather than seeing them as unwanted or burdensome, and their administrators as unfair or insensitive.

_ _ _ _ _

I hope that this Blog has either reinforced your current approaches to shared leadership in the settings where you work, or has opened a “new door” to you as to its benefits and features.

As we near the mid-point of the school year, know that I continue to work on-site and virtually with schools and districts across the country—not just in strategic planning and the implementation of shared leadership approaches. . . but also in the areas of:

- Enhancing school climate and student engagement;

- Teaching students interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional awareness, control, communication, and coping skills;

- Implementing effective Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS); and

- Implementing effective Tier 2 and Tier 3 services, supports, and interventions for students with challenging behavior.

If you and your team would like to discuss any of these areas with me, please feel free to e-mail or call me, and we can schedule a free first consultation session.

I hope to hear from you soon.

Best,