A New Center for Civil Rights Remedies Report Concludes (again) that Schools are NOT Closing the Minority and Exceptional Student Discipline Gap

Reports say that the Chicago Public Schools’ Restorative Practice Policies and Approaches Have Decreased the “Numbers,” but Increased “Havoc and Lawlessness”

Dear Colleagues,

Steve Tobak once said,

“Great innovators don’t see different things. . . they see the same things differently.”

Today’s discussion is about the continuing problem, in schools across the country, relative to the disproportionate number of poor, minority, and special education students who are suspended or expelled from school (or sent to the principal’s office, or put into alternative school programs) due to their “discipline problems.”

More specifically, I will first highlight a report published last month by The Center for Civil Rights Remedies that again documents, in great detail, the statement above. This will be followed with comments on a related February 25th article in the Chicago Tribune by Juan Perez Jr. Mr. Perez reported that the Chicago Public School District’s changes, last year, to its Student Code of Conduct, its training in classroom management and use of restorative practices, and its $15 million investment on nearly five dozen vendors to work on school discipline issues with teachers and students has resulted in- - according to one teacher- - “lawlessness.”

In the end, I will outline the student, staff, and school approaches needed to increase students’ interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills, decrease their social, emotional, and behavioral challenges, and thereby close the school suspension disproportionality gap.

Now applying Tobak’s quote. . . It is indisputable that poor, minority, and special education students are being disproportionately suspended or expelled from school for “behavioral difficulties” that inconsistently range from minor infractions to major offenses. But it is interesting that different “innovators” are “seeing the same things differently,” and responding (often inappropriately) from somewhat singular, “one size fits all” perspectives.

For example:

- Policymakers often see the problem as needing changes in policy- - for example, changing an inappropriate zero tolerance policy to a naïve restorative justice policy

- District administrators often see the problem as needing changes in practices- - that is, adding more training (for example, in classroom management) to increase the competence of teachers and others to prevent and/or respond to students’ behavioral challenges

- School administrators often see the problem as needing changes in personnel- - that is, adding more people (for example, untrained paraprofessional “behavior interventionists” or, as in Chicago, “restorative practice coaches”) to increase the number of staff available to “manage” disruptive students

- And, student advocates often see the problem as needing changes in perspective- - focusing on changing how different students are perceived- - along a continuum that actually ranges from some staff’s unintentional or misinformed misperceptions, to other staff’s intentional or ignorant biases or racial prejudices.

In actuality, all of these changes are potentially needed. . . but they are often applied randomly, in the absence of sound data-based analyses, as top-down mandates, without the necessary training and resources, and in isolated and (once again) singular and “one size fits all” ways. It’s almost as if we are throwing spaghetti at the wall- - concluding that it’s done when it sticks.

Disproportionality is a multi-factored student, staff, school, and community issue. In order to solve it, we need to “work the problem,” and not just “change the numbers.”

A New National Report on Disproportionate School Suspensions

Last month, The Center for Civil Rights Project published a new report (Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?) analyzing the school suspension data from our nation’s schools during the 2011-2012 school year.

During this school year:

- Nearly 3.5 million public school students were suspended out of school at least once

- 1.55 million students were suspended at least twice

- Suspension rates differed significantly across schools, districts, states, and time- - but high-suspension districts suspended more than 1 out of every 10 elementary school students, and 1 out of every 4 secondary students

- With the average suspension lasting 3.5 days, nearly 18 million days of instruction were lost by our nation’s students during this single school year

But most importantly, according to the Report:

- The biggest difference in suspension rates related to how specific school and district administrators approached and implemented their disciplinary policies.

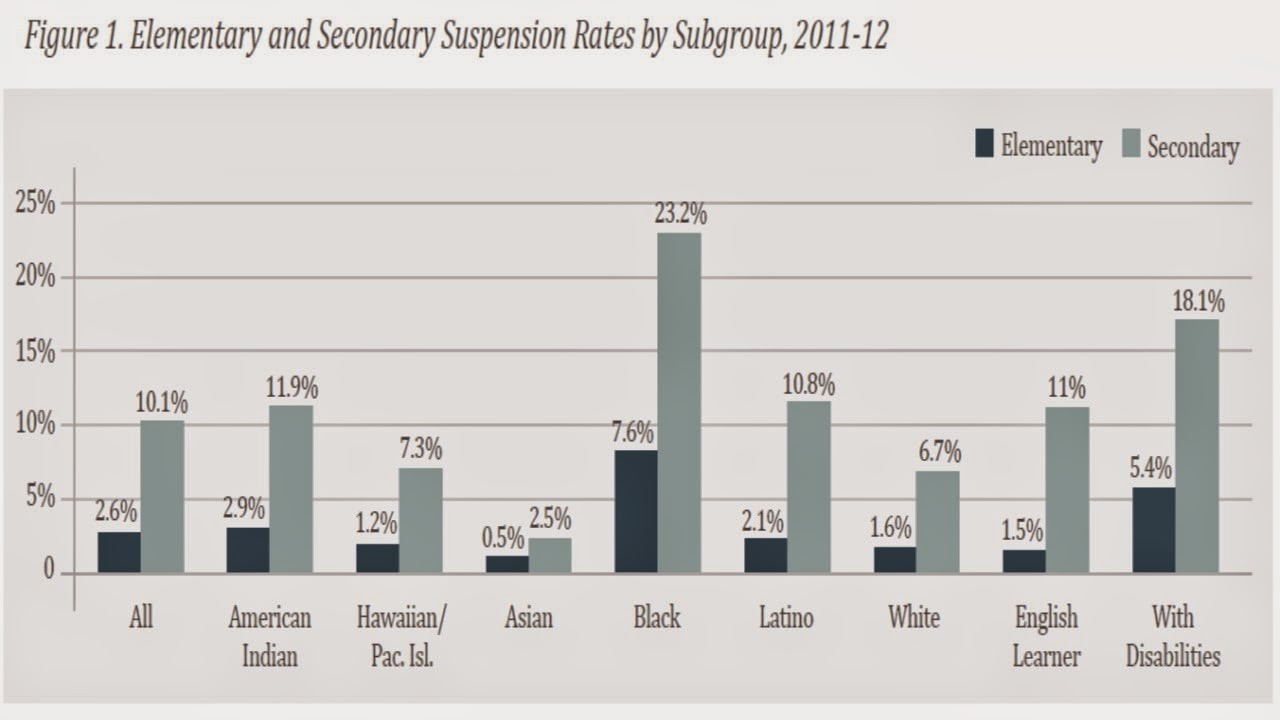

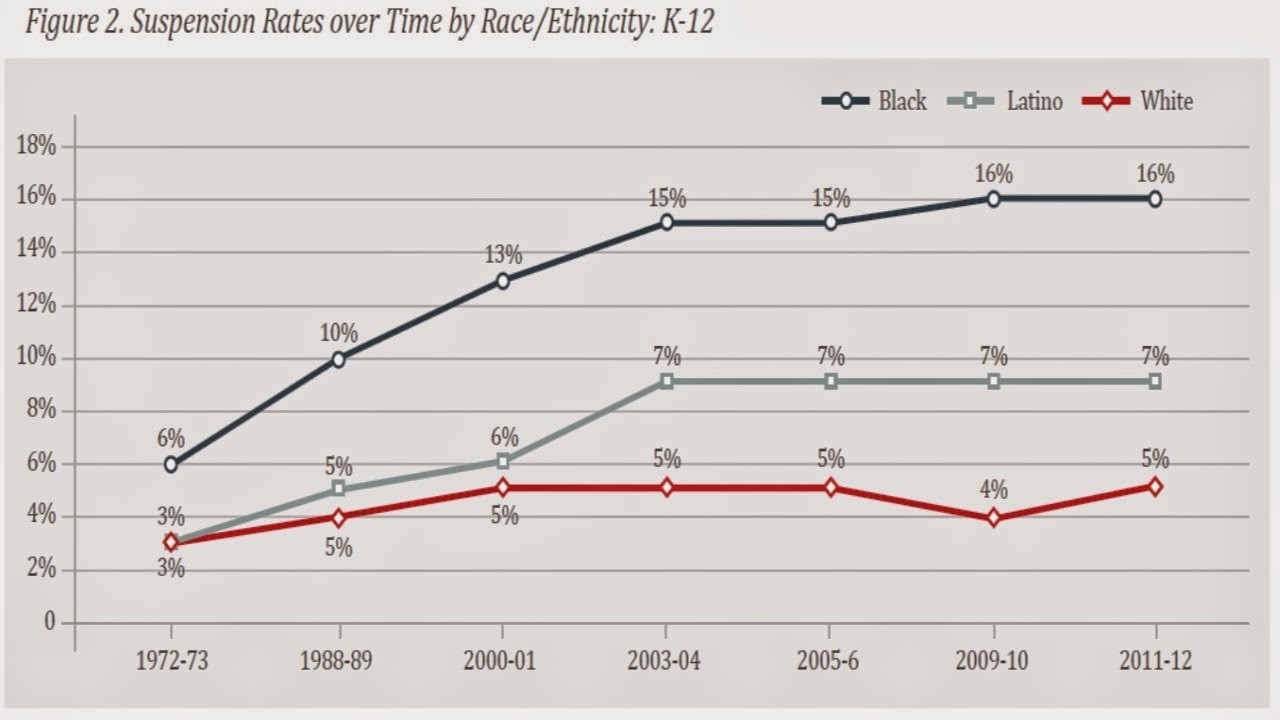

More Data. Relative to students’ racial, English Language Learner, and special education background or status, the Report provided the following suspension data (see figures below) from the 2011-2012 school year, as well as historically since 1972.

Finally, while the Report identified a number of large city school districts that had “most improved” their suspension rates over time, it appeared that the “improvement” was due more to policy than practice. Indeed, many of these districts did not comprehensively change the systemic practices of staff and administrators in their schools. . . they did not increase the number of advanced skill mental and behavioral health and intervention professionals. . . they did not engage in staff and community outreach programs to increase the understanding and sensitivity to individual student differences. . . and they did not embed their school-based approaches into community-wide social, economic, political, and grass-roots initiatives.

A Chicago Public Schools Case Study

Chicago provides a telling case study of what happens when policies designed to “change the numbers,” are not complemented by strategic, differentiated practices designed to “change the people.”

In his February 25th Chicago Tribune article, Juan Perez Jr. reported that the Chicago Public School District’s changes, last year, to its Student Code of Conduct, its training in classroom management and use of restorative practices, and its $15 million investment on nearly five dozen vendors to work on school discipline issues with teachers and students has resulted in- - according to one teacher- - “lawlessness.”

Among the biggest problems cited in the article were the following:

- Teachers say they have not been given resources to work with the revised Student

- Code of Conduct

- Some schools do not have behavioral specialists on staff to intervene with students, nor resources to train teachers on discipline practices that address students’ underlying needs

- Approaches have shifted too far such that some staff say there are no consequences, inconsistent enforcement, and/or little collaboration among in-school staff, administrators, and in-school staff from the outside vendors

- District-provided training in areas like restorative practices and classroom management are not provided to entire schools

- Resources- - like "restorative practices coaches" and behavioral health teams are allocated to schools based on (high discipline incident) behavioral data

- Restorative practice coaches are only in the schools on a weekly basis- - regardless of need

- The new conduct code places stronger limits on the use of suspensions and seeks to avoid consequences that would pull a student from classes or the school building

- Prekindergarten through second-grade students can't receive an in-school or out-of-school suspension without approval of a district supervisor

In the end, while the number of in-school and out-of-school suspensions in the District declined between the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, racial disparities remained. But once again, the numbers decreased due to the policies that discouraged and/or controlled educators’ use of suspension, not due to increases in students with more appropriate behavior, and decreases in students presenting frequent or significant behavioral challenges.

Reality Check

To set the record straight, please understand that I believe that:

- It is critically important to decrease the number of students being suspended from our schools nationwide, and to eliminate suspensions that are arbitrary, unnecessary, steeped in prejudice, and that do not match the intensity of the offense. (We just need to do it the right way.)

- Legitimate decreases in student suspensions and even discipline referrals to the principal’s office do not always result in simultaneous increases in positive school and classroom climates, student engagement, and prosocial student behavior. (While we may successfully decrease the intensity of students’ challenging behavior- - such that they no longer need office referrals- - that does not mean that they are engaged and learning in their classrooms.)

- * Suspensions are administrative responses, and they rarely result in decreasing or eliminating students’ future inappropriate behavior, while simultaneously increasing their appropriate behavior. (In other words, without interventions that change students’ behaviors, the student returns from the suspension with the same problem.)

- * Some teacher referrals to the principal’s office and some administrative suspensions are arbitrary, capricious, and mean-spirited on one end; or due to a lack of student sensitivity (e.g., to cultural or disability issues), knowledge, understanding, and skill on the other end. (Thus, the root cause of “disproportionality” here is the adults. . . and the adults must be changed if the disproportionality is going to be changed.)

- Restorative Justice programs- - if implemented with appropriate integrity and intensity- - are useful programs. . . but only when they are matched to the students who will most benefit from those programs (based on analyses that confirm the underlying reasons for a student’s challenging behavior).

- Ultimately, schools need to focus on teaching and reinforcing students’ interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and emotional coping skills; while also providing the assessment and intervention services, supports, strategies, and programs that the most challenging students need to address their inappropriate behavior. (Without school-wide prosocial skill instruction programs and approaches that motivate students to “make good choices,” we will never know how many challenging student behaviors we can prevent.)

Understanding Students’ Inappropriate Behavior

When students demonstrate social, emotional, or behavioral challenges, we need to work together to figure out why. Sometimes this can be done by an individual teacher. . . sometimes this is accomplished by a grade-level (or instructional) team working together. . . and sometimes this requires a school-level multidisciplinary early intervention team (like a Student Assistance Team, RtI Team, Student Services Team, or the equivalent).

Critically, though, everyone in the school needs to be trained in the same problem-solving process that helps to collect and analyze the information and data that determine the underlying reasons for students’ (academic and) inappropriate behavior. Once these underlying reasons are known, specific services, supports, strategies, and programs can be ascertained- - although this means that schools need to have professionals with extensive knowledge in classroom and other social, emotional, and behavioral interventions (so that problem analysis results are linked with the best problem solution approaches).

Some of the primary reasons why students demonstrate social, emotional, or behavioral problems in the classroom include:

- There are (known or undiagnosed) biological, physiological, biochemical, neurological, or other physically- or medically-related conditions or factors that are unknown, undiagnosed, untreated, or unaccounted for.

- They do not have positive relationships with teachers and/or peers in the school, and/or the school or classroom climate is so negative (or negative for them) that it is toxic.

- They are either academically frustrated (thus, they emotionally act out) or academically unsuccessful (thus, they are behaviorally motivated to escape further failure and frustration).

- Their teachers do not have effective classroom management skills, and/or the teachers at their grade or instructional levels do not have consistent classroom management approaches.

- They have not learned how to demonstrate and apply effective interpersonal, social problem-solving, conflict prevention and resolution, and/or emotional coping skills to specific (school-based or home-based) situations in their lives.

- They do not have the skills or motivation to work with peers- - for example, in the cooperative or project-based learning groups that are more prevalent in today’s classrooms.

- Meaningful incentives (to motivate appropriate behavior) or consequences (to discourage future inappropriate behavior) are not (consistently) present.

- They are not held accountable for appropriate behavior by, for example, requiring them (a) to apologize for and correct the results of their inappropriate behavior; and (b) role play, practice, or demonstrate the appropriate behavior that they should have done originally.

- Their behavior is due to past inconsistency-- across people, settings, situations, or other circumstances. For example, when teachers’ classroom management is inconsistent, some students will manipulate different situations to see how much they can "get away with." Or, when peers reinforce inappropriate student behavior while the adults are reinforcing appropriate behavior, students will often behave inappropriately because they value their peers more than the adults in the school.

- They are experiencing extenuating, traumatic, or crisis-related circumstances outside of school, and they need emotional support (sometimes including mental health) to cope with these situations and be more successful at school.

Critically, if we do not know the problem(s), we will never identify and implement the solution(s).

To expand on some of the reasons underlying students’ challenging behavior, feel free to watch the webinar below that I presented a few years ago to a national audience:

Changing Students’ Inappropriate Behavior

Finally, as noted earlier, many student problems can be prevented by implementing a scientifically-based school discipline, classroom management, and student self-management system. Based on our 30 years of evidence-based work in this area- - and implementation in thousands of schools in every state across the country, this system has the following interdependent components:

- *Staff, Student, and Parent Relationships that establish Positive School and Classroom Climates

- Explicit Classroom and Common School Area Expectations supported by Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Skill/Self-Management Instruction (that are embedded in preschool through high school "Health, Mental Health, and Wellness" activities)

- School-wide and Classroom Behavioral Accountability systems that include Motivational Approaches reinforcing "Good Choice" behavior

- Consistency--in the classroom, across classrooms, and across staff, time, settings, and situations

- Applications of the above across all Settings in the school, and relative to the Peer Group interactions (specifically targeting teasing, taunting, bullying, harassment, hazing, and physical aggression)

For more information about these components, please feel free to watch this short, ten-minute overview.

Summary

It is frustrating for everyone when concerted, well-intended efforts to address major school problems are unsuccessful. Moreover, when these problems get worse despite efforts that actually invest the right amount of time, funds, personnel, and other resources, the frustration often morphs into hopelessness and despair, or blaming and anger. . . along with a more refined resistance to future efforts.

Disproportionality. . . whether related to student discipline, placements into special education, access to effective teachers, equal educational opportunities, or civil rights. . . has existed throughout my professional career (and before). I don’t profess to possess “the silver bullet.” But I do know that our schools are not succeeding by simply changing policies, and throwing “one size fits all” programs at our practices. More importantly, I also know that success can occur by integrating and focusing our policies, practices, personnel, and perspectives on both enhancing the skills and strengths of our students, staff, schools, and communities, and addressing the multi-faceted reasons underlying this important issue.

As always, I hope that some of the ideas above resonate with you. . . or, at least, provoke some deep thinking. Feel free to contact me if you would like to reflect on these thoughts or discuss them in greater detail. Have a GREAT week !!!

Best,

Howie